Forbidden Broadway: Behind the Mylar Curtain (4 page)

Read Forbidden Broadway: Behind the Mylar Curtain Online

Authors: Gerard Alessandrini,Michael Portantiere

At the time, I was trying to write real musicals; I was in Lehman Engel's BMI workshop. When I showed the Burton lyric to friends, they all thought it was hilarious, so

I was encouraged to write parodies of other shows and performers.

My takeoff on "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina" came about after I saw Patti LuPone

sing the song on the Grammys. She was literally weeping while she was singing; I was

watching with some friends, and I jokingly said, "She's not crying because she's into

the drama of the song, it's because Barbra Streisand bought the film rights for Evita."

Everybody laughed, and that spurred me on to write a parody lyric:

Then I wrote a Lauren Bacall/Woman of the Yearlyric, inspired by her performance

on the Tonys. Again, I was watching with friends. When Bacall sang, "I'm one of the

girls who's one of the boys," somebody-I think it was Peter Brash-said, "I think she's

one of the girls who's really a boy." That was all I needed to get me going.

While I was working at Lincoln Center as a maitre d', I had lots of time to jot down

lyrics. I would be at the host stand, and sometimes it would get very busy, but mostly

I'd stand there for hours with nothing to do. So I'd write parody lyrics on these big paper placemats. I wrote out the Burton,

Bacall, and Patti LuPone in Evita spoofs.

On my breaks, I would call friends and

sing the lyrics into their phone machines. (People had phone machines

in those days.)

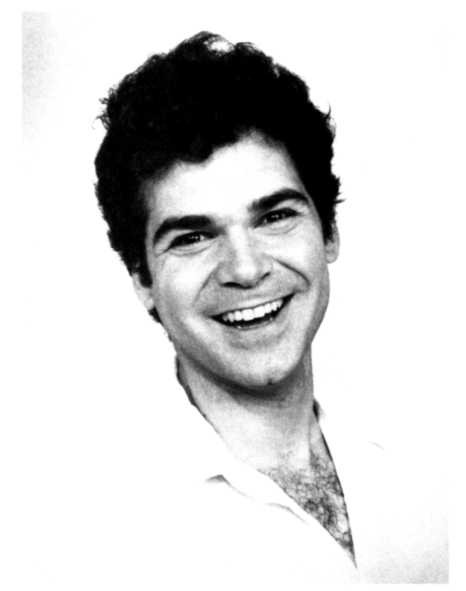

Gerard Alessandrini in the Reagan years.

During the summer, the host stand

was moved outside to the plaza, near

the fountain. One day, the wind blew

my whole set of lyrics off the stand, and

I thought they were gone forever. But

my manager, Bob Arnold, came up to

me the next day, grinning from ear to

ear. He was holding a bunch of crinkled

papers, and he said, "Somebody found

these floating in the fountain last night.

I read them and I thought they must be

yours." The papers had gotten wet, of

course, and the ink had run a bit, but you could still read the lyrics. Thank heaven Bob rescued them and had a good sense

of humor, or there might never have been a Forbidden Broadway.

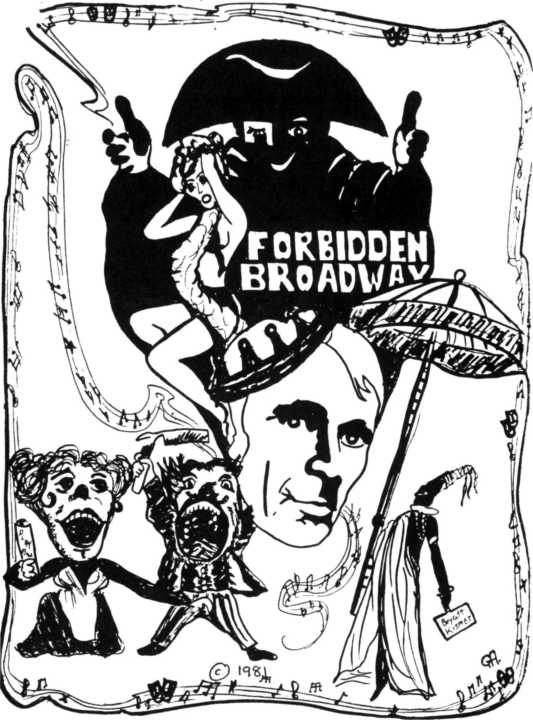

Gerard's cover art for his original Forbidden Broadway folder.

