Final Analysis (38 page)

Authors: Catherine Crier

A

s this book goes to press, Susan awaits her sentencing by Judge Brady. Having found an attorney, Linda Fullerton, currently willing to handle her appeal, she received a six-month extension in August to obtain a transcript and file necessary motions for a new trial. While Susan’s decision to represent herself was a disastrous misstep, it is unlikely that the trial judge will determine that this obvious “ineffective assistance of counsel” will compel a retrial. The old adage, that anyone with himself as a lawyer has a fool for a client, may be true, but this poor decision is not legal grounds for a new trial. Despite the unorthodox proceedings, there does not appear to be any glaring errors that will ensure Susan receive another shot at an acquittal.

Susan has already been behind bars for several years. Interestingly, she seems to have adapted well to her regimented environment. Despite her assertions that Felix was an oppressive, controlling spouse, it may be that years of this relationship prepared her for her time in prison. She spends her time reading and writing, often isolating herself from the other inmates. Ironically, now she has plenty of time for the contemplative life she imagined leading in the wilds of Montana.

As tragic as her circumstances may be, they do not compare with the burdens her three sons may carry throughout their lives. The long-term psychological effects of their upbringing will manifest in myriad ways in the coming years. Ironically, eldest son Adam told me that he is contemplating a career in law. He should be able to get into a good program,

having excellent grades as an English major and many accolades as one time student body president and head of the university’s honor society. He held down a job while achieving all of this and, at least outwardly, seems to be creating a semblance of normalcy in his world. Professing love for his mother, he nevertheless refuses to get sucked into an ongoing family drama now that the trial has concluded. However, he is the “father figure” now, and his two younger brothers will need his guidance.

The youngest son, Gabriel, was very lucky to have the Briners enter his life. A well-adjusted couple with big hearts, this duo is determined to help Gabe survive the trauma of his childhood. Their guidance and support will be critical, as he must have a healthy blueprint for families and relationships to heal these scars. As with the other boys, he is bright and capable, and with serious work, he may succeed in processing the emotional violence of his youth.

The one most in danger, I believe, is the middle child, Eli. Throughout the trial, he seemed to have adopted his mother’s delusions of conspiracy and her rebellious actions against anything that smacked of authority. He willingly chronicled a history to conform to her world despite so much evidence pointing to another reality. His own choices since Susan’s incarceration have been consistently bad; from his relationship with the much older girlfriend that produced repeated charges of abuse, to his acting out in ways that virtually assured that authorities, especially the police, would have to step in and control his behavior. This vicious circle—paranoid beliefs about authority, acting out so that he becomes a target and the inevitable clamping down on his freedom—will not be broken unless Eli gains personal insight that, thus far, does not seem to exist.

After many years at the hands of two people well-educated in psychology, it is ironic that more counseling and therapy may be the only hope for Eli’s salvation. Some people are capable of working through emotional troubles on their own or at least compartmentalizing the past such that they appear to function well in their daily lives. I am not optimistic this will occur for Eli. Despite his physical appearance, time spent around this young man made me acutely aware of his frailties. Coupled with the detrimental impact his recent imprisonment has had, and the

essentially life-time incarceration of his only living parent, I do not believe the prognosis for Eli’s future is a good one.

At present, Eli has been released from jail. His grandmother, Helen, a figure virtually unknown to him until Susan’s arrest and one who reinforces her daughter’s skewed world view, has a condominium waiting for him in San Diego, but Susan is objecting to this arrangement. She wants him to stay in the Miner Road house completely alone, despite the planned sale of that home. Sadly, Eli continues to listen to such irrational advice from his mother.

He dreamed of entering the military. Maybe the discipline would have been a good balance for him, but I believe that insubordination would have been his likely reaction to that environment. Nevertheless, his criminal record has now foreclosed this career path. Will he reconcile with Adam and Gabe such that his remaining family can form a support unit? Again, that does not seem likely in the immediate future. Can Eli manage any remaining monies from his parent’s estate as he tries to get his feet on the ground? I fervently hope that alternatives present themselves for this troubled young man, but I cannot conjure such a scenario at present. I worry that, without extraordinary intervention, the Polk story has more tragedy in store for him.

In stories such as this, I am always searching for the larger meaning. Obviously, the issue here is recognizing the enormous repercussions that flow from dysfunctional families. Both Susan and Felix were set on a path in their early years that propelled them toward pain and grief in their lives. That the two would find each other is not so unusual. Society has learned much about codependent relationships in recent decades. Yet there were many warning signals ignored along the way. Many people in positions of responsibility were aware of the improper, unethical beginnings for the Polks, yet did nothing to address this.

Even more evident were the rampant behavioral problems exhibited by the Polk sons at relatively early ages. School professionals, members of law enforcement, jurists, and psychologists—all could see that these boys were having grave troubles, but they did little to challenge the underlying conditions at home. With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to criticize,

but the incidents were too numerous to chalk them up to minor difficulties in an otherwise normal family.

The literature on dysfunctional families has grown astronomically in recent years. The requirements that officials at school and elsewhere report and react to such events exist for a reason. More aggressive behavior by these authorities had no assurance of success, but much more could have been done.

