Films of Fury: The Kung Fu Movie Book (15 page)

Read Films of Fury: The Kung Fu Movie Book Online

Authors: Ric Meyers

But the one man who may have made it all possible pretty much disappeared into that good night. That would be the magnificent I Kuang

. Born in Shanghai in 1935, Kuang moved to Hong Kong in the 1960s to pursue a successful career as a science fiction and martial arts novelist. Although several of his books were adapted to movies, his first original screenplay was for

The One

-Armed Swordsman

, and he rapidly replaced Chang Cheh

as the Shaw Studio’s top scripter. In addition, his independent contract allowed him to work for other studios and directors — an opportunity he took ample advantage of. Not only did he write the bulk of Chang Cheh’s best films, but also those of Liu Chia-liang

, and even Bruce Lee

. At last count, Kuang has supplied well over five hundred scripts to studios throughout China, and that isn’t even including the many screenplays he produced under pseudonyms.

As of this writing, Sir Run Run Shaw

, and the Studio he helped create, still lives. Celebrated as a philanthropist, he has donated literally billions of dollars to charities, hospitals, and schools. At the age of one hundred and three, he remains married to Mona Fong

, who had been both his mistress and producer of all the Studio’s movies.

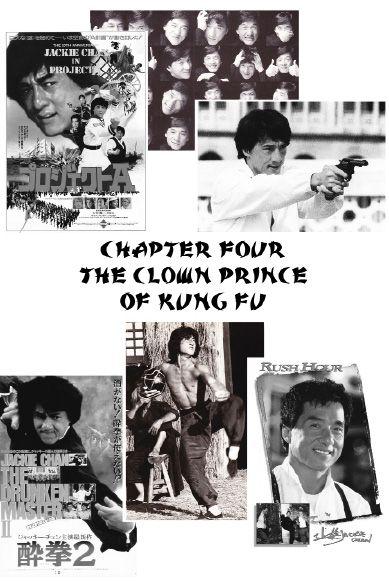

Picture identifications (clockwise from upper left):

Project A

; the many faces of Jackie Chan

; Jackie Chan

in

Police Story

3: Supercop

;

Rush Hour

; Jackie Chan

and Simon Yuen

in

Drunken Monkey

in a Tiger’s Eye

;

Drunken Master 2

.

Jackie Chan

was born in 1954 with the name Chan Kong-sang (aka Chen Gang-sheng) to a chef father and a maid mother. His parents were poor but steady workers. Until he was seven, his folks cooked and cleaned at the French embassy in Hong Kong. But no matter how hard his father toiled to teach him humility and virtue, Chen/Chan followed in Bruce Lee

’s footsteps: finding street fights.

Then came the single most meaningful moment in his life: his parents secured jobs at the American Embassy in Australia. Only two problems: they decided not to bring their young son and to enroll him in the China Drama Academy. This benign-sounding institution was an old-style Peking Opera

school where, for the next ten years, Kong-sang would eat (not much), sleep (not much), and slave (loads) to learn acrobatics, song, dance, acting, and kung fu under strict, martial discipline.

His headmaster, Yu Zhan-yuan

, was half-respected and half-feared. He was a stern taskmaster who was quick to punish and slow to compliment. But at least he was teaching them something useful in the world of Hong Kong show business. That, unfortunately, didn’t include reading or writing. While others in the school sought to survive, stay under the radar, or curry the master’s favor, Chan dedicated himself to impress.

He soon manifested the personality that shaped his life: that of the textbook abandoned child. Since, subconsciously, he couldn’t help feeling that his parents might not actually love him, he set out to make everyone else do it instead. Eventually he gained the nickname “Double Boy,” since he tried doubly hard than any one else. That held him in good stead when he finally “graduated” the Academy, only to find no call for Peking Opera

performers.

But he had already been featured in movies as a child actor —

Seven Little Valiant Fighters: Big and Little Wong Tin Bar

(1962) and

The Eighteen Darts

(1966) being two of the better known. In 1971, at the age of seventeen, Chan found it the perfect time to use his burgeoning skills. His Academy big brother Sammo Hung

Kam-po (aka Hung Chin-pao) was already established as one of the most sought-after action directors, so Chan soon found himself in

The Little Tiger of Canton

(aka

Snake Fist Fighter

aka

Master with Cracked Fingers

, 1971), but, truth be told, he didn’t make much of a favorable impression — not with his narrow eyes and greasy little mustache.

He fared much better as an anonymous stuntman — doubling the villain in

Fist of Fury

or getting his neck broken by Bruce Lee

in

Enter the Dragon

. “Everybody idolized Bruce,” Chan told me years later. “So no one would talk to him. But I asked him if he wanted to go bowling with us after shooting wrapped for the day. He just looked me up and down, and walked away. But then, that night, in he comes and sits down next to me at the lane where we’re bowling. He just sits there, watches us bowl for ten frames, then thanks me and goes. It was like the whole place was holding its breath! As soon as he leaves, everybody started slapping me on the back and shaking my hand. He really gave me face that day.”

But even Bruce’s kindness and Sammo’s help wasn’t enough to keep the young man gainfully employed, so he joined his parents in Australia, but only found work in construction. Its only benefit was gaining him muscles, and an American nickname. A fellow worker named Jack had trouble pronouncing Kong-sang, so he started calling Chan “Little Jack.” Then, when the other workers had trouble pronouncing “Little Jack,” they shortened it to “Jacky.”

