Flags of Our Fathers (9 page)

Read Flags of Our Fathers Online

Authors: James Bradley,Ron Powers

Tags: #Biography, #History, #Non-Fiction, #War

Mike Strank was nineteen now. The year was 1939. In Europe, Hitler’s legions were overrunning his Czech homeland, making slaves of his people.

Mike decided to join the Marines.

He didn’t have to do it. He could have avoided military service altogether, given his Czech citizenship. Brother John always puzzled over the fact that the Marines allowed him in at all: Apparently, no one checked out his nationality.

Mike enlisted on October 6, 1939. He was the only one of the six flagraisers to sign up before America entered the war. But soon the brainy Czech boy would transform himself into a prototype American fighting man: a tough, driven, and consummate leader, advancing without complaint toward what he came to understand was his certain death.

Three

AMERICA’S WAR

What kind of people do they think we are? Is it possible they do not realize that we shall never cease to persevere against them until they have been taught a lesson which they and the world will never forget?

—

WINSTON CHURCHILL, ON THE JAPANESE,

1942

WHEN IT STRUCK, it must have seemed a plot twist out of some futuristic movie, but this time for real.

A sleepy American Sunday afternoon in early December, Yuletide season in the air, roast chicken dinners finished, and the dishes washed, family radios tuned to Sammy Kaye’s

Sunday Serenade

on the NBC Red Network, or a

Great Plays

presentation of

The Inspector General

on the Blue, or perhaps the pro football game between the Washington Redskins and the Philadelphia Eagles…

And then suddenly urgent bulletins crackling through static. The future had begun.

The shocking interruptions started at 2:25

P.M.

John Daly of the NBC Red was on the air first:

“The Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, by air!”

Five minutes later an anonymous announcer elaborated over both NBC systems:

From the NBC newsroom in New York! President Roosevelt said in a statement today that the Japanese have attacked the Pearl Harbor…Hawaii from the air! I’ll repeat that…President Roosevelt says that the Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii from the air. This bulletin came to you from the NBC newsroom in New York.

As the afternoon wore on, the bulletins multiplied and a vast radio audience built: as many as eighty million listeners by one estimate. Some of them heard an anonymous announcer describing the tumultuous damage by telephone from the roof of radio station KGU in Honolulu. After a bomb narrowly missed the broadcast tower the man screamed:

“This is no joke! This is real war!”

The following day, most of those same listeners, including hundreds of thousands of children, tuned in again to hear President Franklin Roosevelt intone the six-and-a-half-minute speech whose key phrases would resound in American folklore:

Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan…

With confidence in our armed forces, with the unbounding determination of our people, we will gain the inevitable triumph, so help us God!

No joke. The real thing.

Before Pearl Harbor America had looked across the Atlantic for an enemy. Adolf Hitler was the enemy we feared and Japan was dismissed as only a threat. But after the “day of infamy,” newspaper maps of the Pacific and Asia were scrutinized at the kitchen tables of America.

Now America was in a World War, a “two-ocean war.” Across the Atlantic, in Europe, the U.S. would be fighting in support of and with an allied force. But for years, Russian, English, and French troops would do most of the fighting and take the brunt of the beating. And it would be Stalin’s troops who would really beat Hitler: seventy-five percent of the German troops who died fighting in World War II were killed by Russian troops.

Against Japan, however, America would stand virtually alone in the Pacific. Japan had violated American soil, and the first and last American battles of World War II would be fought there. The Pacific War would be “America’s War.”

America went to war in 1941. The Europeans had been fighting since 1939. But for millions of Asians, World War II had begun a decade before, in 1931.

Earlier in the century, Japanese civilians had lost control of the government to the military. Intent on making Japan into a world power, the military became preoccupied with Japan’s one glaring weakness: Japan had almost no natural resources, and its industrial base was at the mercy of imports whose supply lines could be cut. Japan, they argued, had to acquire a secure resource base to guarantee its industrial security.

To the military, this goal was important enough to alter the very structure of Japanese society. The entire nation had to be militarized for the goal, and military thinking and training were imposed on each citizen.

The military squeezed the Japanese populace in an iron vise. On one side was a militarized educational system that prohibited free thought. Schools became boot camps complete with military language and physical discipline. Youth magazines carried jingoistic articles such as “The Future War between Japan and America.” The final examination at the Maebashi middle school in March of 1941 required the students to discuss the necessity for overseas expansion. “It was commonplace for teachers to behave like sadistic drill sergeants, slapping children across the cheeks, hitting them with their fists, or bludgeoning them with bamboo or wooden swords. Students were forced to hold heavy objects, sit on their knees, stand barefoot in the snow, or run around the playground until they collapsed from exhaustion.”

The other side of the vise was a regimen of draconian “thought control” laws that constrained all civilians. Imprisonment and torture were the fates of anyone who questioned authority.

Using the deceptively neutral term “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,” Japanese propaganda claimed that Japan’s aim was to free its neighbors from white colonial rule. Instead, Japan, like Nazi Germany, used a master-race mentality and a highly mechanized war machine to subjugate those it claimed to be freeing.

