Forensic Psychology For Dummies (67 page)

Read Forensic Psychology For Dummies Online

Authors: David Canter

Terrorism

Many crimes are committed by people who claim they’re fighting for a cause, which makes it very difficult to define acts of terrorism except in relation to what the perpetrators claim as the purpose of those actions. This is rather different from all other considerations of crime in which the actions themselves define the crime rather than the proposed reasons for those actions.

The aim of terrorism

The central idea of terrorism was articulated clearly in the 19th century by anarchists as ‘Propaganda of the Deed’. In other words, what’s crucial is the way in which their actions are interpreted (their symbolic meaning) instead of any direct impact on the functioning of society. The intention is to generate a violent reaction from the state so that mayhem ensues. Most governments these days are aware of this intention and deal with terrorist atrocities cautiously, so as not to provoke further reactions from people who may get caught in a vicious governmental response to terrorism, and so support the terrorists’ cause.

When considering terrorists as criminals who claim to be using robbery, murder or fraud to further political or ideological objectives, forensic psychologists can reflect on the same differences in styles that I describe earlier in this section for other crimes. For example, some terrorist groups are extremely confrontational, while others try only to attack targets that they regard as legitimate and some even try to avoid loss of life.

From a forensic psychology point of view, the important matters to establish are the details of what individual terrorists are doing and to understand their personal narratives (something I describe in the earlier section ‘Hearing the stories people tell themselves: Criminal narratives’), instead of being seduced by the rhetorical propaganda of their leaders.

Organised crime

Terrorist groups are the most obvious examples of organised criminals. They have a network of contacts that work together in a co-ordinated way to carry out crimes. But don’t fall into the trap of thinking that all criminal networks have similar strict hierarchies and structures; in fact, growing evidence suggests that not even terrorist groups are as tidily organised as is often assumed.

Maintaining an illegal organisation is rather difficult. Everything has to be secret and no one can be trusted unless they’re close family members or part of a powerfully coercive subculture, such as the Chinese Triads. As a consequence, the notorious criminal organisations such as the Mafia are a rarity among criminal networks, and even they’re not as tightly structured as the movies would have you believe.

The idea that illegal organisations have the same sort of structure as a legal one, with a chief executive, a board of directors, managers or departments, and clear lines of command is very misleading. They tend to be very volatile groupings drawing on different mixes of individuals for different crimes. The individuals involved have all the variations in their personality and styles that I discuss throughout this chapter. Consequently, the actions that occur in a crime known to be part of a particular criminal network, tell you something about the individuals carrying out that crime.

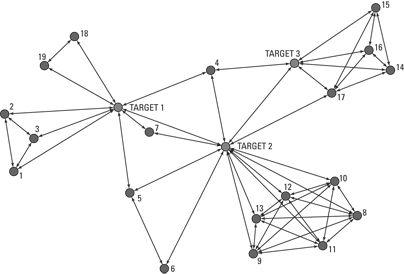

One interesting way of studying criminal networks is to look at who’s in contact with whom and to represent the result as a network chart (as shown in Figure 6-3). This approach allows investigators to identify the key individuals and cliques as well as determining who’s on the periphery of the network and so may be most open to informing to the police. Investigative psychologists can also establish the coherence of the network and how tight and interconnected it is to help determine its vulnerability to police interference.

For the example in Figure 6-3, the three target individuals provide the basis for a loosely knit gang that incorporates 19 people in total. Putting these three people out of action, say by imprisonment, would drastically reduce the network’s ability to function.

Investigative psychologists can also provide inferences about the characteristics of those involved in terrorist attacks in much the same way they can for any other crime. This can be particularly helpful in indentifying who in a terrorist group may be least committed to the terrorist cause and so may be willing to withdraw from the group and help the police.

Figure 6-3:

Illustration of a network of associates in a criminal gang. The light grey circles named Targets 1, 2 and 3 are well known prolific offenders. The lines join them to other individuals with whom they have been arrested.

Questioning Whether This Chapter Should be Published

One question I’m often asked is whether I’m giving too much of the game away by publishing accounts of how investigative psychology works. I still remember the row I had with a government official who said that publishing would just make criminals more savvy and difficult to catch. In reply, I asked her whether she’d have kept the potential use of fingerprints to solve crimes a secret if she could. Without hesitation, she said ‘yes!’.

I disagree with her for many reasons, but a main one is that in a democratic society it’s essential that no group has secret control of information that can be used to entrap others. Another reason is that secret science is inevitably bad science: if people disagree with what I write in this book, they can test their ideas and mine, show which are correct and allow everyone to benefit from the published results.

