Following the Water (2 page)

Read Following the Water Online

Authors: David M. Carroll

Streamside thickets and occasional taller trees along the stream write their signatures on the water, an undulating script on an ever-moving page. Even these shadows have their identities: the whiplike lines of silky dogwood, broader trailings of alder stems, bolder strokes of red maple trunks, and sweeps of white pine crowns. Are these shadows or transparent reflections? They cut narrow slits and wider openings in the clear water, which the light of day would mask. I shift my head, looking in from as many different angles as possible, trying to catch sight of a wood turtle, tucked in or perhaps even shifting about, as sometimes happens as the long overwintering approaches its conclusion, even when the brook is only four degrees above freezing. But it is enough to see the streambed again, its sand, cobble, and stones, sunken branches and drifts of leaves.

I raise my head and look upstream. Can I be looking at a wood turtle? The shape is far enough ahead that I cannot be certain, and my disbelief that a turtle would be so exposed, up on an open, muddy mound of stream bank surrounded by snow and ice, prevents definite recognition. But as I advance I begin to read it as a turtle, and the reading

is disturbing. The angle, something in the way that so-familiar sculpted shape is settled, is sharply out of keeping with any search-image I have. Wood turtles always place themselves in harmony with their surroundings, with the configurations of the earth or stream bottom on which they have settled or over which they move. This gestalt has struck me as unfailing. Except when they are compelled to cross a road or open lawn, wood turtles are never out of place.

Even from some distance, as I wade, looking into the turtle's face, I know that something is terribly wrong. Where is that light in the eyes, the light of life and reflected day that shows before the gold-ringed eyes themselves can be clearly seen? What are those shadows, dark pockets on either side of the jet black head? Where are the legs, black-scaled, with vivid flashes of red-orange skin color that should be part of the pattern? Riveted by this troubling vision, I never look away as my feet find their way over the streambed and I wade to the turtle. A profound confusion comes over me, the elation of seeing that first turtle up out of the water at the end of hibernation mingling with a reality I do not want to see. The turtle's eyes are closed, her legs are gone.

I pick her up. Her shell is so familiar, that shadowy umber brown carapace with yellow-gold striations, like faint flecks of sunlight. Tiny notches I have made along her marginal scutes identify her. An adult female, she is one of the first wood turtles I documented along this brook, where I have

