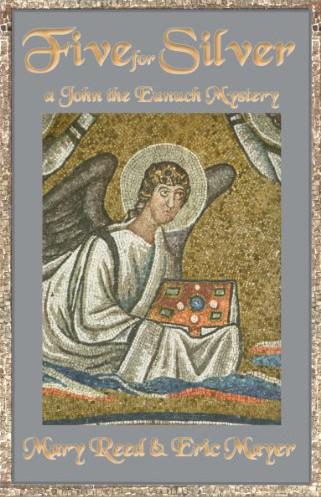

Five for Silver: A John, the Lord Chamberlain Mystery

Read Five for Silver: A John, the Lord Chamberlain Mystery Online

Authors: Mary Reed,Eric Mayer

Tags: #Historical, #FICTION, #Mystery & Detective, #General

Five for Silver

Copyright © 2003 by Mary Reed & Eric Mayer

First Edition 2003

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2003115435

ISBN: 1-5905-8112-1

ISBN: 978-1-61595-170-3 Epub

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

For our siblings

Contents

The young man awoke in the embrace of a suffocating nightmare.

To darkness.

A monstrous heaviness bore in on him from above and all sides.

He tried to move. His foot came down on a surface which resisted for an instant, then gave way. Wetness trickled into his boot. The invisible mass pinning him shifted with a soughing noise and the weight of the world settled onto his chest. What felt like an elbow or knee dug into the small of his back.

His eyes were open, but he could see only those ghostly lights that drift beneath closed eyelids.

He couldn’t breathe. He struggled to turn his head, to find air. His cheek was brushed by cold, stiff fingers.

Then he understood.

He was buried with the dead.

The miasma of death filled his nostrils, flooded his lungs. He tried to cry out for help, but could only manage to spit up a choking sob. In the blackness, his flailing hand encountered the rounded shape of a skull.

More than once as he had walked through the city he had stepped into the street, fastidiously distancing himself from a corpse sprawled beneath a colonnade or crumpled in a doorway. Here the dead pressed themselves against him with obscene intimacy, as if he were already one of them.

Perhaps he was.

From above, from the world of the living, came a muffled shout.

“Lies! More lies!”

A cascade of liquid trickled across his back. Blood?

No. Rivulets of fire, burning like hot coals. He must be alive. An incorporeal shade could never feel such blistering agony.

“Lye. More lye,” the shouter somewhere beyond the darkness repeated.

The young man clenched his fists, arched his back, and began to fight his way up toward air. He scrabbled higher, pushing with his feet wherever he could find purchase on a head or shoulder blade, pulling himself up through the nightmare of tangled limbs.

His hands slid against liquescent flesh, boiled off bones by lye poured endlessly into the heaped corpses. Was he at the bottom of a pit, or in one of the towers that Justinian had ordered be filled with Constantinople’s dead? Clutching at the darkness his hand fastened unexpectedly on a face.

He gagged convulsively.

For a heartbeat he lay still. The blazing fire inside his chest was as intense as that outside. Had he swallowed lye?

Ignoring the pain, he snaked one hand upwards and grabbed a cold, rigid arm. Once it might have been part of a prosperous merchant, a starving beggar, a Christian, a pagan.

To the young man, it was just another rung on the ladder back to life.

He forced himself on, pulling, slithering, pushing with feet and elbows.

A lifetime passed. Then, abruptly, he could see the vaguest wash of light, the merest suggestion of shapes.

He lunged upwards. A hand reached down. He grasped it.

Decayed flesh slid off the bone.

A final spasm propelled him into light. He saw then that he held a ragged strip of skin entangled with a silver ring, the gift of the pit.

“I’m alive!” he screamed as he looked up, just in time to receive a bucket of lye in the face.

John, Lord Chamberlain to Emperor Justinian, followed the physician Gaius through the crowded corridors of Samsun’s Hospice.

John was there because his elderly servant Peter had experienced a vision.

Gaius, a stout, balding man, plowed ahead, more than once treading on outstretched limbs and sprawled bodies. John picked his way more carefully, but could not prevent the gold-embroidered hem of his heavy blue robe from brushing against the sick who overflowed from crowded rooms into the hallways.

It made him uneasy because it seemed disrespectful. Many of Gaius’ patients were in their final hours; their surroundings were insult enough. For lack of sufficient pallets, the hospice corridors had simply been strewn with straw. The sooty plastered walls displayed crosses at frequent intervals.

John remarked on this to Gaius.

