Flyaway (6 page)

Authors: Suzie Gilbert

BACKING TOWARD THE CLIFF

From what I could see, our grackles were having a fine time in their flight cage. The younger one was somewhat tentative, the older already swaggering. Gender was anyone's guess, so I declared the younger one female and the older, male. Both had a repertoire of chirps, clicks, and that endearing grackle sound of heavy metal being dragged across concrete. Although they were still young, you could already catch glimpses of the fearless, aggressive personality of the adult grackle. We christened themâin order of ascending ageâNull and Void.

During their first two weeks I visited them twice a day, keeping our in

teractions to a minimum, hoping they would come to view me as a relatively boring food source rather than a parental figure or a fun pal. I combed through my ever-expanding bookshelves for specific information on readying captive-raised grackles for release, surfed the Net, and peppered my wildlife rehab electronic mailing list with questions.

According to the veterans who had released captive-raised songbirds, the two most important release criteria were the bird's ability to relate to its own species and its ability to forage for its natural food. Slowly but surely the grackles were beginning to interact more with each other, although Void occasionally acted irritated with Null, like a cool kid with a bothersome younger sister. The “natural food” part took a bit more doing. I looked up “Grackle, Common” in Marcy Rule's

Songbird Diet Index

, one of the songbird rehabilitator's bibles, which contains both the natural and captive diets of well over 100 species of songbirds. Armed with clippers and gloves I scoured the countryside for various berries, weeds, and grasses gone to seed; brought them home; and arranged them artfully around the flight to encourage the grackles to forage. Meanwhile, the kids and their friends took to the fields with buckets and bug boxes and returned with beetles, grubs, caterpillars, crickets, and centipedes. The first time they dumped a bucket of bugs onto the flight floor the grackles danced backward, their yellow eyes bright with alarm, as they were used to their relatively slow-moving mealworms and not things that hopped and raced across the ground. Soon, however, they were outmaneuvering the crickets and expertly turning over leaves and wood chips to find the centipedes hidden underneath.

The wound under the house finch's eye had healed and he was back in the second flight cage, keeping company with a song sparrow recovering from a broken wing. The robin who had lost the bird fight was still healing, his prodigious appetite no doubt fueled by dreams of revenge. My plan to give the blue jays to Joanne was loudly vetoed by the kids, who had decided that raising baby birds was a grand and worthwhile project, and seconded by Joanne, who was swamped with a dozen or so nestlings of her own.

The five remaining nestlings had rallied and were eating like champs, although Norbert, the second smallest, developed foot problems and needed snowshoes. A “snowshoe”âused to straighten out a bird's foot when it is curled and clenchedâis made by affixing a piece of lightweight padded plastic, made to order for each bird, onto the bird's open foot using special tape. Three days was sufficient to straighten out Norbert's toes, but meanwhile one of the others had developed bloody diarrhea. A fecal test revealed protozoa, so the whole crew had to be wormed.

And then Jill called.

Jill Doornick is the founder of both Animal Nation, an animal rights and rescue operation, and Westchester's Wildlife Line (WWL), a group of rehabbers based in the county south of me. When people call the WWL, they choose from a menu of wildlife forms (“For small mammals, press 1. For reptiles and amphibians, press 2⦔). They then hear a recorded message telling them what to do and whom to call.

“There are no secrets around here,” said Jill. “I've heard all about you and I know you have two beautiful flight cages. What I'm hoping is that you'll let me list you on the hotline. We don't have enough bird rehabbers and everyone is always swamped, and it would be such an incredible help to all of us.”

“I'm sorry,” I said. “I have the two flight cages, and I'm happy to take any birds who need them. But I can't take injured birds. I don't have the space and I have two kids in elementary school.”

“That's okay!” said Jill enthusiastically. “My kids used to help me rehab! Can you do babies? They don't take up much space. A lot of rehabbers work during the day and can't take nestlings to work. Are you home during the day?”

“Yes,” I said, “but the kids get home at three.”

“Do they like birds? Can they help you feed babies?”

“Well, as a matter of fact we have five blue jays, but that was just an accident and there's no way⦔

“There! See? You can't imagine what having you on board would do. We get so many calls for these poor birds, and we just don't have enough people to take them, especially in your area. It's awful.”