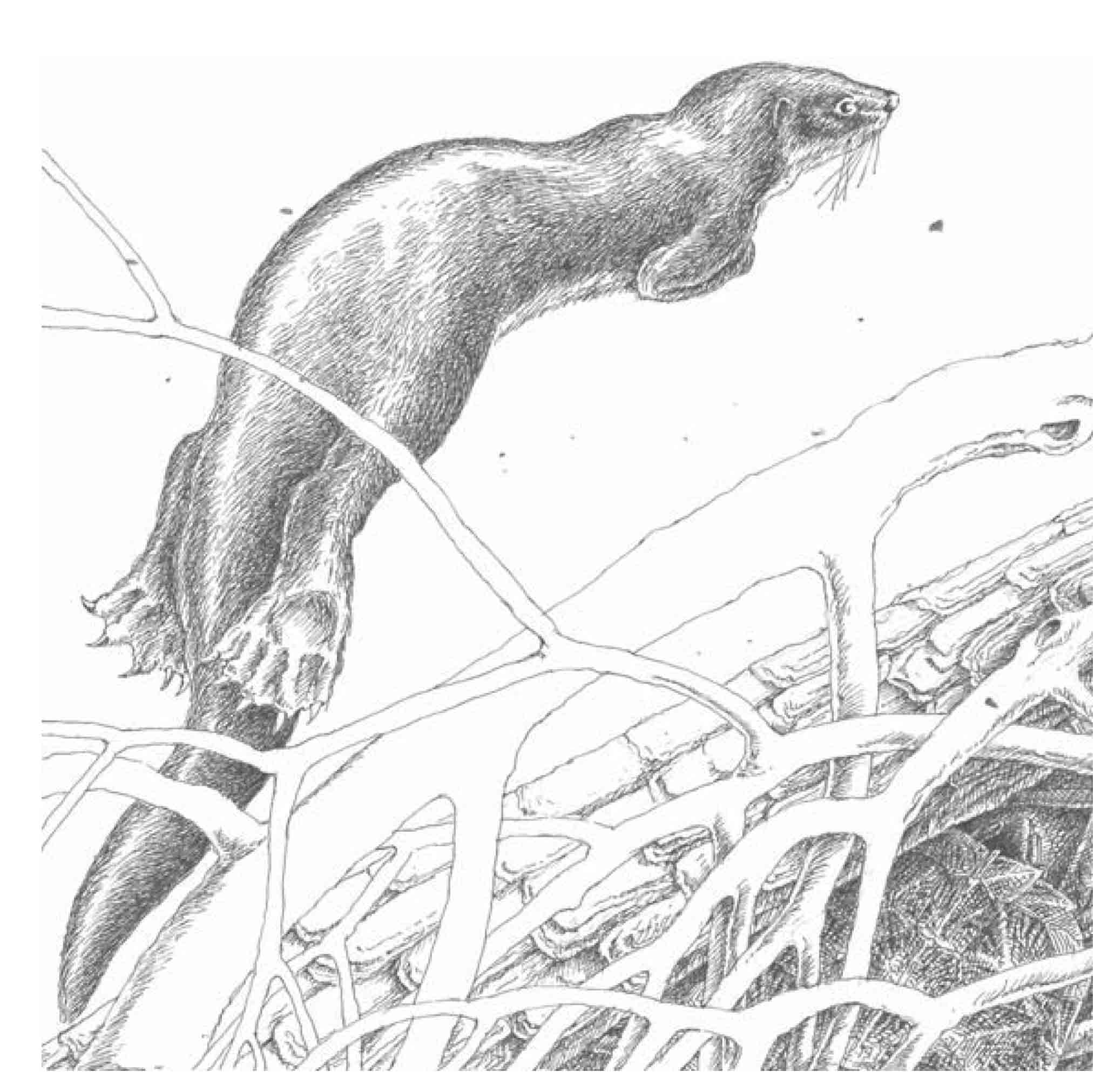

been recording them in notebooks over the past twenty years. Her head does not move, there is no sign of life in her tail as I move it from side to side. A few tiny bubbles appear at her nostrils, perhaps a last flicker of life. All of her right front leg is missing and the lower half of her left front. Her right hind leg has been eaten away from the knee joint down, and her left hind leg is only a shaft of bone to where the knee joint was. How did she get up here? My crowded thoughts and questions settle out, and I realize that of course she could not have climbed up onto this mound but was left here by the otter who discovered her in her winter hold in the stream and wrestled her onto land to work at her, force out at least a foot to eat from the fortress of her shell. There is not one tooth mark on her carapace or plastron; predators know there is no biting through the shell of a wood turtle this size.

A sense of foreboding comes over me, as it did five years ago when, at this same seasonal moment, I discovered an adult male who had lost both front legs and then a six-year-old who had been bitten through and killed. I am familiar with reports by others who study turtles of heavy losses on colonies of painted and snapping turtles by otters preying upon them during their hibernation. I found no further evidence of such predation that year, but I wonder what I will find when the wood turtles here begin their first streamside basking of this new season.

Otter and hidden wood turtle.

I set the turtle back down. The temperature will drop well below freezing tonight. If the least flicker of life does remain within her, it will be extinguished. A life of decades, likely more than half a century, has come to an end. Borrowed stardust is at length returned, and the flame that burned within passed on. In silence, the water flows on by.

Alder shadows creep across the snow. This is an aspect of what takes place in the stream, along its banks and beyond. My human-turtle connection does not allow me complete objectivity. But my deepest griefs are human-driven, not by the death of any individual living thing within the ecology, but that of the ecology itself.

1

APRIL.

The crowns of the royal fern mounds have melted free, but they are islands of pale ocher and sienna (warm in color and in what they collect from the sun), outposts of thaw in the encircling acres of ice and mounds of snow that still prevail throughout the great alder carr.

Winds, strong and chill, stir that familiar, near-at-hand rustling in the dry sedges, as though something with more substance than wind were moving through them. Distant low roar in the upland pines beyond the swamp. Not long ago I heard a few red-winged blackbird calls, distant and windblown, coming from the border of the brook.

***

Woodcocks know the snow's first melting away from the bases of alder mounds, the slightest openings achieved by upwelling groundwater and seeps in the alder carr and aspen thickets; all of life is intimately attuned to the narrowest of margins.

Deer tracks are set in the footprints I left in the lingering snowpack at the edge of the swamp yesterday. I so often take to deer trails; here one has taken to mine, step for step.

Wading among the sallows, a broad swath of just-overhead-high willow shoots at the outer edge of the deeply flooded alder swamp, I see a pair of black ducks leave silver streaks on the dark water as they stealthily, silently glide out of sight. Secure in the same screening blur of emergent shrubs, the ducks, of a species that is ever alert and seems to be always on edge, do not burst into the air in wild-winged flight, their almost invariable reaction upon catching sight of me. Losing myself among the countless fine branches, I enter one of those watery thickets in which everything but the present moment and place is brushed away from me. I can feel myself disappearing. My awareness shifts to the pliant stems immediately surrounding me.

