Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires (85 page)

Authors: Selwyn Raab

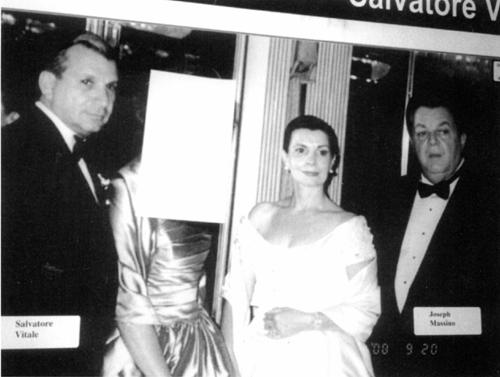

Joe Massino with his wife, Josephine, were in formal dress for the 1999 wedding of one of Sal Vitale’s sons. Vitale’s wife’s face is blocked out because she is in the Witness Protection Program. (

Department of Justice Exhibit

)

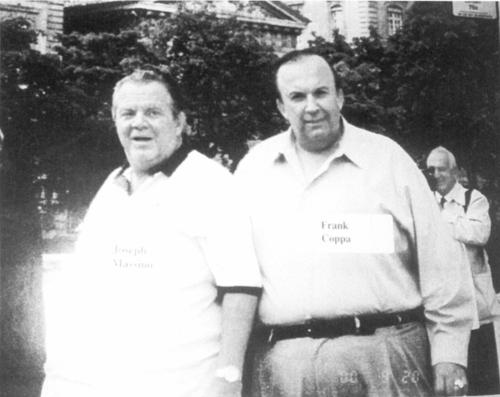

Corpulent capo Frank Coppa picked up the tabs for Joe Massino and his wife on jaunts to France and Monte Carlo in 2000. Massino used overseas trips with capos to mull over family business out of range of FBI bugs and cameras. (

Department of Justice Exhibit

)

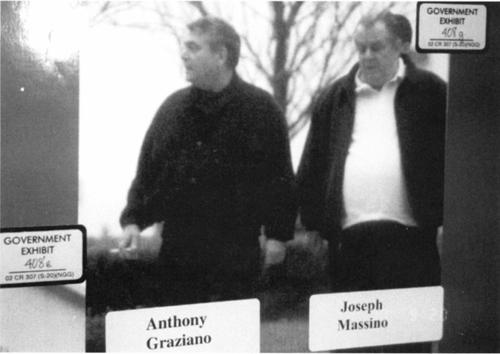

Joe Massino spotted leaving his doctor’s office in Staten Island with Anthony “T. G.” Graziano, a member of Massino’s crime cabinet. The FBI suspected that Massino used the doctor’s office in 2001 as a safe rendezvous for mob chitchats. (

FBI Surveillance Photo

)

After Joe Massino’s arrest, relatives tied a yellow ribbon to a tree in front of his Howard Beach home, signifying that he was a heroic hostage and prisoner of war. Guarding against enemies and law-enforcement snoops, Massino installed closed-circuit cameras in his home that enabled him to spot anyone surveilling the house and street. (

Photo courtesy of Manny Suarez

)

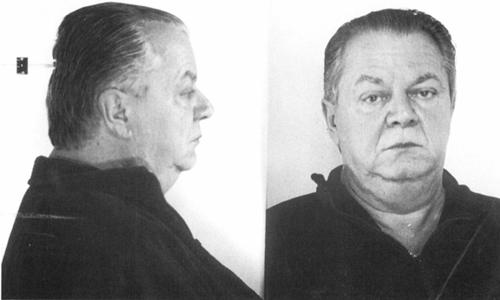

Dressed in a black velour jogging suit, Massino was prepared for arrest on RICO and murder charges when FBI agents came calling at dawn on January 9, 2003. (

Photos courtesy of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

)

The combination of Gotti’s hubris and his complimentary media treatment only intensified the determination of frustrated agents and prosecutors to vanquish him. On bugs he was heard fulminating at the government’s “vendetta” to convict him, and how “tough” the law would be on him if he were ensnared. Yet he repeatedly committed the fundamental mistakes that earlier had gotten him into difficulties, until they proved to be fatal. Aware of the government’s wiretapping and bugging capabilities, he threatened to kill any underling trapped by electronic eavesdropping, including his longtime comrade Angelo Ruggiero. But Gotti disregarded his own directives. Figuring correctly that the Bergin Hunt and Fish Club would be a logical target, he evaded being caught by a bug inside the Bergin’s main room. For Mafia business discussions, he retreated to an adjacent unmarked office, which he was confident was unknown to investigators and safe from electronic ears. Soon after becoming boss, he was enraged to learn that the state Organized Crime Task Force had planted mikes in his private den. Evidence from his office conversations was used to convict other Gambino mobsters, and taped conversations were the underlying element in his trial for the shooting of carpenters’ union leader John O’Connor.

