Flood Friday (9 page)

Authors: Lois Lenski

When Mrs. Boyd came home one day with a kerosene lamp, the children were more excited than ever.

“To think these poor children are so ignorant, they’ve never seen an oil lamp before!” cried Mrs. Boyd.

“We learned about them in school when we were studying the olden days,” said Sally.

“We’ve

seen

them in antique shops,” said Barbara, “but we never knew how they worked.”

Mrs. Boyd showed them how to raise and lower the wick. They took turns lighting the lamp, putting on the chimney, blowing out the flame, and lighting it again.

“When I was a girl,” said Mrs. Nelson, “we lived in the country and it was my job to fill the lamps and keep the chimneys clean. I didn’t enjoy it much.”

“These girls are lucky!” The women laughed.

“Just press a button, that’s all,” said Sally.

In spite of the comforts at the Boyd house and their continued kindness, Sally could see that her mother was getting restless. She herself was becoming more homesick every day.

“Oh Mother, can’t we ever go home again?” she asked.

“Yes, dear,” said Mrs. Graham, “but not till the house has been cleaned up, disinfected and inspected. It’s knee-deep in mud now.”

“Knee-deep?” cried Sally.

“Yes, I mean it,” said Mrs. Graham.

Barbara was listening. “And here I complained because people were tracking in mud on our carpet.”

Each day, Mrs. Graham went away with Mrs. Boyd in her car. Mrs. Nelson stayed at the house in charge of the children.

“Everybody’s getting sick in town now,” Mrs. Boyd reported at the end of the week. “The typhoid shots are having their effect. Then, too, it’s the cold food and funny water. People can’t scrub—there’s no water to scrub with. The smell down town is horrible. I had to hold my hand over my nose—sewer gas, decayed matter, disinfectants and I don’t know what.”

“I spent the whole morning standing in line trying to get a pass to go to

my own home

,” said Mrs. Graham, discouraged. “We all need a change of clothes, since there’s no water to wash anything. I haven’t a cent of money and the banks are closed. I can’t buy anything—the stores are closed. A person can’t do a thing he wants to. He’s got to take orders for everything. We might as well be in Europe.”

“I met Mrs. Joruska on the street,” said Mrs. Boyd. “When I said the same thing, she said they lived like this

for eleven years

in the old country.”

“And here we are complaining,” said Mrs. Graham, “when with us it will be only a few weeks. I’m ashamed of myself.”

“It’s always like this after a flood, isn’t it, Mother?” asked Sally. “Remember those floods in the Ohio River? And last year there was a bad one out in Iowa. I saw it on television.”

“We have not suffered at all,” said Mrs. Graham briskly. “Only those who lost dear ones and their homes, like the Webbs and the Dillons, know.”

“Jim says that as soon as the town gets electricity, the stores will open from six to eight in the evening,” said Mrs. Boyd. “This will allow the big trucks and bulldozers to work by day without people and traffic on the streets. After that, things will be better.”

It was a happy day for all in the Boyd house, when Mr. Graham returned with a three-burner kerosene stove and several jugs of oil. He also brought a crate of eggs. The women made coffee all day long. Mrs. Nelson fried eggs on demand. Several Army men, working on bulldozers removing the debris of River Bend, stopped in now and then for food and drink.

Once after they left, Ronnie said, “That skinny guy ate twelve eggs! I counted them!”

“He must have been hungry,” said Barbara.

They all laughed.

After new food supplies were brought to the Town Hall, Mrs. Graham spent one whole morning standing in line to get a piece of meat. And when she got it, it was a very tough piece of second-rate beef.

“Tough old cow that died in the flood!” said the boys.

But the women made a stew out of it, added canned vegetables, and everybody said it was the best meal they had ever eaten.

It was

meat

and it was

hot!

NEW CLOTHES

“W

E MUST GET SOME

new clothes,” said Mrs. Graham.

“But how can we with the stores all closed?” asked Sally.

“We’ll go to the Town Hall and see what they have,” said her mother. “If the clothes we are wearing get any dirtier, they will fall to pieces.”

“There is plenty of water now,” said Mrs. Boyd.

The fire department had run a water pipe down the highway to River Bend, on top of the ground. The city water was on again. People could attach their garden hose to the pipe and get water for cleaning, washing or scrubbing. But still there was no electricity. Clothes had to be washed by hand.

“Gee! I’m sure glad to go somewhere once again,” said Bobby Graham.

After being cooped up for so long, it was exciting to get out. Going somewhere meant more than it ever had before. Mrs. Boyd brought her car, and Mrs. Graham and the children got in. Barbara went along too.

“I’ll tell you what I need, Mother,” said Bobby. “Shoes and sweater and pants and underwear!”

“Is that all?” Mrs. Graham laughed.

“It’ll do for a while,” said Bobby.

Mrs. Graham turned to Karen. “Do you have to take that doll wherever you go?”

Karen hugged the doll and smiled. “Yes, I have to,” she said. “Dolly wants to go too.”