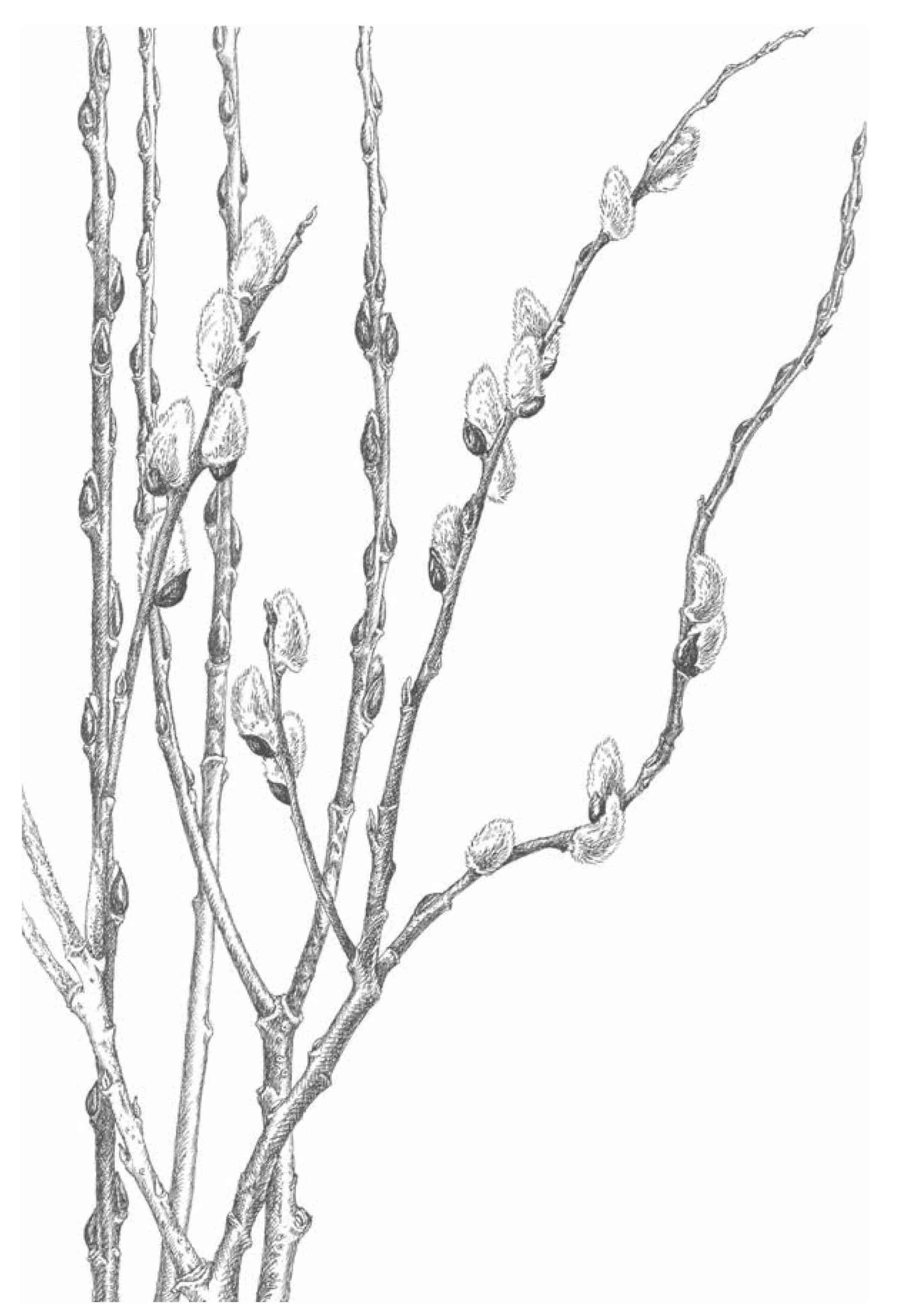

As my focus turns to the just-emerging catkins, their bud scales and leaf buds still pressed tight against lustrous stems, I become seeing eyes and touching hands only. A

Sallows.

song sparrow sings and I become listening ears as well. In the maze of wandlike branches above the floodwater, runoff, and melted snow that have escaped the banks of the brook to inundate this hollow, I read the supple growth of the willows, stem by stem. As they assume the colors of quickening life, they vary within their own species and among the three or so species that grow here. Some stems are green-gold, streaked with a sheen of sunlight. Others are gray-green, a rich umbered purple, or dull ocher-green mottled with a smoky charcoal gray. The tiny leaf scales range from greens to carmine.

