Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires (55 page)

Authors: Selwyn Raab

In the mid-1980’s, the excise and sales taxes amounted to about 30 cents on a gallon, a sizable revenue for federal, state, and local governments. The Russians devised a subterfuge to siphon the taxes from the pumps to themselves by setting up dummy or front wholesalers. They formed what became known as “daisy chains” of companies that supposedly transferred gasoline supplies to one another. There would be a sequence of paper transactions among five or six companies although no exchanges actually occurred. To escape detection when state or federal agents came looking for the overdue taxes, the Russians used resident or illegal aliens like Misha as fronts for scores of fictitious empty-shell companies that existed only on corporate papers. A dummy or “burn” company always was listed on the transfer records as the one making the final sale to retail stations and collecting the taxes. That company never existed; it was used just to bewilder the tax collectors when, months later, they noticed gaps in both the excise and sales revenues. The Russians actually delivered the gasoline and kept or stole the taxes paid by the retailers. The “front” immigrants were ignorant of the magnitude of the deals that had gone down and, like the unwitting Misha, usually were out of the country when finally traced by investigators.

It was a racket that became widely known as “gasoline bootlegging.” The tax cheats who invented it were Jewish “Russian Mafia,” immigrants from the Soviet Union who established a beachhead in New York, mainly in the Brighton Beach section of Brooklyn. The Russians were creative but they were no match

for the original Mafia, especially the Colombo capo Michael Franzese, then in his early thirties. He had been efficiently indoctrinated in unrestrained law-breaking by his father, John “Sonny” Franzese, a former Colombo underboss.

In 1980 three Russian gangsters, Michael Markowitz, David Bogatin, and Lev Persits, solicited Michael Franzese’s help in collecting a $70,000 debt stemming from one of their gasoline-tax swindles. Amazed at the largesse flowing from the gasoline pumps, and armed with the muscle power of his troops, Franzese gradually moved in on the Russians. His enforcers could guarantee the expeditious collecting of debts from gasoline stations. And through connections with state officials, the Colombos obtained licenses needed by the phony fuel dealers to pull off the “daisy chain” tax thefts.

Ever generous, Franzese allowed the Russians to continue their operations, handling all the paper work and taking most of the risks as long as they paid “tribute” to him. The Colombo end was 75 percent of the profits and the Russians’, 25 percent. Franzese worked out a similar deal with a larcenous non-Russian wholesaler, Lawrence Iorizzo, who had also discovered the tax larceny loophole.

“To give you an idea how lucrative the gas tax business was, it was not unusual for me to receive $9 million in cash per week in paper bags from the Russians and Iorizzo,” Franzese later confessed. At one point, the Colombos and their partners were stealing as much as 30 cents a gallon from the sale of about 500 million gallons a month, according to Franzese’s figures. At their peak, the thefts generated $15 million monthly for Franzese and his Colombo partners.

By the mid-1980s, at the time of the Commission trial, the Gambino, Genovese, and Lucchese families wanted a share of the gasoline gusher. Following the lead of the Colombos, the other borgatas forged similar alliances with Russian hoodlums in the booming bootleg business in the city, Long Island, and New Jersey. Each family nominated a wiseguy as a “point man” to check the books and harvest payoffs of at least four or five cents on each gallon sold by the Russians. Investigators later estimated that in the 1980s and early 1990s, the Mob and their Russian collaborators fleeced the government of $80 million to $100 million a year in excise and sales taxes.

The immensely profitable gasoline-tax racket was a new Mafia venture, but the five families never relinquished their hold on the New York construction industry, their old sinecure. Seven years after the Commission trial ended, the saga of the West Side Highway unfolded to demonstrate how Mob families continued blending their talents to profit from their grip on the industry. The highway

plot involved the cooperation of three families, each trading favors and pulling strings with contractors and unions. It was another chapter in how mafiosi-inspired corruption inflated overall building costs in the city by at least 10 percent on each project.