Perhaps the most important reason, though, is that crime grows out of criminals’ lack of awareness and insight into the implications and consequences of what they’re doing. When informed, criminals can change their activities. For example, out of the blue I got a letter from a prisoner in a South African prison who’d read my book

Criminal Shadows

(on which I draw throughout this book). This man had a long history of violence in and out of prison. He wrote that when he read my book he realised that he’d always thought of himself as a tragic victim and that that was inappropriate. Having gained that insight, he was now on the road to a productive, violence-free life.

Chapter 7

Understanding Victims of Crime and Their Experiences

In This Chapter

Discovering the victims of crime

Understanding the effects of crime

Assessing and helping victims

Assessing and helping victims

All too often in writing about crime – in fact and in fiction – the focus is on the criminal. Open any of the thousands of academic books about crime and you very rarely find a section on the victims and how to help them. Similarly, crime fiction nearly always focuses on the villain and catching him: the consequences of his actions for the victims and their families are rarely mentioned (unless the plot has a vengeful hero seeking retribution).

Over the last few years some experts have started to redress this imbalance by considering the consequences of being a victim and how to help those who experience crimes. Although forensic psychologists are often part of these considerations there are many other professional groups they may work with. These include criminologists, psychotherapists, psychiatrists, police officers and social workers, all of whom bring their own particular perspectives to bear on helping victims. These groups draw on the insights from forensic psychology, that I describe in this chapter, whether they have a professional forensic psychologist who’s part of their team and who has qualified as I describe in chapter 18, or not. This study of victims is known as

victimology,

and covers issues such as who becomes a victim and the resulting social and political implications, while also examining the legal processes that are in place to assist victims.

In general in this chapter I write about victims of crimes. But the experiences of victims of accidents overlap with these. If you have the great misfortune to be knocked down by a car the police will probably assume that it was a crime and the driver will be charged with dangerous driving or something similar. You will be appropriately angry at what you have suffered and if you are very unlucky you may experience some trauma similar to that experienced by people who are knocked down by a robber who steals their belongings. So there is no simple distinction between victims of crimes and victims of accidents. Therefore in some parts of this chapter I comment on the forensic psychology of accident victims as well as focussing mainly on crime victims.

In my opinion, however, too few of these studies deal directly with the experiences of victims and the psychological assistance they may need. In this chapter, I focus on the typical victims of crime and the impact on them of suffering from the acts of criminals. This aids understanding of what victims suffer, which is crucial for all the professional groups who seek to help them.

When I identify what typifies people who are victims of crime, of course I’m in no way blaming them for what they suffer. My hope is that by understanding their vulnerabilities the many different professions who help victims (as well as society in general) can do more to assist them and reduce crime.

Suffering at the Hands of Criminals: Who Become Victims of Crime?

Determining with accuracy how many crimes take place or who’s most likely to be a victim isn’t easy, mainly because not all crimes are reported to the police and the way in which reported crimes are recorded varies considerably from one law enforcement area to another. For example, the police may record some criminal acts that the public would see as serious, in such a way that they go into a category of minor offences.

Experts believe that only two sorts of crime are always reported to the police and so reasonably accurate figures are available only for the following:

Murder:

because that’s a crime hard to avoid if a body is found.

Car theft:

because the owner wants the insurance money and usually does have insurance because of legal requirements.

To get more accurate figures, therefore, many countries carry out crime surveys in which a carefully selected sample of the population is asked to indicate in confidence whether they’ve experienced any crimes in the previous year. These surveys invariably show a much larger number of crimes than are officially recorded, and researchers estimate that on average only about half of all crimes find their way into official records. Crime surveys pick up on otherwise unreported crimes, such as less serious crimes and criminal acts in areas where people don’t see any point in reporting them because they believe that nothing is going to be done about it. These surveys therefore help forensic psychologists to get a better picture of what crimes actually occur and the sorts of people who are victims but may not be recorded in official statistics drawn from crimes reported to the police.

In order to identify victims of crimes – which is the aim of this section – crime surveys, and not official police reports, provide the most accurate information.

Identifying the victims

Crime surveys show that not everyone is equally likely to be on the receiving end of a crime. In general, two contributory factors influence how likely people are to become victims:

Personal characteristics and vulnerabilities:

If you have a disorganised lifestyle, don’t look after your property or are less able to look after yourself, criminals may take advantage of that situation.