At the time, I was also studying musical theatre at The New School with Aaron

Frankel, who has been a great mentor and friend to me. All of us would bring in songs

from book musicals we were working on and present them to the class. There would

usually be some time left at the end of each session when we would entertain each

other, so I thought, "Let me see how they like these parody lyrics." Everybody loved

them, and Aaron said, "You should put those songs into an act and do it at a nightclub

somewhere."

I took his advice to heart, but I didn't want to perform the songs alone, since many

of them were about Broadway divas and I really wasn't into drag. So I enlisted the help

of a talented singer-actress-comic genius I knew. She was as unique as her name, Nora

Mae Lyng, and I had always wanted to write a show for her.

I had already come up with the Forbidden Broadway concept; I kept the lyrics in a

folder that had that title on the cover, along with my own cheesy, hand-drawn version

of what the logo art would look like. It featured a grinning and winking Amadeus hovering over a 42nd Street chorine, plus the face of Richard Burton, a Timbuktu chorus

boy, and Mrs. Lovett grabbing the crotch of Sweeny Todd. It was a mess, but the point

of view was all there. (To this day, whenever I do a new edition or show, I sketch out

the poster art first. That helps me set the tone.)

Another friend of mine who was also wonderfully supportive and encouraging at

the time was Pete Blue, whom I had met in Aaron's workshop. Pete and I tried writing

a few songs together, and we joined the BMI workshop as a team. During his off hours

from his job as conductor and pianist for the original Broadway production of The

Rest Little Whorehouse in Texas, Pete was generous enough to help me put together

Forbidden Broadway as a club act.

By the summer of 1981, Nora, Pete, and I were ready to go. The first presentation of

Forbidden Broadway was in June 1981, in Peter Brash's living room. Nora and I sang

about fifteen songs, with Pete at the piano. We used "costumes" from our closets,

evening wear and hats. The audience consisted of Peter; his partner, Jim Lynnes; my

friend Laura Henry; and Nora's husband, George Kmeck. They were rolling on the floor

with laughter, and I thought, "Maybe this really is a good idea for a show."

Someone at Peter's said, "You know, they have open mike at Palsson's tonight." So

we picked ourselves up, walked over to Palsson's in our evening wear, and asked if we

could do our material. One of the men in Aaron's New School workshop was there that

night, and he knew Sella Palsson, the owner, pretty well. He told her, "You should let

them get up and do these songs. They're very funny."

Nora, Pete, and I performed for about forty minutes, and it went so well that the

Palsson's people asked if we'd like to be booked there for a full evening or two that

summer. I thought it was a great idea, but I couldn't agree to do it when they wanted because I was set to do summer stock. So they

booked us for two nights in November, and I

went off to play Curly in Oklahoma! at Keene

Summer Theatre.

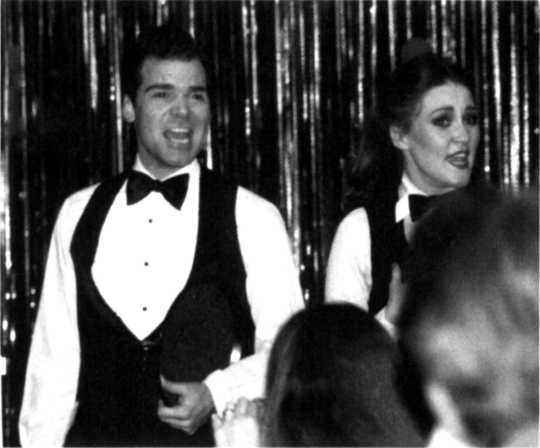

Gerard and Nora Mae Lyng, dressed as waiters, storm the

stage at Paisson's for the very first performance of Forbidden

Broadway.

