Flight 232: A Story of Disaster and Survival (32 page)

Read Flight 232: A Story of Disaster and Survival Online

Authors: Laurence Gonzales

Tags: #Transportation, #Aviation, #Commercial

In the hours after the crash, Chaplain Clapper

had stayed at headquarters, talking to rescuers and fire fighters and lending a sympathetic ear to anyone who needed it. He listened to a fire fighter tell of a woman he had found strapped into her seat, screaming. When he cut the seat belt, she fell apart. She was being held together by the seat belt. She died at his feet.

As evening came on, he decided that he needed to go home, clean up, and “put on my uniform so they could see the cross.” Clapper hiked out to the road and stuck out his thumb. He said, “It wasn’t hard getting a ride. I think people were in a helping mood that day.” At home, he indulged in a big hug from Jody. The girls were already in bed, but he went in and kissed Laura and Jenna anyway. They had enjoyed

Peter Pan

in the theater at the Southern Hills Mall. Then Clapper showered, put on his chaplain’s uniform, said good-bye to his wife, and drove back to the base.

“I spent that night walking around the perimeter.” He saw police, FBI agents, and fire fighters sitting out on their equipment watching for flare-ups from the wreck. The pools of yellow illumination from the lights somehow made the shadows seem that much deeper. As Clapper moved around in moonlight and arc light, he said, “I found that when you’re keeping vigil with the dead, sometimes it can be a very emotionally noisy space.” He would stop and chat with anyone who wanted to talk, “and they’d start telling me what they saw.” In many cases, the crash brought back old traumas. The cops talked about bad road accidents. The fire fighters talked about their worst fires. Clapper spent nearly two hours with one member of his Guard unit. The man needed to talk about a child he had lost. “We carry all of our brokenness and our tragedy with us,” Clapper said. “And when you open the door on tragedy, perhaps because a new tragedy has come into your life, all those old tragedies start spilling out.”

On through the night he wandered among the dead and their attendants. And as a gray light bled into the eastern sky, Clapper strolled with one of the security guards in quiet contemplation. After a time, they came upon a section of the plane where bodies still occupied some of the seats inside. And in the long cables of newborn sun from the east, “I could see something that made me cry.”

“Hey, Chaplain,” said the security guard. “Are you okay?”

Clapper later said, “I guess that was the most okay thing I could do was cry. I had seen this large man. And he was embracing a young boy. Both dead. And to me, to catch that vision of love even at the moment of death was very powerful.”

Once the sun had risen, Clapper went back to his office and slept on the floor for two hours. Then he splashed water on his face, found a cup of coffee, and went out to the ramp, where Air National Guard men and women and fire fighters were preparing with teams of pathologists, photographers, scribes, and volunteers to document and remove the dead. They were boarding pickup trucks for the ride out to site. Clapper climbed into the bed of one of the trucks and said, “Unless there’s some objection, I just want to have a word of prayer before we start this.” No one in the subdued and exhausted crowd objected. After a short prayer, Clapper began, “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures. He leadeth me beside the still waters. He restoreth my soul. He leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.” As he recited the twenty-third Psalm, he looked out over the crowd of workers and the destruction and chaos beyond, the torn metal, the scorched runways, and the rich land with all the people scattered there. And the chaplain saw, indeed, that “we were there, in the valley of the shadow of death.” His voice cracked during the recitation. At the time he was embarrassed, but later he said, “Maybe sometimes God’s word has to come through a cracking voice in this world.”

T

he

moon was still up

, pale in the western sky, as Robert MacIntosh, the investigator in charge, made his way to the first organizational meeting of the NTSB on Thursday morning, July 20, 1989. He estimated that in addition to the press, 130 people showed up at the conference room in the convention center downtown.

Daniel Murphy, the postmaster

, was among them. He wanted to be permitted onto the site so that his workers could collect the sacks of U.S. mail—nine hundred pounds of it—that were scattered across the airfield. Within thirty-six hours of the crash, all that mail would be delivered with notes signed by Murphy explaining the circumstances of the delay. In Montgomery County, Maryland, a high school teacher received an orchid that he had ordered from Hawaii. Like so many of the passengers, the flower was in perfect condition, although Murphy’s letter assured the teacher that it had been through the crash.