“I understand that,” I said. “But⦔

“I'll tell you what,” she said. “Could you just provide information? Tell people if they've found a baby bird to put it back in the nest, tell them to leave the fledglings aloneâyou know, that kind of thing. That way the other rehabbers won't have so many messages backed up. And if it's really a rescue situation and you can't do it, you just tell them to call someone else.”

I considered it. How could I say no to just giving out information?

“Please help us,” she said. “We really, really need help.”

“All right,” I said.

I hung up the phone, wondering what sort of pact with the devil I had just made. I needed to take a run and think things through. I glanced down at my weekly calendar and saw, to my delight, the word

goshawks

scribbled in purple magic marker.

By now the goshawks' eggs would have hatched and the nest would be filled

with nestlings. Since our audio encounter her voice had haunted me, echoing through my dreams, winding through my head like an old song I couldn't dislodge. I fed the blue jays, then donned my running clothesâshorts and an old tee-shirt riddled with parrot beak holesâand added a pair of ski goggles, just in case I met up with one of the parents and they were not happy to see me. I pulled the goggles over my head and around my neck, grabbed a small pair of binoculars, and took off into the woods.

The June woods were welcoming, filled with dappled sunlight and the sounds of summer, and the farther I ran the better I felt about agreeing to list my number on Jill's phone bank. I still had control over the situation; I could provide information to the public, which I was more than willing to do, and say no to anything that would upset the household equilibrium. Feeling confident and decisive, I slowed down as I neared the nest area.

Slightly smaller than the more familiar red-tailed hawk, the adult northern goshawk has a slate gray back and wings, a pale gray chest, and a dark band of war paint across its eyes. Like many other raptors, the female is noticeably larger and heavier than her more agile mate, which allows them to hunt prey of different sizesâan advantage when there are hungry nestlings to feed. The female is also louder and, around her nest, more aggressive.

I dropped down to a walk, squinting through the slight camouflage provided by hemlocks almost stripped of their greenery, and found the nest filled with whipped cream. At least that's what it looked like at first: a soft white froth atop a shadowy structure, lightly trembling and shifting until it suddenly revealed the dark eyes of a nestling goshawk. There was another beside the first, maybe even two, but I was too far away to see them clearly. I was so trans-fixed that several seconds must have passed before I realized that the male goshawk was standing on the edge of the nest, staring at me intently. I backed away slowly, hoping if I put some distance between us I could watch them for a minute or two, then leave them all in peace. I continued until I came to a fallen tree, then quietly sat down and raised my binoculars.

As soon as I started to focus on the nest I felt a strange sensation. It was a

slight discomfort, a shiver, a feeling that made me think, “Uh-oh,” although at that moment I was too slow-witted to figure out why. I lowered my binoculars and there, at eye-level and not ten feet away, was the female goshawk.

When predators come for you, you know it. And they know you know it.

Like a snake before a snake charmer I sat dazzled, held captive by her unwavering red eyes. I have no idea how long we stared at each other. Finally I did something that was logical for a birder, but wildly illogical for a birder sitting a few feet away from a hormonal raptor: I raised my binoculars.

I suspect that from the goshawk's point of view, raising the glasses to my eyes not only made me even uglier and more misshapen than I was before, but raised my threat status from code orange to code red. In any case, she launched herself forward off her branch just as I launched myself backward off my log.

She flew over my head and landed screaming on a high branch, her voice ringing through the woods:

kek-kek-kek-kek-kek-kek-kek!

I backed away, keeping in mind that while a great horned owl might be

capable

of doing more damage to its chosen target, a northern goshawk is

willing

to do more. Once again, she hurled herself straight for my head. When she was several feet away I dropped to the ground, and she banked, headed up, and landed on a tree limb. I had dodged her first bullets not because of any vast raptor experience but because of my hardwired instinct for self-preservation; had I any control over my actions I would probably have simply stood there gaping, then shouted, “Oh, wow! Do you have any idea how cool you are?”

I continued to back away, hoping against hope that her mate wouldn't decide to join the assault, and I put a large, leafy maple between us. In response she leaped into the air, pumped her wings once, turned sideways, flattened her body, snaked around the tree trunk, and came sailing through the leaves at my face, knifing through the air like a shark through water, a sleek and vengeful Fury with a single goal. I ducked, she banked. We performed our duet twice more as I continued to retreat and she to chant her outrage, until she had driven me from her territory and banished me from her sight.