Tokyo enslaved “those peoples who lacked the capacity for independence,” and stole their national resources. The Japanese attitude of superiority is evident in a document from the Imperial Rule Assistance Association entitled “Basic Concepts of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere”: “Although we use the expression ‘Asian Cooperation,’ this by no means ignores the fact that Japan was created by the Gods or posits an automatic racial equality.”

The nation “created by the Gods” initiated “co-prosperity” by raining terror down on Manchuria and China. With official approval and chilly detachment the Japanese army bombed Chinese cities and slaughtered everyone in its way, including unarmed men, women, and children.

Japan’s first conquest was Manchuria in 1931. Then, to consolidate control of Manchuria, Japan attacked China in 1937.

The Japanese army employed ruthless tactics in China. Japanese airplanes bombed defenseless civilians. Rats infected with deadly bacteria were systematically released among the populace, making Japan the only combatant to use biological warfare in World War II. The Japanese army raped and pillaged with full encouragement from its superiors. But China is a vast country, and despite millions of casualties, Japan’s war became a debilitating war of attrition.

And Japan’s relations with China’s allies, especially the U.S., became strained. Then, in 1939, war in Europe appeared to offer Japan a fortuitous way out of its dilemma.

Awed by the German blitzkrieg into France in May of 1940, Japan pushed into French Indochina. Japan’s military leaders calculated that Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941 would be successful. They argued that now was the time to capture other resource-rich Asian countries. Japanese militarists reasoned that the U.S. and the U.K. would be preoccupied by the German thrust and would not dare to allocate large military resources to Asia. Hawks argued that the American public would not support a long war far from its shores. A slowly tightening American economic boycott of critical exports to Japan hastened the decision to act.

Japan’s principal war aim was the conquest of European colonial empires in Asia. These empires would give Japan the resources it needed, and fostered a hope that a surrounded China would capitulate.

With a thoroughly militarized citizenry, an experienced army, and an immense navy, Japan was confident it could control the Pacific as its sphere of influence.

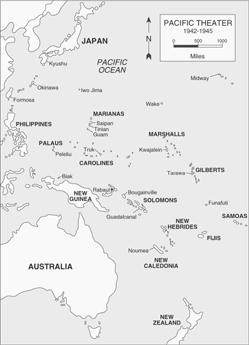

After disabling the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces thrust southward toward Australia, overrunning Wake Island, Malaya, Singapore, the Philippines, and what is now Indonesia. Japanese forces soon controlled the Pacific battlefield. Only Australia in the south remained unconquered.

The Japanese army had even humbled the United States Army. On December 7, hours after hearing the news from Hawaii, General Douglas MacArthur sat in the Philippines, stunned, seemingly unable to give a command to mobilize the largest fleet of warplanes in the South Pacific. When nearly two hundred Japanese bombers arrived over Manila, ten hours after the Pearl Harbor attack, they simply obliterated this fleet, which sat in convenient clusters on the tarmac.

MacArthur was soon forced to withdraw 65,000 Filipinos and 15,000 American troops from a defense of Luzon and into the mountains of the Bataan peninsula. They retreated in the face of a converging Japanese naval and infantry force. President Roosevelt, realizing the Bataan defenders were doomed, ordered MacArthur, America’s most decorated soldier of World War I, to flee by boat to Australia under cover of darkness.

“The battling bastards of Bataan,” as the trapped troops styled themselves, held out, starving, until April 3, 1942—Good Friday. They surrendered, the most crushing defeat in American military history. The emaciated survivors were driven sixty-five miles on foot for three days in lacerating heat to a prison camp: the infamous Bataan Death March. Some 15,000 prisoners perished en route. They succumbed to thirst, starvation, exposure, and the merciless abuse of the Japanese soldiers, who whipped, beat, and shot those who stumbled or paused to lap at water in some roadside stream.

But if the men in charge of America’s Pacific forces were temporarily stunned by the onslaught, America’s boys were spoiling for vengeance.

Robert Leader, who later served with John Bradley in Easy Company, recalled his youthful indignation on that shocking Sunday afternoon: “We were

so mad

at the Japanese for bombing Pearl Harbor. They bombed on a Sunday, we went to school on Monday and they piped in President Roosevelt’s ‘Date of Infamy’ speech. A bunch of us boys got together and said, ‘Let’s join up!’” He added, “I was never interested in killing people, but I believed that our country had been violated.”

Hundreds of thousands of his contemporaries believed likewise.

Enlistment centers were overwhelmed by the flood of eager enlistees. The entire nation, in fact, seemed overnight to have snapped out of its Depression-era lethargy. Everyone scrambled to be of help. Rubber was needed for the war effort, and gasoline, and metal. A women’s basketball game at Northwestern University was stopped so that the referee and all ten players could scour the floor for a lost bobby pin. Americans pitched in to support strict rationing programs and their boys turned out as volunteers in various collection “drives.” Soon butter and milk were restricted along with canned goods and meat. Shoes became scarce, and paper, and silk. People grew “victory gardens” and drove at the gas-saving “victory speed” of thirty-five miles an hour. “Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without” became a popular slogan. Air-raid sirens and blackouts were scrupulously obeyed. America sacrificed.