Much of the NTSB meeting that morning was taken up with assigning duties to members of the NTSB Go Team and then selecting representatives to work with whatever agencies or organizations were concerned. So, for example, the Engine Investigation Group for the NTSB was headed by Edward Wizniak, a senior aerospace engineer. General Electric was asked to provide representatives to work with him, and the obvious choice was William Thompson, the flight safety engineer who had arrived with the GE Go Team on the Lear jet the night before. Since the engine was the obvious suspect in the chain of events, GE provided nine engineers for the group. McDonnell Douglas and the FAA each contributed two more, while United Airlines sent one.

Wizniak, who was seventy-eight years old

when I interviewed him, could not remember the exact number of engineers who accompanied him when he left the convention center Thursday morning and drove out to the field for his first look at the number two engine, serial number 451-243. Thompson was there. He and Wizniak knew that the engine had fallen out of its mount upon impact and was lying to the east of Runway 4-22, on Taxiway Juliette just off the main ramp. The group drove through the gate and stopped at the Air National Guard headquarters, where they were shown the video of the crash. It was an unprecedented piece of evidence.

Then they drove to the northwest end of the ramp. They could see the engine even before they entered Taxiway Juliette. As they closed the distance, the engine looked worse and worse. Being the orderly and linear engineers they were, they decided to start at the beginning and work their way back. Thompson described it this way: “We also were interested in getting a general overall feeling for what had happened . . . and this included taking a walk to the impact initial touchdown site and, more or less, walking down the runway to the end near the empennage [tail] area.” Down the runway under the cool morning sun came the Engine Investigation Group, their heads full of engineering truths, as they attempted to wrest some orderly and analytical thoughts from the chaos before them. Even though what they really wanted to see was the number two engine, they encountered parts of the number three engine first and examined them. That engine appeared to have been running normally when the plane crashed. It had been wrecked by contact with the runway, on which its housing had left a series of symmetrical lens-shaped scuff marks. As they walked southwest, they encountered all manner of aircraft parts—flaps and wheels and rudders—among which lay the dead. At last they returned to Taxiway Juliette and the number two engine. “One of the first things that we noted,” said Thompson, “was the absence of the fan rotor . . .” He meant the seven-foot fan on the front of the engine, known as the number one fan. It was gone. “The forward fan shaft itself had been fractured, and there was a small stub area remaining, sticking out at the center of the engine in a forward direction.” The thrust reversers were banged open like a clam shell.

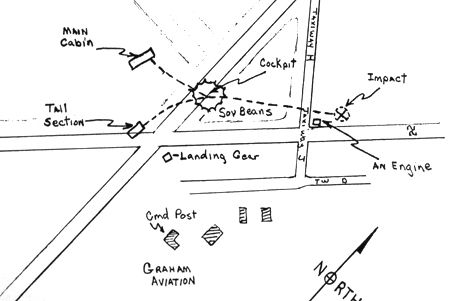

A sketch made during the investigation showing where various parts of 1819 Uniform came to rest. Engine number two lay on Taxiway Juliette.

From NTSB Docket 437

As Wizniak told me, “Walked up there, found the engine there, and looked—woah! Where’s the—? First thing you notice, boy, the whole front end of the engine is completely gone. And nearby was the fan containment ring.” Only half of it was present, the other half being in a cornfield about sixty miles away near Storm Lake, Iowa. That big hoop of stainless steel, which had encircled the front fan, was designed to stop a fan blade if one happened to be released. But said Wizniak, “You could see how it had split in half.” The entire mammoth number one fan disk had burst into two pieces, tearing the heavy steel containment right in half as fragments escaped. Many of the thirty-eight blades attached to that disk had presumably escaped too. Neither Wizniak nor Thompson had ever seen such a thing.

MacIntosh also viewed the containment ring that first day of the investigation. “Right away you know you’ve got a rotating parts failure,” he said. “Now, knowing

why

you had a fan disk rupture is the trick. And then trying to figure out how that damaged the aircraft to the degree that it did . . .” In fact, the damage to the engine was so severe, so unprecedented, that Thompson was moved to wonder if part of the cowling from the number one or number three engine had come off the plane for whatever reason and had then been sucked into the number two engine, destroying it.