Safely out of range I did a victory dance of sheer exhilaration, suddenly un

derstanding the psyche of the disciple who waits for hours in the rain for a quick glimpse of the spiritual master. Far from the world that humans have reduced to tree stumps and pavement, the goshawk showed me a kingdom where my species gave me no unfair advantage, where I could see a fearless wild creature in all its glory, where I could participate in an ancient ritual that ended in a fair and just way. I turned in a slow circle and saw a nuthatch work its way up an old oak tree, two titmice peer at me from a striped maple, and a thrush sail by and disappear into the deeper woods. From the distance came the ascending echo of a pileated woodpecker. Theirs was the world in which I longed to play a part, in which I could witness the transcendent and perhaps even begin to atone for the sins of my own kind.

I raced back home, the forgotten goggles clutched in my hand.

DAYCARE

“Rrrrrrrrrrrrr,” growled Skye softly.

Holding the bug-filled tweezers above her head, she slowly serpentined them down to a tiny eastern towhee, a new arrival who had steadfastly refused to eat. “Rrrrrrrrrrrrrr,” she repeated, and to my amazement, the nestling promptly opened its beak.

“Airplane,” she explained. “Remember, you used to get me to eat by pretending the food was an airplane.”

The kids were out of school and day camp had yet to start, but those carefree summer days were now chopped into twenty-to thirty-minute segments. People would call to say they had found a nestling bird on the ground, and every once in a while I would succeed in getting them to climb into a tree or up the side of their house and put it back in its nest. More often than not there were complications: the nestling had an obvious fracture, the nest was forty feet up, or the bird had appeared out of thin air and there was no nest in the vicinity. If it was a weekend, I could occasionally get the finder to call Maggie or Joanne; more often than not, I would simply take it myself. The nestling would arrive, receive the standard-issue box and towel nest, and somehow join the schedule. I pressed the kids into service, and Skye became a master at getting reluctant babies to eat.

Nagged by guilt that I was neglecting my own children, I'd pack the nest

lings into a big wicker picnic basket with a hinged (thus closeable) top, place their food and supplies into a carryall, put the kids' stuff into a giant canvas bag, then drive to the pool or the lacrosse game. Mac and Skye would race ahead and I'd stagger after them, laden like a pack mule and muttering under my breath, then I'd set up shop under a tree while they expertly fielded questions from the circle of kids who would inevitably gather around us.

“They're blue jays. Those are finches, and that one's a cardinal. They eat bugs and dip. They eat all the time. No, you can't raise one by yourself; you have to have a special license to raise a wild bird. You once gave a baby bird bread and milk? Birds aren't mammals; they don't drink milk! No, don't

ever

give them water; if a baby bird opens his mouth and you squirt water in, you'll drown him. If you find a baby bird who fell out of his nest, just put him back; the mother bird won't care if you've touched him, she just wants her baby back.”

Fledglings were a different story. Fledglings are fully feathered and ready to leave the nest, but they haven't gotten the hang of flying and usually are still being fed by their parents. Often called “branchers,” they hop from branch to branch, occasionally missing their target and falling to the ground. In a perfect world this would not be a problem; they would simply hop around until they found a bush or limb to scramble up, and life would continue. However, thanks to the world of humans, when the fledgling falls to the ground it often encounters a cat, a dog, or a child.

Some of the people who found me through the wildlife hotline couldn't have been more helpful and concerned. “I can see the parents flying around,” they would say. “I've put my dog inside, and I've told the kids not to go near that area. What else can I do?”

“You did everything right,” I'd say. “Wait for an hour and check on him. If he isn't gone, then pick him up and put him on the highest branch you can reach. Then just leave him alone and let the parents take care of him.”

Others made me want to reach through the phone and grab them by the throat. “Oh, I couldn't possibly bring Mr. Whiskers inside,” they'd say. “He'd

be mad at me. Besides, everyone in the neighborhood has cats so if Mr. Whiskers doesn't get him, somebody else will.”

