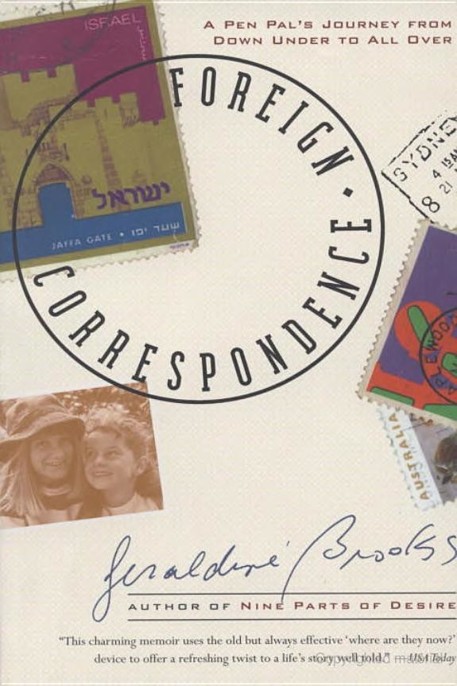

Foreign Correspondence

Read Foreign Correspondence Online

Authors: Geraldine Brooks

FIRST ANCHOR BOOKS TRADE PAPERBACK EDITION, JANUARY 1999

Copyright © 1998 by Geraldine Brooks

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Anchor Books in January 1998.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Anchor hardcover edition of this book as follows:

Brooks, Geraldine.

Foreign correspondence: a pen pal’s journey from Down Under to all over / by Geraldine Brooks. — 1st Anchor Books ed.

p. cm.

1. Brooks, Geraldine. 2. Foreign correspondents—Australia—Biography. I. Title.

PN5516.B76A3 1998

070.4′332′092—dc21

[B] 97-15413

eISBN: 978-0-307-77364-7

v3.1

To the memory of Lawrie, and to Gloria

… nothing is more sweet in the end than country and parents ever, even when far away one lives in a fertile place …

—The Odyssey

CONTENTS

12 Breakfast with the Queen of the Night

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Martha Levin and Elise O’Shaughnessy for convincing me to write this book; Darleen and Michael Bungey, Miki Bratt, Sarah and David Chalfant, Charlie Conrad, Elinor Horwitz, Brian Hall, Gail Morgan and Tina Pohlman for their comments on its early drafts; Joshua Horwitz, all-purpose sage; and Sara Mauck, without whose help it wouldn’t have been finished.

Above all, I would like to thank the two men in my life: Tony, who put the idea in my head and then helped to get it on the page, and Nathaniel, whose full-throated comments and occasional efforts at the keyboard made it easier to reenter the world of my own childhood.

1

Post Marked

Post Marked

It is a hot spring day and I am in the basement of my parents’ house in Sydney, sorting through tea chests. Pine floorboards creak above my head as my mother steps beside my father’s bed, checking his breathing mask. The old floor is thin and while I can’t make out her words I recognize the tone, its veneer of cheerfulness layered on anxiety.

From my father, propped up on pillows, I hear nothing. He barely speaks anymore. His voice—the beautiful voice that once made his living—is silenced by the simple effort of breathing. He is staring toward a picture window that frames a view of ocean through a fluttering fringe of gum leaves. But he can’t see it. His eyes, almost sightless now, are the whitened blue of faded cornflowers.

When my father moved to this beach house just after his retirement, he should have had the leisure to sort his old sheet music, to work on his half-composed tunes, read his cricket books, enjoy his correspondence. Instead, he became ill that year and never found the energy even to unpack. So I have come

down here to do it, because I don’t think I will have the heart to face these things once he is dead.

The dirt floor of the unfinished basement is cool against my bare legs, and I take my time. Twelve years of dust has filtered through the flimsy lids. Spiders scurry away, indignant, as I disturb them.

My father squirreled away everything. There are yellowed news clippings about his career as a big-band singer in Hollywood and Hawaii in the 1930s, before he came to Australia. There are dozens of dog-eared photographs of musicians with frangipani leis lying incongruously against their tuxedos; even more of Australian army mates in slouch hats at the Pyramids, in Jerusalem’s Old City, among the huge-leaved trees of New Guinea.

And there are letters, piles of them. Replies to every piece of correspondence my father ever wrote. He wrote, I realize as I unfold the brittle pages of fifty-year-old letters, to everyone. From 1931, there is a two-line note from Albert Einstein, in verse, responding to a request for permission to perform a ditty about him that my father had composed. Einstein writes: “Though somewhat silly, I don’t mind—there’s no objection I can find!” There is White House stationery—a 1969 reply from the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers thanking my father for his “good letter” on interest rates. There is a 1974 response from the office of Rupert Murdoch answering my father’s complaint about the creasing in his broadsheet newspapers. And a letter from an acoustical expert thanking my father for his suggestions about raising the height of a concert-hall floor to improve the way sound carries.

Each letter is a small piece of the mosaic of my father’s restless mind, its strange mingling of global interests and nitpicking obsessions. Some of the replies raise questions: Why did he write to the Israeli Minister of Defense in 1976? Where is the poem he wrote about Winston Churchill that the Australian

Prime Minister thanks him for in a 1958 letter? My father is beyond answering such questions now. I have left it too late to ask.

Near the bottom of a tea chest is a thick pile of airmail letters that raises an altogether different set of questions. Held by a withered rubber band, they are addressed, in various childish handwritings, to me. As I pull them out and blow the dust off, I recognize them as letters from my pen pals—from the Middle East, Europe, the United States.

I stare at them, puzzled. It was my mother who saved our school report cards, our drawings and poems, old toys and memorabilia. While I have never doubted that my father loved my sister and me, he rarely involved himself in the day-to-day business of our lives. Yet here, among his things, is more than a decade of my correspondence, from 1966, when I discovered pen pals, to 1979, when my parents moved to this house.

When I wrote to these pen pals, in the late 1960s and 1970s, my family inhabited a very small world. We had no car, had never set foot on an airplane and, despite my father’s American relatives, never thought of making an international telephone call.

In the evenings, families in our neighborhood would gather on the front verandas of their houses and wait for the “southerly buster”—the big thunderstorm that would break the heat, lay the dust and leave the air cool enough to allow sleep.

I was waiting, too. Waiting for something to happen, and wishing that I lived in a place where something did. Except for relentless coverage of the British royal family, Australian newspapers paid little attention to foreign places. The nightly TV news was more likely to lead with the coliform bacteria count at Bondi Beach than the body count in Vietnam. Yet, at school, our history books were filled with tales of elsewhere. The Great Men—and they were all men, in those days—were British,

American, German, French. I was aware from religion class that a few women had made it to greatness via sainthood, but they came from even more distant-sounding places—St. Theresa of Avila, Bernadette of Lourdes. A St. Margaret of Melbourne or a Diane of Dubbo was clearly out of the question.

My father’s escape was the yellow-painted metal mailbox on a post by the privet hedge. Almost every day it contained a letter for him from somewhere else—flimsy aerograms or heavy bond paper with official-looking seals. At the age of ten I learned that it was possible for me, too, to write to strangers and have them write back to me. Suddenly, I could see a way to widen my world by writing away to all the places where I imagined history happened and culture came from. When the letters came back from Vaucluse in France or Maplewood in New Jersey, I studied the foreign images on the stamps and dreamed myself into the lives of the writers.

And now I have their letters again in my hands. I sit in the basement, reading, as the light slowly fades and the surf thuds on the nearby beach. Oldest of all, nibbled around the edges by silverfish, are the letters from my very first pen pal, a twelve-year-old girl nicknamed Nell who lived just across town, and in a different world.