It was a changed town through which they passed. Most of the houses on the river side of Farmington Avenue were gone. Their back yards were gone, too, only cellar holes were left. The bridge still stood across the river, but a great gully had been washed at its far end. Across the river, houses were gone too. In those that remained, clean-up work was going on. People were shoveling out mud. Trash and debris and mud were piled high along the sidewalks. Trees on what had once been a beautiful shaded street were upturned. Stores were boarded up where plate glass windows had been.

The children were silent as they looked. Not until now did the full significance of the tragedy reach them. Sally put her arm in her mother’s. “I can’t bear it,” she said.

“I never thought a flood could be like this,” said Barbara.

The Town Hall was a busy place. Above the door hung a huge sign: RED CROSS HEADQUARTERS. Cars were coming and going. People went in and out the door. The two women herded the children inside.

“Is this a store, Mother?” asked little Tim.

“No, it’s the Town Hall, silly,” said Jack.

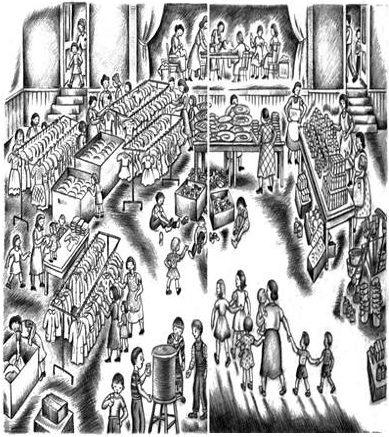

They entered the large auditorium. On the right side were tables piled high with food, boxes of cereal and canned goods, and milk in cardboard containers. On the floor near by was an array of brooms, mops, pails, sponges and disinfectants. Mrs. Graham picked some out to take home with her. “I’ll need them for cleaning up,” she said.

On the left side were lines of clothes racks, with clothes hanging on hangers. There were boxes with folded clothing and shoes near by. A table in the center of the room was piled high with sheets, pillow cases and blankets. On the stage, a group of women were sitting around a table, sewing and mending second-hand clothing. Clothing had been donated and shipped in from many parts of the United States.

Mrs. Boyd helped Mrs. Graham and a volunteer worker look for clothing and shoes for the younger children. Barbara helped Karen and Sally pick out slips and dresses, second-hand shoes and socks and some underwear.

“Now, let’s pick out yours,” said Sally.

“Oh, I’m not taking anything,” said Barbara.

“But they’re

free

, Barbara,” said Sally. “Look at this pretty blouse and skirt. It’s your size and your favorite color, blue.”

“Why don’t you take it, Barbara?” asked Karen. “You could pretend that all your clothes were lost in the flood.”

“I don’t need it,” said Barbara. “I have enough dresses.”

Sally looked at her friend in wonder. The volunteer worker said, “There are not many little girls like you. You’d be surprised how greedy people are. Most of them take all they can get, because it costs nothing.”

Sally put her arm around Barbara’s waist. She wished she could be as fine and good as Barbara, as thoughtful and kind.

Karen looked up at the young woman. “Can I get a dress for my doll?” she asked.

“Why yes,” said the woman. She brought baby clothes and Karen chose a pink dress. She put it on her doll and thanked the woman.

“Look!” cried Barbara. “There’s the Marciano girls. Let’s go talk to them.”

Angela Marciano came in the front door, holding her little sister Linda by the hand.

“Hi, there, Angela!” called Barbara. She and Karen and Sally went over.

“Hi!” said Angela. “What you girls doin’ here? Gettin’ new clothes to wear?”

“Yes,” said Sally, “a few. Mine are still at home and we can’t get to them.”

“You getting something, Angela?” asked Barbara.

“Oh, we been here lotta times,” said Angela, “and got a whole bunch of things. We got clothes for all of us and stuff to eat. We got a dollhouse for me and Linda—Linda lets me play with it sometimes. We got games for Tony and Al. And what do you think? We got our pictures taken three times!

They’re gonna be in a magazine!”

Sally could only think of that sad day in school when Linda was missing. Now, a changed Angela was talking. And little rescued Linda was being terribly spoiled.

“Tell them what you did, Linda,” bragged Angela.

“I was on TV in Hartford,” said Linda, proudly. “I told ’em I stayed all night in a tree with my dog Tiny.”

“Everybody thinks my little sister is wonderful,” Angela went on. “We’ve got a rent and the Red Cross is giving us all new furniture, beds, blankets, silverware and tables and a beautiful red chair to go good with our new green rug! Gee! There’s my mother. We gotta go.”

Barbara and Karen laughed happily over the good fortune of the Marcianos. They saw some of their school friends around the water cooler at the entrance. Several boys were getting drinks, while the girls waited their turn.

“There’s that mean old Tommy Dillon,” said Sally. “I thought the Dillons went to Vermont.”

“There’s David Joruska and Carol Rosansky,” said Barbara. “Let’s go over and talk to them.”