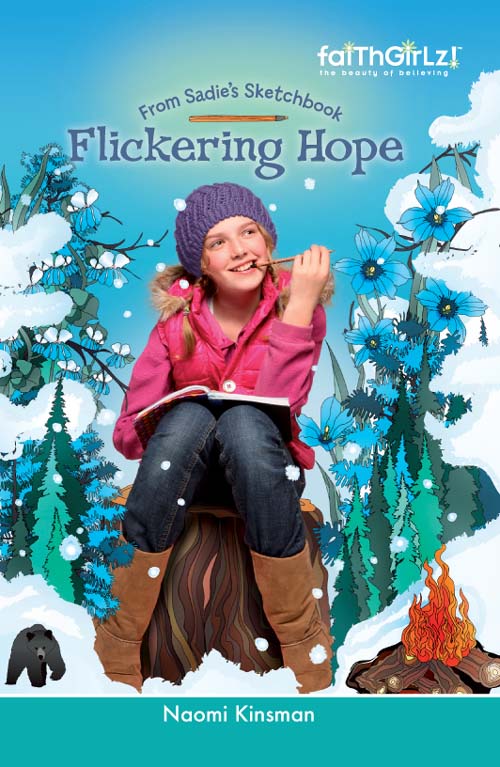

Flickering Hope

Authors: Naomi Kinsman

From Sadie’s Sketchbook

Flickering Hope

Book Two

Naomi Kinsman

For my parents, who taught me to believe in Christmas miracles, big and small.

Chapter 11: A Christmas: Project

Chapter 16: Words and Pictures

Chapter 18: Angels We Have Heard on High

Chapter 22: The Family: in the Woods

Chapter 29: We Wish You a : Merry Christmas

Pea-Soup Gravy

P

ots and pans and spilled spices filled the research cabin’s tiny kitchen. Pumpkin pies cooled on top of the washing machine. Turkey, bread, and mashed potatoes warmed in the oven. I brushed flour off Ruth’s nose and grinned at Andrew. He smiled his crooked half-smile and waved olive-topped fingers.

“No fair. We’re not done cooking!” I said.

“Olives are an appetizer, Sadie.” He brought the tray over. Ruth and I slipped olives onto our fingers, and I felt six years old instead of twelve. In the good way, the way you can only feel when you’re with friends you trust, and you’re all in it together. One by one, we popped olives into our mouths until our cheeks bulged. We laughed as we watched each other chew. Happiness fizzed through me, sweet and bubbly, like the sparkling apple cider chilling outside in the snow.

Andrew and I had spent almost all of November begging his mom, Helen, to host Thanksgiving dinner.

Helen had smoothed back the black wispy hairs that never failed to escape from her signature French braid. “We don’t have the space! It’s a research cabin, not a house.”

Still, she and Andrew lived here. One main room filled the cabin’s first floor, serving as kitchen, living room, and dining room, with Helen’s paper-strewn office in the back. Andrew and Helen’s rooms, the bathroom, and one guest room made up the second floor. The mudroom overflowed with boots, snowshoes, poles, and winter gear for trekking out into the woods and monitoring dens. Photographs of Helen’s research subjects, the now-hibernating bears, lined the log walls. Andrew and I had known Thanksgiving at the cabin would be messy and crowded and perfect. We had promised to help cook and do all the clean up, and even to snowshoe the four miles out and back to check on Patch’s den after dessert so Helen could have a true day off.

When my family moved to Michigan three months ago for the start of my seventh grade, I had pictured moments like this one—moments full of new friends and fun. You just can’t have a stuffy Thanksgiving dinner in a log cabin.

“Aha!” From the other side of the washing machine, Dad pulled his head out of the spice cabinet and did a victory dance, holding up a box of food coloring. Flour billowed off his sandyblonde hair. Somehow, he missed the cooking lesson in which they tell you not to run your fingers through your hair.

“We’ll dye the gravy!” he announced.

Mom and Helen looked up from their conversation. Mom hid her smile behind a mug of tea. The lines often so tight around her eyes were relaxed today, and color filled her cheeks.

Mom had refused to participate in gravy-making. She baked the pies and mashed the potatoes but drew the line on gravy, which never came out right for her anyway. Helen had poured turkey juice into the pot and added spices and cornstarch. Still, the gravy was too soupy. Dad stepped in, but his excessive use of flour turned the gravy white.