I tried mightily to find other rehabbers to pawn the fledglings off on, but there simply weren't enough of us. That first summer I ended up with a collection of fledgling robins, which meant that each morning I could be found bent double, bucket in hand, combing through dead leaves for earthworms.

“I'll pay you,” I finally said to the kids. “Fill up these containers and I'll give you each a whole dollar.”

“A dollar!” they said scornfully. “Is that all?” Disappearing into the woods, they quickly reappeared and handed me back the containers. I removed one of the lids, revealing a half a dozen of the biggest earthworms I'd ever seen.

“Jeez Louise!” I exclaimed. “Those are pythons! I want the robins to eat the worms, not vice versa.”

“Up to you,” said Mac, shrugging. “We can get smaller worms, but it's gonna cost you.”

Wild birds can't be kept in regular birdcages, as they will damage their feathers by brushing them against the metal bars. To supplement my collection of heavy plastic pet carriers I bought two reptariumsâroomy reptile enclosures made of light plastic frames surrounded by soft mesh. Filled with leaves and branches, they provided a safe and recognizable habitat for fledglings who had suddenly been taken from their own environment.

Young birds grow with astonishing speed, and there were mornings when I would peer into a nestful, marvel at their change from the previous evening, and feel lucky and privileged. The kids took their assistant duties seriously and were thrilled with their newly earned right to feed the birds without supervision. Occasionally, however, our inability to locate our dog-eared copy of the nestling identification book caused our conversations to spiral into absurd proportions.

ME:

Yup, it's cute all right, but I have no idea what it is.

MAC:

Maybe it's some kind of warbler.

SKYE:

Maybe it's a woodpecker.

ME:

Maybe it's an elegant trogon.

MAC:

I think it's a blue-footed booby.

SKYE:

Nahâ¦it's a dodo.

ME:

It must be some kind of strange dwarf condor!

MAC:

It's a miniature featherless moa!

SKYE:

It's half stork, half beaver!

ME:

Let's try feeding it an enchilada suiza!

MAC:

And some Cheez Doodles!

SKYE:

I think it wants a chocolate sundae with lots of sprinkles!

How many kids even know what a moa is? I thought triumphantly, somehow convincing myself that my children's ability to identify an extinct New Zealand ratite was far more important to them than having a mother with a decent amount of free time. The days were hectic but sometimes went fairly smoothly, leaving me with outsized feelings of capability.

Other days did not go as smoothly, leaving me with outsized feelings of inadequacy. As any rehabber will attest, problems tend to come in clusters. One bird will suddenly stop eating, another will develop a mysterious limp, a third will look a little “funny,” and then the telephone will start ringing.

“Can you take a single baby mallard?” asked the voice on the phone.

This was one of the days that were not going smoothly, and I was feeling rather peevish. “A duck!” I burst out. “You must be kidding me! I'm up to my eyeballs in blue jays and robins, and God knows what else, and I'm not even supposed to be doing babies! Out of all the birds I don't do, the ones I don't do the most are ducks!”

“Listen,” said the voice. “I must have called every rehabilawhateveritis in the state, and either they tell me they're full or they don't answer their phone. We're leaving for the airport in two hours and if I don't find somebody to take this duck we're going to have to just dump him back off where we found him.”

“Take him back to his parents!” I said.

“We couldn't find them. He was running around by himself. We looked all over for the parentsâbelieve me, we looked

everywhere

.”

“I don't have any duck food!”

“There is a feed store two miles from here. I will go in and buy the biggest bag of baby duck food they have. I can deliver the duck and the food right to your door; all you have to do is tell me where you live.”

“No way!”

“Please!”

“No!”

“Please!

If you don't take him he's going to die!

Please! You can't let him die!”

Eventually I hung up the phone. “âI don't do ducks! I don't have any duck food!'” I chanted nasally, mimicking my pathetic self as I trudged off to my purple three-ring binder to look up “Orphaned Mallards.”

The beauty of baby ducks is that they feed themselves. Unlike altricial songbirds and raptors, whose babies are born blind and nestbound, ducks are precocial; that is, 24 to 48 hours after their birth they're wide-eyed and racing around after their mothers. This made me feel better, as did the fact that the incoming duckling wasn't a wood duck. I had learned through the grapevine that most rehabbers live in fear of getting wood ducks, who are so shy and reclusive that they drop dead from sheer terror if you so much as glance in their general direction.