“Many take comfort from them,” he replied. “Why anyone should find comfort in a depiction of suffering is beyond my learning. Perhaps it reminds them their ills could be even worse? Then too, some rely on charms and amulets for protection against the plague.”

Such beliefs puzzled John as well. Like Gaius, he was a Mithran, among the few who clung to an ancient, pagan religion. It was an allegiance which could never be spoken aloud in the court of the Christian emperor.

“Tell me about this vision, John,” Gaius continued. “Why did Peter suppose it was anything more than a dream?”

“Because he was wide awake when the angel appeared.”

“But an angel? Surely that proves it was a dream? And how did he know it was an angel? What does an angel look like?”

“A man, apparently, with a glowing visage and surrounded by radiance. Peter said he had already put out the lamp and shuttered the window, and yet, when the angel appeared at the foot of his bed, he could clearly see the night soil pot in the far corner.”

“I’d be interested in a close look at an angel, but then I doubt a specimen will ever turn up in our mortuary.” Gaius sounded wistful.

They turned down another corridor more congested with patients than the last. Most of the sufferers displayed the grotesque swellings and black, gangrenous carbuncles characteristic of plague.

John avoided staring at the sick, but he could not shut out the sounds of suffering that came from every direction. Soft whimpers and moans, wracking sobs and screams filled the air. Occasionally he could make out muttered prayers, hoarse curses. If one did not listen too attentively, the cacophony merged into an almost soothing susurration akin to waves breaking against a rocky shore.

“In what language do angels converse, John? Greek? Or are they Latin speakers like the emperor? Not to say that an angel might speak any language we would know. How many is it you command? Four? Or perhaps is it more a matter of which tongue they choose to use?”

“You’d be an excellent theologian, Gaius. However, according to Peter the angel did not use any particular language. Peter was so amazed, he mentioned that specifically more than once. As he described it, the words formed in his head without his strange visitor making a sound.”

“And what words are sufficient to bring the Lord Chamberlain into a place full of the pestilence?”

“‘Gregory. Murder. Justice.’”

“It sounds as if you believe this strange tale.”

“What matters is that Peter believes it. I’ve rarely seen him so agitated.”

Gaius’ broad forehead wrinkled. He began to speak, then paused. “Do you know this Gregory?”

“Only by sight. Occasionally he came to meet Peter at my house, but he’s never entered it so far as I know. They’ve been meeting every week since Peter’s been in my employ and perhaps before then too. A few days ago, Gregory failed to appear at the Forum Constantine as they’d arranged.”

“So he is an old friend of Peter’s. Do you know anything else about the man?”

“I gather he and Peter served in the army together years ago. It’s my belief that Gregory hasn’t fared well since those days. I’ve noticed the evening before these visits, Peter always seems to find stale honey cakes or moldy bread unfit for a Lord Chamberlain to consume, as he puts it.” A brief smile illuminated John’s lean face. “He asks my permission to take these scraps with him to give to Gregory, rather than just throw them away. Naturally I always say yes.”

Gaius laughed. “I wouldn’t want your job, John, serving both an emperor and an elderly cook.” He stopped at an half-open door at the end of the hallway. “We’ve turned the old cistern beneath the hospice into a mortuary.”

John found himself studying his friend closer. When had Gaius gained so much in girth? The physician had always been stout. Now he looked obese, his stride laborious. He had obviously resumed his worship of Bacchus. Yet could anyone blame him, given the terrible scenes the man witnessed every hour spent at the hospice, ministering to patients who persisted in dying in horrible agonies, no matter how much Gaius and his colleagues labored to save them?

“You’ve been examining me ever since you arrived, John,” Gaius said in an irritated tone. “Do you think I haven’t noticed? Don’t worry, I haven’t caught the plague. There’s no danger from working with my patients so far as I can tell. In fact, we don’t even known how the illness is contracted. It seems entirely capricious. We see carters bringing the sick here day after day and they stay perfectly healthy, even though the rest of the time they’re hauling the remains of cautious folks found rotting away behind locked doors and boarded windows. Mind the stairs, John. They’re slippery.”

Before they could step through the doorway, a dark-haired young man with a face the color of bread dough came running down the hall toward them, stepping at a dangerous speed in and out among the haphazardly arranged patients blocking his course. He came to an awkward, stumbling halt.

“Are you one of the new volunteers come to help us?” The young man waved frantically at nothing in particular and thrust his pasty face as close to John’s as he could contrive, considering he was a head shorter. His hot breath smelled of wine. It was obvious he had over-indulged. John drew back slightly.