As he passed me the food coloring, Dad said, “Come on, Sadie, put those art lessons to use. No one wants to eat ghostly gravy.”

Ruth and I squeezed red and yellow and blue and green drops into the pot and stirred. Higgins jumped up, muddying the cupboard door with his too big puppy paws.

I pushed Higgins away. “Down, Higgy!”

Of course he jumped back up, his brown ears flopping and his rope-like tail thwapping our legs. Dad and Andrew supervised the color-mixing over our shoulders. When I squeezed the final yellow drop into the gravy and all the coloring was used up, we stepped back.

Andrew nodded, a very serious look on his face. “Much better.”

We dissolved into laughter. The gravy was pea-soup green.

As Andrew set the gravy boat out on the counter, Ruth’s family plowed up the snowy driveway in their SUV. Her parents stomped snow off their boots in the entryway and untangled

themselves from coats and hats and mittens, while her twin brother and sister circled them in a left-over game of tag.

“Happy Thanksgiving!” Ruth’s dad said. “We had twenty people at our last service this afternoon. Everyone came to church early so they could hurry home to feast.”

“You’re just in time.” Helen hugged Ruth’s parents and the twins, who stood as still as could be expected. “Make yourselves at home.”

We arranged plates and silverware and hot platters of food on the countertop, buffet style.

“Rick, will you say a blessing?” Helen asked Ruth’s dad. “As our resident preacher?”

I was surprised. Helen never went to church, and I didn’t think she prayed over meals. But maybe Thanksgiving was different. After an awkward moment of people first closing their eyes, then bowing their heads, then looking around and closing their eyes again, the rustling settled.

“God, thank you for the joy of an afternoon with family and friends. Thank you for this abundance of food and for the many blessings you’ve brought this year—health and safety and peace. Help us be a blessing to one another. Amen.”

As we opened our eyes, I watched Mom turn to kiss Dad on the cheek. Could Mom finally become healthy?

Please let it be possible.

I piled my plate with mashed potatoes and jello salad and took the smallest possible piece of turkey, which I’d pass off to Higgins when no one was looking.

Andrew, Ruth, and I sat on the couch. The twins sat at the table, because the table only seated four, the extra adults perched around the living room and kitchen with their plates.

I shoved my mashed potatoes to the far side of my plate so the melting jello wouldn’t contaminate them.

“So how’s the food-fight queen? Is Frankie back yet?” Andrew kept his voice low.

None of us wanted to launch the adults onto the topic of hunters, or specifically, Frankie’s hunter-dad Jim who had it in for Patch.

Ruth swirled gravy into her mashed potatoes, turning the entire lump green. “It’s been two weeks, so maybe she’s not coming back.”

“I’m worried,” I said. “It doesn’t seem like her friends know where she went.”

“Come on, Sadie. She calls you Zitzie. You can’t really miss her,” Ruth said.

I pushed Higgins away from Ruth’s plate. “Frankie only called me Zitzie when I had all those mosquito bites.”

“If something was truly wrong, we’d have heard,” Andrew said.

We dug into our food, relieved when the twins finished eating and chased Higgins around the living room, so we no longer had to defend our plates from dog-slobber.

“Dessert now or after the hike?” Andrew asked.

Ruth grabbed our plates. “Now. And maybe afterwards, too.”

I helped load the dishwasher while Andrew glopped mounds of whipped cream onto each piece of pie. Mom had made her famous praline crust. We settled back onto the couch, and I took a slow bite, letting the brown sugar and butter melt on my tongue.

“That’s it. Next year, we’re doing Thanksgiving exactly like this.” Ruth stopped, her fork halfway to her mouth. “You’ll be here next year, right Sadie?”

I shrugged. “I don’t know how long the Department of Natural Resources will need Dad.”

“At least through hunting season next fall,” Andrew said. “Things heat up when the bears come out of hibernation. The DNR will need him to mediate then.”

I nodded, but even the familiar, comforting taste of Mom’s pumpkin pie couldn’t take away the uneasiness that slithered into my stomach. This was home now. I didn’t want to pick up and start again, especially now that I understood how hard starting over could be.

I ate my last bite of pie slowly, savoring it, and then said, “Let’s go hike. Before my stomach explodes.”

“Stick to the path,” Helen called from the table. “And make sure you cover up your tracks close to the den, Andrew. The whole point is keeping Patch safe.”

Andrew rolled his eyes. “Yes, I know, Mom.”