The scales of the flower buds respond to the season. Some have almost imperceptibly separated from their branches to show tips of fine white silk. Others have opened almost fully to unveil soft catkinsâpewter gray, silver, ivory white. The scales that have sheltered these flower buds through the winter fall away as I brush among their stems. Willow catkinsâfirst flowers of thaw in the shrub swamps and along the borders of brooks, belonging to the wind and water of winter's fitful transition to spring, nascent in a newborn season, open to wild pollinators.

I begin to wade out of the alder carr. My left foot has gone numb. The wind has abated, and red-winged blackbirds have advanced into the alder thickets. Their evensongs ring clearly in my ears. A mourning dove's plaintive calls descend from

a high pine on the upland ridge. I hear Canada geese trumpeting but cannot make them out against the low sunlit sky to the west. As I scan for them, I hear that familiar rain of twittering, then see a flock of tree swallows wheeling directly overhead. A great blue heron departed from the marsh beyond the alder lowlands as I entered them, and on my way here I heard a phoebe and a robin. In leaving the shrub carr I cut a wand of beaked hazelnut on which the tassels have lengthened in the time since I walked in. The threadlike, bright magenta tips of the female flowers are showing, familiar signs that the season has come back in a day.

It will be a while before I see the next spotted turtle or the first vernal-pool amphibians. Cold, blustery winds and a dusting of snow in the night. North by northwest winds are blowing a smoke of snow from the high white pines. A cardinal sings, but it is cold, a winter's-edge day in early April sun, the sky a hard, cold blue.

Water-murmur and the distant evening song of a robin. The high crowns of the pussy willow thicket have come into full bloom. The sun has slipped behind the western hills as unrelenting winds bring a snow squall down from the mountain. The snow melts upon touching the stream bank, dissolves as it swirls into the brook.

***

The run of chill, wind-blasted days and nights of hard frost continues. There is no sun. Sharp-toothed winds whistle along the little silver-running brook that divides the gray-trunked, low, level expanse of the red maple swamp, gray trunks accentuated by the muted yet radiant gray-green glowing of lichens in a time of cool, abundant moisture. The maples rock and clatter together on high, where a few first flowers open. Several trees reach up from each stump left after the last cutting in the swamp. Ancient roots, perennial enough to seem eternal, could send up new sprouts following cuttings by man or beaver every year for decades until, left alone for a time, they become trees again and re-claim their forest.

As I approach the grassy vernal pool in the late afternoon, I hear a deafening chorus of wood frogs and peep frogs ringing out. Within this ear-impacting din I can make out the rollicking splash of the wood frogs. The power of the midday sun working on water in mid-April: when I passed by here just four and a half hours ago I heard only a few tentative calls. Now those isolated eruptions that seemed to be questions have been answered. I wade among the wood frogs as they leap and roll through the deeper trench just out from the emergent winterberry thicket, their traditional site for depositing two enormous communal egg masses each spring. The frogs do not perform their customary multitude-in-unison disappearing act; they have become too aroused by their own inner fireâperhaps a strange concept, since they are deemed in human terms "cold-blooded"âand by the heat of the season to pay any heed to my approach or my stationary looming over them. But they do take immediate notice as a bittern wings low over their orgy. This consummate frog predator, who can rise up out of nowhere even when there appears to be no standing cover, puts them down in an instant, abruptly silencing their tumult. The peep frogs shrill on. I imagine the bittern has been feeding well on the incautious male wood frogs. They will soon get their wits about them and resume their silent and secretive ways. For now they are the image and sound of wild abandon at the "at-last" breaking of spring.

Late in the day a robin sings incessantly, and a mourning dove calls repeatedly from the dense pine stand above the alder carr. Only the faintest sunlight shows in the alders, as the sun is about to disappear in the hazy sky, dropping beneath the pines of the low western horizon. It is breathless here, but as so often happens, I hear the wind in the high white pines to the east. Now robins call from roundabout, their distant, lilting song to the sun's setting and rising. Piercing even from across this great alder swamp, the calls of the red-winged blackbirds mingle with those of the robins. Sapling red maples here and there among the alders

spike the maroon-gray thickets with sharp red, the color of April's coming to life. This, the time of the red maple flowering, is the best time here and throughout the swamps and river floodplains, along the brooks and streams, wherever water stands or flows. After all these years I try to fill up on this signal moment, but there is no keeping it. It always comes to this: I can only return, again and again, and be here in this too-brief time. The temperature drops quickly, sharply, with the setting of the sun.