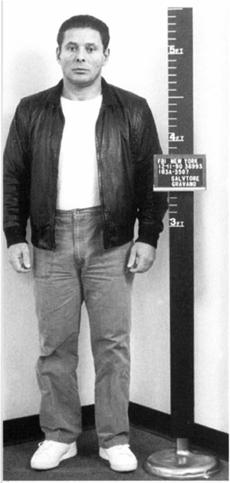

A construction contractor who led a double life as a Mafia capo, the silver-haired Thomas Petrizzo was secretly photographed at a wake for a Colombo family member. One of Petrizzo’s mob coups was pilfering a small fortune in steel when the West Side Highway in Manhattan was demolished.

(FBI Surveillance Photo)

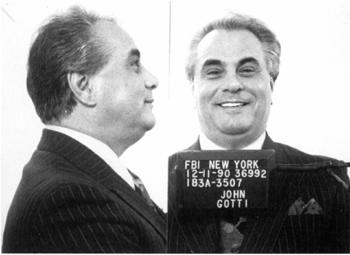

While a mob war raged in New York, Carmine Persico (far left) tried to influence events from a federal prison in Lompoc, California. Serving combined sentences of 139 years, “the Snake” was permitted by prison authorities to organize an Italian cultural club where he and inmate buddies could meet to reminisce about old times.

(Author’s archive)

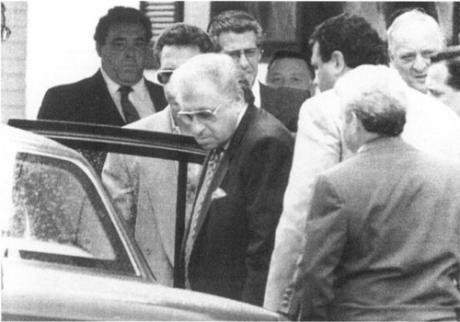

The new boss of the Gambino family, John J. Gotti, (right), wearing an Oakland Raiders jacket on a walk-talk in 1986 with Anthony “Tony Lee” Guerrieri, a soldier, in front of the Bergin Hunt and Fish Club, Gotti’s headquarters in Queens. Investigators overhead Gotti in a bugged conversation at the Bergin boast about creating an indestructible Mafia borgata.

(FBI Surveillance Photo)

Frank DeCicco, a Gambino capo, who was instrumental in setting up the hit on Paul Castellano, was Gotti’s first underboss. He was killed in a car explosion that failed to get Gotti, the main target, in revenge for Castellano’s murder.

(Photo courtesy of the New York City Police Department)

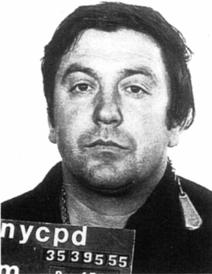

Bosko Radonjich, a gangster and Gambino ally, allegedly helped funnel a $60,000 bribe to a juror to fix Gotti’s first RICO trial in 1986. Gotti’s acquittal bolstered his reputation for invincibility.

(Photo courtesy of the New York City Police Department)

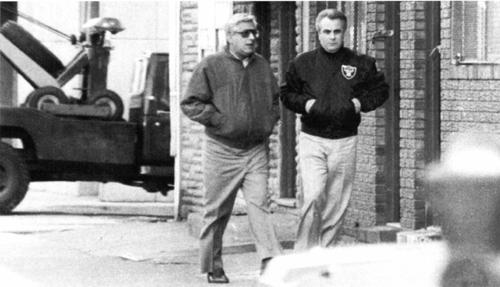

Gene Gotti (left), John’s younger brother, was convicted on narcotics trafficking charges, largely on evidence the FBI obtained by bugging the home of Angelo “Fat Ange” Ruggiero (center). John Carneglia (right), a Gambino soldier and enforcer, was handpicked by Gotti for the assassination squad that ambushed Paul Castellano.

(Photos courtesy of the Federal Bureau of Investigation)