Ultimately, the Polk family seemed to be on a runaway train barreling toward a cliff with no way to halt the looming tragedy. If Susan had not killed Felix, I believe another catastrophe would have presented itself. I cannot fathom that a divorce between these two people would have ended their dangerous dance; nor would a legal dissolution have repaired the younger boys, Eli and Gabriel. Adam simply removed himself from the family unit, exhibiting enough inner strength to reject the poison that was still infecting his siblings. What might have occurred had the younger boys continued as players in their parent’s drama will never be known. But it is not hard to imagine that some sort of violence would have occurred—an outcome that still threatens Eli.

Our families are the most formative influence on the human psyche. For better or worse, a childhood forever shapes attitudes, outlooks, and more subtle perceptions about the world. Felix brought enormous trauma and inner turmoil to his relationship with a very troubled young woman and, instead of healing her wounds, exacerbated her serious psychological problems. The couple then projected their disastrous mix onto three helpless children.

This is the story of so many of the people who fill our prisons today. Whether rich or poor, smart or simple, this group usually has been damaged long before they act out. Society cannot simply empathize and open prison doors because of a bad childhood, but it should understand that without addressing this insidious damage, incarceration will do little to affect what makes such people dangerous to others or themselves. Prison therapy is often seen as a weak, “liberal” response to criminal behavior, but it is one of the few measures that might actually rehabilitate those who will one day walk our streets again.

As you read this, adults and children all over the country are being subjected to mental and physical violence in a place that should be the most safe—their homes. Their personal traumas regularly become bigger problems for our schools, our workplaces, and the criminal justice system. We must better address this reality to save not only these tragic souls, but our larger family—the human race.

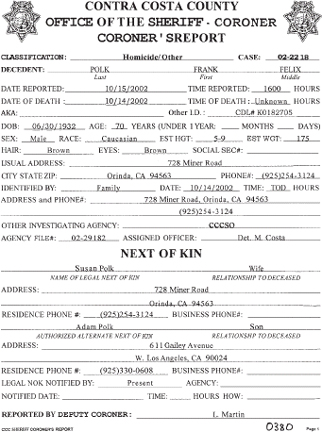

A copy of Felix’s naval records, which Susan used during the trial.

The letter written by naval doctors that details their diagnosis of Felix’s suicide attempt as a schizophrenic reaction

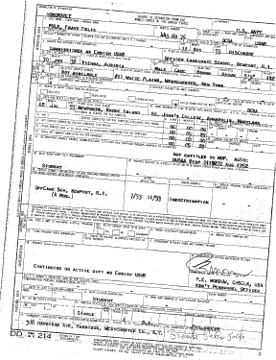

Felix’s 1955 suicide letter

Susan, younger, at one of the Polk’s earlier houses

Susan and Felix on a trip to Europe

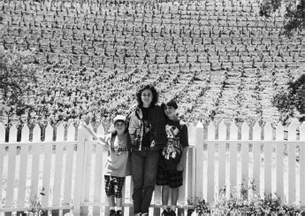

Susan and her children on a trip to a California vineyard

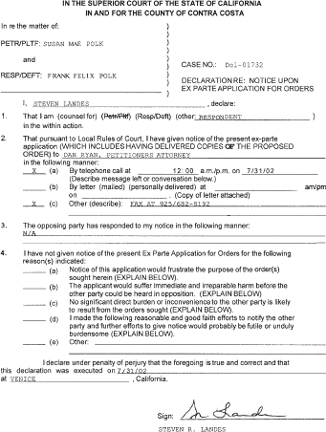

A page from the legal case of

Polk v. Polk

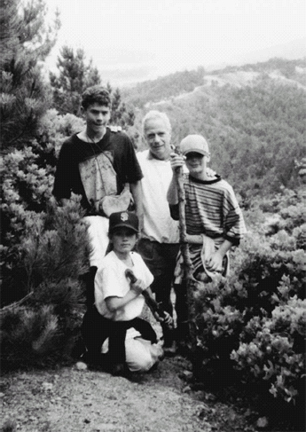

Always an avid outdoorsman, Felix loved hiking with his boys.

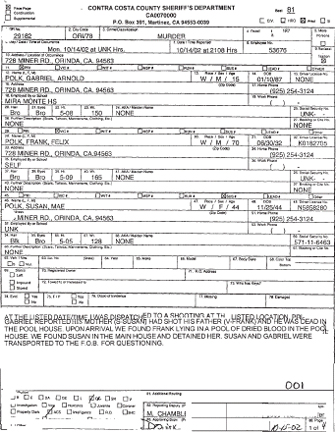

The police report from Felix’s death scene

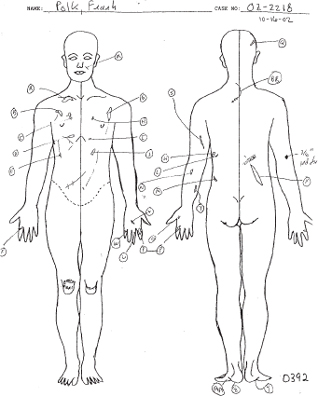

Dr. Peterson’s wound chart from Felix’s autopsy. This diagrams each of the places where Susan’s knife hit Felix.

The knife that Susan claimed she used when she killed her husband

A bloody footprint on the floor of the Miner Road pool house taken by Costa County Police Department. The footprints would prove a subject of great controversy during the trial as Susan used them to demonstrate procedural errors on behalf of the police department.

A police photo of the Polk’s Miner Road estate