Laura Linney played "fall-down girl" in that

production; I think she was about fourteen

and I was twenty-three. At the time, I was also

working furiously on a musical version of Scar-

arnouche, and I kept telling Laura about this

great new show I had. When we met again years

later, after she had become a film and theatre

star, she told me: "I remember how you said

you were writing a show that was going to be

a big hit when you got back to New York. The

next thing I knew, I was reading about Forbidden Broadway. That was so encouraging to me

as a young artist." And I said, "Well, great, but

that wasn't the show I meant."

In the fall, we got ready to do Forbidden Broadway at Palsson's. They had cabaret

shows in the upstairs room, performed on a tiny stage in front of a Mylar curtain that

seemed oddly appropriate for our "glamorous but trashy" take on contemporary

Broadway. I was still working as a waiter and host at the Avery Fisher Flail restaurant;

that's how I first met people like Leonard Bernstein, Comden and Green, and Beverly

Sills, but I wasn't talking to them about music, theatre, or the arts. My conversations

with these luminaries never went far beyond "Dear boy, could you get me a few more

of those delicious buffalo chicken wings?"

I was concerned that my singing and acting career was stuck in neutral. Perhaps I

was even angry. But nothing feeds comedy like a little anger, and I was ready to blow

off some steam. One day, I was bitching to Peter Brash, who had gotten a job as a gofer

for the soap opera The Doctors. (He's now an I:mmy Award-winning soap writer.) Peter

said, "Don't you have a show at Palsson's next week? Is anybody coming? I'd better

help you print up some flyers and programs." (Don't tell anyone at NBC, but we used

one of their copy machines to do just that.)

Then Pete Blue came to me and said, "I can't play the show at Palsson's because I

have to play Whorehouse." I naively thought, "Well, we'll just get another pianist." I

approached a friend of mine at BMI, but we didn't have any of the music written out,

and he couldn't handle it. I thought, "Oh, my God! I have a show in thirty-six hours

and no pianist. But I can't think about that now; I'll think about it tomorrow."

The next morning, I called Nora and asked her, "Do you know any pianists? At this

point, anyone will do." She said, "Yeah, I know a great one: Fred Barton." We brought the lyrics to Fred, with no music at all. He looked at the lyrics, and he knew the melodies and arrangements of the songs so well that he played everything perfectly from

memory. Instant chemistry!

So Nora and Fred and I did the show at Palsson's for two nights-and, to this day,

I have no idea where the audience came from. I had invited a few people, Nora's

husband was there, Fred had asked a few friends. As I said, we had printed up some

flyers, but I had forgotten to give most of them out. Still, the room was completely

packed for both performances. Even Hugh Fordin from DRG Records was there. Word

had somehow gotten out that the material was fun and Nora's performance was

something special.

For two nights only, we did the entire eighty-eight-minute show ourselves, with

no act break. In order to give Nora and myself a breather, I had handed Fred a parody

that bemoaned all the imitation Sondheim writers I was meeting in the workshops at

BMI and The New School. It was called "Too Many Sondheims."

I remember that the show was a little much for Nora and me to handle on our own.

By the time we had evisceratedAmadeus, Evita, My Fair Lady, Timbuktu(!), Merrily We

Roll Along, 42nd Street, The KingAnd I, and Woman of the Year, we were exhausted. We

started missing cues because we couldn't make the costume changes without help;

we dripped with sweat through the entire show, and we could hardly keep a straight

face. But the audience ate it up.

The success of these two performances was such that Palsson's offered to book us

for a run. Someone suggested we add two other performers and turn the show into a

full-fledged revue. I liked the idea, because I had written a number of other parodies

that required at least four actors. It would also take a lot of the performing pressure

off Nora and me. So it was on to Palsson's Cabaret Theatre. That's "Theatre" with a

capital T-and that stands for "Trouble!"