But Andrew worried about Patch just as much as his mom did, especially now, after he and I had overheard Frankie’s dad, Jim, threaten to find Patch in her den. Now, more than ever, Patch needed our help.

Snow Quiet

U

pstairs in the guest room, Ruth and I yanked and pulled and zipped ourselves into our gear. Ruth and Andrew always expected me to dress wrong for the weather, being from California. But my family had skied in Tahoe almost every year, so I knew how to dress for cold.

I caught our reflection in the mirror — Ruth, tiny, swallowed up in her red ski coat and pants, her black hair entirely hidden under her striped red hat, and me, looking like the Jolly Green Giant in my lime green coat and dark green pants. I was a normal height for my age, but next to Ruth, I looked enormous. As usual, curly hair escaped my braids in every direction. We’d struck a deal about this, my hair and I. Each morning, wet and well-behaved, my hair allowed itself to be woven into braids,

which artfully decomposed through the day into a mess that, at least, didn’t resemble bed-head.

I pulled on the purple stocking cap topped with a fuzz ball that Pippa, my best friend from California, had sent me as a first-snow present. Ruth and I waddled out into the hall. Andrew came out of his room and slammed the door behind him.

“What? Is your room a

total

mess again?”

Andrew thought a few misplaced papers was a catastrophe.

“No.” Andrew blocked my way.

I dodged past and pretended to turn the doorknob. “You sure?”

He yanked my hand away. “Knock it off.”

“What if we already peeked in?” I grinned at him. “When we first came upstairs.”

Andrew frowned, his eyebrows scrunching together. “Did you?”

“Maybe.”

“No really, Sadie, did you?”

His mouth pressed into a tight line and real anger flashed in his eyes. Normally teasing was no big deal for Andrew.

I raised my hands in mock surrender. “Kidding, Andrew. No big deal.”

He didn’t smile. When I stepped back, he walked wordlessly away. Ruth raised an eyebrow at me. I shrugged, laced my arm through hers, and we followed Andrew downstairs.

We sat on the edge of the deck to strap on our enormous snowshoes. I had never worn snowshoes before, but I wasn’t about

to tell that to Ruth, or Andrew, especially after his freak-out upstairs.

I stood, took one step, and tumbled into a snowdrift. Ruth snorted and burst into giggles.

“Last one to the trees has to scrub the turkey pan!” Andrew called, tramping out into the knee-deep snow as though walking on a perfectly groomed trail.

I brushed white powder off my gloves and shook it out of my hair. “Cheater!”

When I took another step, I almost fell again. Ruth caught me on the way down and yanked me upright.

“You have to bend your knees,” Ruth said.

I swung one foot up and over the snow and transferred my weight, finally getting the swing-stomp by the time we reached the trees.

Andrew’s red hat bobbled up and down in the distance. Ruth and I moved in rhythm, avoiding snow that fell off the pine needles above in icy glops.

I wrapped my scarf tight so the wetness couldn’t slip down my back. “What was that all about? Do you think Andrew’s hiding something? A picture of a girl he likes or …?”

Ruth raised an eyebrow at me. “No way, Sadie.”

I didn’t want Andrew to have a picture of another girl in his room. And I didn’t want to consider why Andrew’s secret was so important to me.

I tried to decide which would feel better—falling face-first into the snowbank to cool down my burning cheeks,

or screaming as loud as I could—when suddenly Ruth held out her arm, blocking my path. “Look.”

We stepped out of the trees into a meadow. Aside from Andrew’s tracks, the unmarked snow stretched to the distant trees from our right to left. We stood listening to the snow quiet.

“Do you ever feel like you could just turn a corner and step into Narnia?” Ruth asked. “Like … anything is possible?”

Ruth looked out at the snow, her face lit up, almost glowing. Was anything possible? Could Andrew … Even the first few words of that thought made me want to run. Andrew was my friend, and hoping for more would ruin everything. I took a deep breath and wiggled around so thoughts of Andrew would disappear from my mind. He wasn’t the only impossibility in my life.

Mom. Every disease I knew of, even the bad ones like cancer, had treatments. But somehow Mom had been cursed with a disease with no treatment. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, a disease doctors couldn’t understand, couldn’t predict. Instead of fixing her, they suggested experiments. Try vitamins. Try rest. Lower your stress level. Exercise. Don’t exercise. Still, exhaustion crept up on Mom, pounced on her when we least expected it, ruined birthdays, holidays, vacations. Good days when Mom was finally present, free from the monster inside her, only reminded me of what I missed the rest of the time. And good days could end any second.