“Take care, Farvus!” Gaius said. “This man isn’t here to help you burst pustules. This is John, Lord Chamberlain to Justinian.”

“John! Of course! The friend you’ve spoken about. The one the gossips call John the Eunuch.” The young man leaned toward John again. “Well, John, at least you don’t have to worry about bringing children into this terrible world.”

“You’re impertinent! As a matter of fact, the Lord Chamberlain has a daughter. Go about your business immediately,” Gaius barked at the young man, before turning toward John.

“Now you’re examining me,” John observed.

“Do you mind if I don’t discipline the fellow? We need all the help we can get. Death tends to make people forget who holds authority or the proper manner in which to address them. I’ve even seen aristocrats begging slaves for a last cup of water.”

John shrugged. “Shall we attend to our own business?”

They descended the steep, stone stairway into a cool atmosphere redolent of corruption underlain by a rich, unmentionable sweetness. John would have choked, had the smell of death not become so familiar in the past weeks. Resinous torch smoke massed beneath the vaulted roof.

“You could preserve fish down here with all this smoke,” Gaius remarked. “It does mask the smell a little. They say Hippocrates drove the plague out of Athens with fire. Perhaps what we need is a riot. If the Blues and Greens put the torch to the city again, it might do some good for a change.”

John did not reply, but glanced at the large club leaning against the wall at the foot of the stairway.

“Rats,” Gaius explained.

His companion looked around the dimly lit vault. The dead, laid out in tidy rows between the columns holding up the roof of the disused cistern, were as silent as they were still.

The air, however, was murmurous.

John thought of the spring meadows alive with bees behind Plato’s Academy, where he had studied as a young man. It reminded him of the ancient belief equating bees with souls. However, in the cistern of the dead it would not be bees which buzzed, John reminded himself as he slapped at a fly that hit his cheek like a fat raindrop. Perhaps flies were more likely vessels for souls than bees. They seemed to emerge from death as if from thin air.

Gaius led the way through flickering shadows. The recumbent forms they passed might have been statues, their eyes as blank as those of the marble philosophers and mythological figures decorating the city’s public baths.

“These patients all died from the plague,” Gaius noted. “However, there are still a few ingenious souls in Constantinople who manage to find other ways to depart. We’ve placed them together at the back in case the City Prefect’s men show any interest. Which they haven’t so far.”

An archway, low enough to force John to bend his head, opened into a small chamber housing perhaps a score of bodies.

Gaius scanned them as if he were a shopkeeper surveying the stock on his shelves. “Here’s someone who drowned. Probably not of interest? And this man died in a fall, although—”

“Never mind. Gaius. I’ve found Gregory.”

John gazed down at an aged man with a sharp, beaked nose. Not hawk-like. More like a fallen sparrow, dusty, gray, and still. “How did he die?”

Gaius lumbered over to John’s side. “Ah yes. This one was, in fact, murdered. A knife blade expertly inserted between the ribs and straight into the heart. I couldn’t have done it more accurately. It was an easier death than the plague.”

“Do you recall where he was found?”

“Not exactly. It was in one of those streets running off the Mese, I believe. I’ll look it up in the records. But this isn’t the man you’re seeking, John. And just as well, if you ask me, because otherwise we would have to start believing in supernatural visitations.”

“It’s definitely Gregory.”

Gaius shook his head. “From what you told me, that can’t be. Let me show you something.”

A long wooden table against the far wall held a number of baskets. Gaius rummaged in one and then another.

“It’s astonishing,” he remarked as he searched. “The dead are piling up so fast in the streets thieves don’t have time to rob them all. I’ve been storing such items as came in with or on the departed although no one’s claimed anything yet. There are even a couple of full coin pouches, if you can believe such a thing. Ah, here it is.”

He flourished the scroll he had retrieved from the last basket investigated.

“I’m absolutely certain that is the man I saw come to my door to visit Peter from time to time,” John said.

“Impossible.” Gaius handed the scroll to John. It bore an official seal. “This was found on the murdered man. Your impression is that Peter’s friend has endured hard times, but that can’t be said of this fellow, judging from the documents he carried. Strangely enough, though, his name is also Gregory. However, I can guarantee he certainly wasn’t the sort to make a habit of visiting servants, old friends or not, let alone taking charitable gifts of food from them. This particular Gregory was a high-ranking customs official and therefore a man of considerable means.”