I went off to prepare a duck box, suddenly filled with gratitude toward the rehabber friend who had insisted on giving me a feather duster “just in case,” even though at the time I had insisted that there was no way I would ever need one. A duck box is a large shoebox with the lid attached on one side, allowing it to be easily opened and closed. An entrance hole is cut into the front. Another hole is cut in the top (the ceiling), into which is stuck an old-fashioned feather duster, so the feathers are in the box and the handle sticks out of the ceiling. A heating pad covered with a terry cloth towel is placed on the bottom, then the whole contraption is placed into a large topless cardboard box. The end result is a nice roomy enclosure, complete with a little house the duckling can run into

if it's cold or scared. The heating pad provides warmth, the feathers are an approximation of a mother duck. I put the whole thing on the washing machine, closing the folding doors just as the front doorbell rang.

A young couple stood outside the door, both wearing apologetic but determined expressions. The woman held a small canvas carryall, the man a very large bag of Unmedicated Game Bird Starter. Wordlessly, the woman opened the carryall.

I looked in. Staring back at me with an apprehensive expression was the tiniest duck I'd ever seen.

“Oh God,” I croaked. “Are you sure you looked everywhere for the parents?

Everywhere?

”

“I swear to you,” said the man, solemnly raising his right hand. “We looked

everywhere

.”

I carried the duckling into the kitchen, where John and the kids had materialized. The tiny duckling's appearance caused a waterfall of elongated vowel sounds, with only one family member withholding approval.

“Aaaaaaaaaah!” breathed Skye.

“Oooooooohh!” sighed Mac.

“Awwww!” crooned John.

“War!” shouted Mario.

We all looked at each other.

“I've never heard him say that before,” said Mac.

“Maybe African greys don't like ducks,” said Skye.

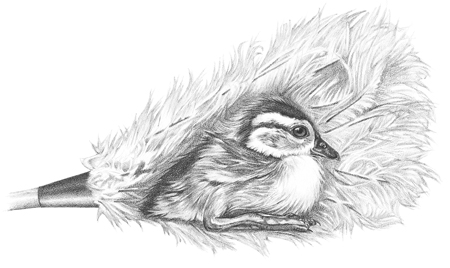

I put the duckling in the box and gave it a small tray of soaked food, which, after some encouragement, it ate eagerly. Afterward I opened the lid of the house, placed the duckling on the nice warm towel, and fluffed the feather duster around it, then closed the lid. There was a moment of silence, then a soft peeping.

“I'm going to name her Daisy,” said Skye.

“Daisy!” snorted Mac. “No way.”

“What would you call her?” Skye demanded. “Brutus,” she intoned deeply. “Lothar.”

“You know something?” I asked. “I'm not sure that's a mallard. I think it looks kinda funny.”

“What do you mean, âkinda funny'?” asked John.

“It's a scientific term,” said Mac. “I'll explain it to you when you're older.”

The peeping grew in volume and intensity. Soon the peeps were accompanied by soft thuds as the newly christened Daisy began attempting to hurl herself out of the box. From our various positions we could see the top of her head appear, then disappear, then appear again. Finally she levitated straight up and somehow landed on the rim of the box, where she teetered wildly before pitching off toward the bare floor five feet below. Before I knew what I was doing I'd thrown myself across the room like a star football receiver, landing flat on the floor and catching the duckling just before she hit the ground. I lay there silently, wondering if I'd broken any bones.

“Nice one, Mom!” came the appreciative chorus. “Do it again!”

Soon the duckling was back in the box. The box now sported a top made

of metal hardware cloth, the same material that encased the flight cage. As I listened from the living room I could hear Daisy's levitation efforts being thwarted by the wire top. Bonk! Peep, peep, peep. Bonk! Bonk!

“Awwwwww, she's lonely!” called Skye, picking up the ringing telephone and disappearing into her room.

She was lonely, all right, but it was seven at night and I didn't have any other ducks to keep her company. I covered the box with a towel, thinking the darkness might calm her down and make her sleepy. No dice. I continued to listen to the steady drumbeat of Daisy's head against the top of the box, desperately hoping she'd settle down before she gave herself a concussion or died of stress. Bonk!