As the giant fan disk split and broke through its metal containment, it left clear evidence of what had happened. Wizniak and Thompson could see “witness marks” across the surface of the containment ring, where the fan blades had made contact as “it just departed,” as Wizniak put it. They could also see that once the disk failed, it went through three-fourths of a revolution as it burst through that containment ring. Studying it in the July sunshine, Wizniak was shocked to see that one of those fragments comprised about two-thirds of the whole disk. He later described his reaction: “Oh, my God. Lord above. That is really an impressive sight. And kind of sad.” The engine towered above Wizniak, but even a tall man had to look up to examine it in the glaring light. He remembered saying out loud, “Oh, Lord, what happened there?” More than two decades later, he said, “The engine just tore it up and it was one big mess.”

But most importantly, as soon as he looked at the damage to the containment ring and realized that the main fan disk had come apart, “I already knew it was probably subsurface fatigue origin,” said Wizniak. He meant that he suspected that somewhere within the titanium disk that held those thirty-eight blades, a fatigue crack had originated in a flaw of some sort. “Yes,” he said, “that’s what happened. You knew it instantly.”

Thompson and a representative of United Airlines stood beside Wizniak, who later said, “They all had bad looks on their faces. It was a shock.”

Standing amid the wreckage, with the bodies still lying out in the sun, Wizniak’s mind was drawn to an Eastern Airlines L-1011, the direct competitor to the DC-10. Like the DC-10, the Lockheed Tri-Star jetliner had an engine on each wing and one through the tail. As with United Flight 232, Eastern Flight 935, out of Newark, New Jersey, experienced an explosion of the number two engine in the tail.

A bearing around the driveshaft was deprived of oil, and as Wizniak put it, “The fan shaft became ductile and it just let go.” The fan disk “just sort of walked out like a top. It’s somewhere out there in the Atlantic Ocean still.” The failure of the number two engine eliminated one hydraulic system. Fragments from the explosion penetrated the tail and cut the lines for two of the other hydraulic systems. “The fan disk came out and came within a hair’s breadth of cutting all the hydraulic lines.” The reason that November 309 Echo Alpha, the Eastern plane, was able to make an emergency landing at JFK International Airport on that September day in 1981 was that it had four hydraulic systems. McDonnell Douglas had designed the DC-10 with three.

Contemplating this possible scenario, Wizniak returned to Graham Aviation, where he called Washington. “And they couldn’t believe it,” he said. He told them that the number one fan disk had shattered and vanished from the number two engine. He ventured his opinion that the cause was a tiny defect that began the process of cracking the metal over a long period of time. He said that the disk had come out in two big pieces, “and they brought up all kinds of things, ‘You’re sure it wasn’t birds?’ ”

Even as late as the Saturday after the crash

, the

New York Times

was speculating that the crash may have been the result of birds being sucked into the engine. The disk, however, had exploded at thirty-seven thousand feet, an altitude to which even the most ambitious birds would not aspire. The people at NTSB in Washington asked Wizniak if it might have been blue ice, which refers to the blue fluid in the toilets. In the past that fluid (which had splashed all over Susan White at impact) had leaked out and frozen in the cold upper atmosphere. Chunks of it had broken off and been ingested by jet engines.

The speculations back at GE headquarters in Ohio were extensive as well.

John Moehring took charge

of the in-house investigation. He and his engineers set out all the scenarios they could conceive of to explain what had happened. Their first thought was what he called “a major ingestion event, or that something has happened to cause a very severe obstruction.” They considered whether the driveshaft itself could have failed or the bolts that held the disk to it. The driveshaft was a long tube that flared at the forward end into a cone. That funnel-shaped end was attached to the fan disk with twenty bolts. The engineers at GE evolved seven hypotheses to explain how the failure might have happened, and Moehring assigned a leader to each one. That leader pulled together a team of engineers that set to work trying to prove its chosen theme for explaining how the disk failed.

Christopher Glynn

, the manager of fan and compressor design at the GE jet engine plant in Evendale, Ohio, was assigned to lead the team devoted to proving that the “prime event in the sequence” was the fan disk itself, serial number 00385. He immediately began recruiting metallurgists, engineers, and “analytical people,” as he put it, to help demonstrate that the disk could have fragmented, starting the sequence of events that led to the loss of control and the crash. There could have been any number of causes for the disk to burst. On September 22, 1981, a turbine disk exploded on a DC-10 at Miami, Florida, because a mechanic had left something inside the engine while working on it.