Ruth stood still, her long lashes dusted with snowflakes. Sometimes I wanted to tell Ruth everything, about Mom, about my questions, about me. I wanted to turn myself inside out and show her and see if I was okay. Pippa knew many of my secrets, not because I had chosen to share them, but because she had experienced most of them right along with me. Ruth was different. She only knew the parts of me I chose to share.

I stood right on the edge, wondering if I should step over.

Ruth grabbed my elbow, interrupting my thoughts. “We’ve got to catch Andrew. Up there, no one has made a single track. Think of how amazing it must look.”

She took off faster than I imagined snowshoes could ever go. I stumbled through the snow after her, fell on my knees, and pulled myself back up, laughing the whole time. Steam billowed out of the neck of my coat. I took it off and tied it around my waist, still walk-running to keep up with Ruth.

We plunged back into the trees, following Andrew’s tracks. Finally, we saw his red hat.

“Andrew, wait up!” Ruth called.

When we caught up with Andrew, he led us off to our right. “The den is up this hill. Walk quietly now and muss your tracks.”

We zigzagged between trees to disguise our path. About a hundred feet away from the hillside where Patch had dug out her den under a rock, we stopped. I could barely see the exposed part of her black, furry back, almost entirely covered with snow. She and her yearlings had filled most of the gap with dirt and leaves after they had climbed into their den, a process which Andrew and I, amazingly, watched over a month ago.

A small section of the gap was still open for air circulation. For a long moment, we watched snowflakes fall on Patch’s black fur, and then we backed away from the den.

A safe distance away, Andrew said, “If only we knew the bears will be safe all winter.”

I nodded, not able to put my similar wish into words that expressed just how much I hoped for Patch’s safety. I slowed my pace, listening to snow melting and dripping off the pine needles. Then, I stopped, hearing a noise behind me. Rustling in the bushes. I listened.

Nothing happened.

I walked toward the bushes and crouched down to peer into the snow-covered pines. Two huge green eyes stared back at me.

At first, I couldn’t breathe. The small girl, who couldn’t be much older than Ruth’s brother and sister, held her finger to her lips. “Don’t let them see me.”

Words caught in my throat. What could I say to this dirt-streaked little girl? What was she doing out here, alone in the forest, in the vicinity of Patch’s den?

As I turned to check if Ruth and Andrew had seen, the girl gripped my arm with freezing-cold fingers, so cold I could feel the chill through my thermal shirt. “Promise you won’t tell anyone about us living out here.”

My mind spun. This little girl lived out here? With who? Why? How did they keep warm? When I didn’t speak, the girl squeezed tighter, her fingers surprisingly strong.

“Promise, or I’ll tell my dad the bears are near here.”

Her narrowed eyes and fierce grip told me this wasn’t an empty threat. Without meaning to, we had led her straight to Patch’s den. The girl shook my arm again, demanding a response.

The words slipped out of my mouth before I could stop them. “I promise.”

The girl took off through the snow, as fast as she could in her worn boots. Long, tangled brown hair swung across her back.

“Hey!” Andrew called out behind me.

The girl turned back, saw Andrew and Ruth, and glared at me, a warning clear in her eyes. But what warning? Haze filled my mind, as though I’d woken from a deep sleep. Broken bits of our conversation ricocheted off one another, making less sense the more I thought about them.

“What did she say to you?” Andrew put his hand on my shoulder. “Sadie?”

I realized I was cradling my arm, staring down at the muddy stains the girl’s fingers had left behind. The girl had almost disappeared into the trees.

“We have to follow her,” I said.

Our snowshoes made it almost impossible to run, but we stumbled forward as fast as we could, managing to keep the girl in sight, though just barely. When we stepped through the thick bushes into a clearing, Andrew held out his hand to stop us. A wooden shack slumped in the distance. Smoke rose from a metal pipe stuck at an angle in the roof.

We leapt behind the bushes as the shack door swung open, and a man in a flannel shirt, orange hunting vest, and knee-high boots stepped out into the snow. Behind him, a woman stood, concern clear on her face. She cradled a baby against her shoulder.

“Where’ve you been?” the man asked. “You left for the outhouse fifteen minutes ago.”

The baby whimpered, and the woman stepped back as the man laid his arm protectively across the little girl’s shoulders and led her inside. He closed the door, rattling the shotgun that leaned up against the cabin steps.