Yet three years after the Bergin bug fiasco, he repeated the same blunder at the Ravenite Club in Little Italy. Rather than being inconvenienced by walk-talks in cold weather or rotating his meeting places, he felt comfortable in the hallway at the rear of the Ravenite and upstairs in the homey Cirelli apartment. It apparently never dawned on him that informers would reveal his secret havens in the Ravenite building, just as they had his private office at the Bergin Club. Again, he was too lazy or overconfident to dodge investigators by alternating meeting places or sweeping them for bugs. His inability to hold his tongue continued in prison. At Marion, he made incriminating statements about his son, despite knowing his words were being recorded and could be damaging to his own flesh and blood.

Gotti’s indifference to surveillance created extraordinary difficulties for himself and all of his capos. He continually ignored the basic principle that the Mafia presumably was a secret organization. The entire family knew that the FBI and detectives often videotaped and photographed everyone in the vicinity of the Ravenite. But Gotti disregarded the danger, demanding obsequious attendance and reports to him there by the hierarchy and capos. His decree delighted FBI agents at their observation post in an apartment two blocks from the club. Their pictorial records became part of the evidence

against Gotti at his final RICO trial. Additionally, the compulsory gatherings at the Ravenite allowed the bureau to identify previously unknown Gambino members. Videotapes and still photographs of capos and soldiers showing up at the Ravenite were used as valuable circumstantial evidence against them at RICO enterprise trials.

His inability to judge loyalty and talent were pitfalls for Gotti. Following the murder of his original underboss, Frank DeCicco, Gotti depended heavily on Sammy the Bull Gravano, first as his consigliere and then as underboss. Gravano was an efficient choreographer for murders Gotti wanted, and a big earner who delivered more than $1 million a year to the boss. But his record for sacrificing others should have been a cautionary signal to Gotti. Previously, whenever Gravano became entangled in an internal dispute, his solution was to kill the rival and shift blame for the mishap onto someone else. Even among unprincipled mobsters, he had a reputation for unscrupulousness. If advancement required whacking his brother-in-law or a business partner, Sammy the Bull went along with it. Because Gravano, unlike many skilled mafiosi, had never been imprisoned, Gotti had no idea of how he would react in the crucible of prison. He misjudged Gravano’s dedication to him and the myth of Cosa Nostra loyalty. According to Bruce Cutler, Gravano misrepresented himself to FBI agents and prosecutors as a strong-willed, tough-as-nails gangster who had confronted Gotti when he had disagreed with his Mob policies. The lawyer recalled that in Gotti’s presence, “Gravano was always subservient, even obsequious around John.”

And when the climactic test came, Sammy’s self-preservation was more important to him than saving his boss and dozens of his crime colleagues.

Double-crossed by Gravano, Gotti next placed his faith in blood ties by designating his son as his surrogate and successor. Doing so, he disregarded Junior’s inexperience and the resentment engendered in the family by this conspicuous nepotism. Mafia gangs traditionally had counted on merit, not the boss’s kin, for picking competent leaders; sons were not granted the right of automatic succession and guaranteed wealth in the Cosa Nostra. Gotti knew from contemporary events in the Colombo family the danger of manufacturing a dynasty. Carmine Persico’s promotion of his son without approval from a majority of capos had ignited a destructive civil war among Colombo factions. The Gottis averted a similar rebellion, but Junior’s incompetent tenure culminated in his own conviction, and prison sentences for more than a dozen other capos, soldiers, and associates.

With his son imprisoned in 1999, Gotti’s last hope for clinging to power and maintaining a dynasty was through brother Peter. As a close relative Peter, like John Jr., could visit him in prison and transmit news and receive advice in their private code. Long overshadowed by his more ambitious kid brothers, John and Gene, Peter had served them as a compliant assistant, a glorified gofer. John had appointed Peter capo of the Bergin crew, and after Junior’s jailing, bestowed upon him the mantle of acting boss. Before matriculating as a full-time mobster, Peter had worked ten years for the New York Sanitation Department, and obtained a disability pension of about $2,000 a month for an on-the-job injury after falling off a garbage truck. The FBI’s Gambino Squad had a low regard for Peter’s underworld abilities. “He’s not exactly a Rhodes scholar nor particularly aggressive,” Mouw observed when it was learned that Peter was the new acting boss. “Does he have the capabilities of running a Mafia family? Absolutely not.”

Trying to avoid the limelight that had been ruinous for his brother, Peter stayed close to his sanctuary in Queens, the Bergin Club. Like the rest of the Gambino family, the club had fallen on hard times; half its space was taken over by a butcher shop and a delicatessen. The new don’s brief fling with glory evaporated a week before his brother died in prison. Arrested on a RICO indictment in June 2002, Peter was cited as being the acting Gambino boss and the head of the family. A year later, sixty-two-year-old Peter Gotti was convicted for the first time in his life, found guilty of extortion, money laundering, and corrupt control of a longshoremen’s local.