Meanwhile, back in Hong Kong, a hopeful Malaysian film producer named Willie Chan

Chi-keung was looking for a way to establish himself. He was duly impressed by Jacky’s contributions to such Sammo-influenced films as

Hand of Death

(1975, directed by a promising newcomer named John Woo

), and sold the flagging Lo Wei

on the idea that this fledgling star was the perfect choice to become the “new Bruce Lee

.” Jacky, bored by construction work and unable to find contentment down under, was ready to give kung fu films another try. Intrigued by Chan’s possibilities, Wei signed Chan to a long-term contract, changed his name to Sheng Lung (“Little Dragon

”), and set him immediately to work on

New Fist of Fury

(1976).

This film takes up where Bruce Lee

’s left off, with the survivors of the kung fu school escaping Japanese soldiers to come across the Chan character. Nora Miao

, who was the female lead in the Lee picture, returns to her role, and teaches Jacky what is essentially their idea of jeet kune do

— here called Ching Wu. Then he goes back and takes vengeance on Lee’s murderer in a rote, lackluster way.

Although hardly inspired, his performance seemed to fit Lo Wei

’s bill, so he plunged Chan into eight more movies over the next two years. But this was 1976 — the year Liu Chia-liang

made

Challenge

of the Masters

, Chang Cheh

made three Shaolin movies starring Fu Sheng

and Ti Lung

, and a young upstart, independent producer named Ng Sze-yuen

made a surprise hit called

The Secret Rivals

. What Lo Wei was grinding out made money, sure, but otherwise just wasn’t cutting it.

Nor was

Shaolin Wooden Man,

Jacky’s second 1976 film for Wei’s company (directed by Chen Chi-hwa

). It was another wooden (all puns intended) kung fu film — with Chan taking revenge for his father’s death thanks to the coaching of a handy Shaolin monk. But this was the first film in which Jacky was given a little freedom in the fight scenes. Slowly, he started to find his way. There was little chance to improve in

Killer

Meteor

(1977) since Jacky was playing the villain and Jimmy Wang Yu

was playing the stolid, limited hero. At least in

Snake-Crane Art of Shaolin

(1977) — a Chang Cheh

knock-off also produced by Wei and directed by Hwa — Jacky was back as the protagonist. He was becoming more proficient, while displaying more charisma.

To Kill With Intrigue

was next on the treadmill. Lo Wei

’s company didn’t have the money, materials, or even inclination to make great kung fu films. Instead, they relied on Double Boy’s eagerness to please. But even a performer of Chan’s ability couldn’t do enough with terrible working conditions, mediocre scripts, or his producer’s desire to maintain his ego’s status quo. When this film failed at the box office, Wei all but gave up on Chan … which turned out to be the actor’s trump card.

Contractually stuck with Jacky, Wei basically gave him carte blanche on his next picture. Chan took the opportunity to, in his words, “fool around.” Seeing that everyone was trying to copy Bruce Lee

, he decided to do the opposite. Since Bruce kicked high, Jacky would kick low. Since Bruce was serious at all times, Jacky decided to make faces. Since Bruce never got hurt or made a mistake, well, you know…. Instead of fighting against the inevitable restraints of bad martial arts filmmaking, Chan went with them.

Half a Loaf of Kung Fu

(1978) was the first recognizable “Jacky Chan Film.” He both had fun with, and made fun of, kung fu film clichés. In the opening credits alone, he lampooned exaggerated sound effects, frenetic editing, wooden men, the famed Japanese film series about Zatoichi the Blind Swordsman

, and even

Jesus Christ Superstar

. His inventive, unusual work fell on blind Lo Wei

eyes, so it was back to the grindstone for three more uninspired efforts: the 3D

Magnificent Bodyguard

(1978), the Liu Chia-liang

Spiritual Boxer

knock-off

Spiritual Kung Fu

(1978), and

Dirty Ho

knock-off

Dragon

Fist

(1978) — all of which Jacky got to contribute his fight choreography to, since Lo Wei didn’t seem to care. He had apparently resigned himself to doing the best he could with the rest of this “box office poison’s” contract.

But two other people really seemed to care. There was the aforementioned Ng Sze-yuen

— once assistant director of Jimmy Wang Yu

’s

The Chinese Boxer

, and now the creator of the first major independent movie company, Seasonal Films. Ng had been intrigued with

Half a Loaf of Kung Fu

, and saw the glimmer of a market that the two major kung fu film studios, Shaw Brothers

and Golden Harvest

, weren’t really serving.

Then there was Yuen Wo-ping

. The son of venerated Simon Yuen

Hsiao-tien, a master of stagecraft and northern-style kung fu who personally trained all seven of his children, Wo-ping had seen his father play kung fu villains alongside Shih Kien

in the

Kwan Tak-hing Huang Fei-hong series, as well as kung fu masters in Chang Cheh

’s

Shaolin Martial Arts

(1974) and Liu Chia-liang

’s

36

th

Chamber of Shaolin

and

Heroes of the East

. As Ng saw something funny in Jacky Chan, Wo-ping saw something funny in his father.

Lo Wei

, however, didn’t smell anything funny when Ng asked him to loan Jacky Chan to Seasonal for a film or two. All he smelled was money, and traded Jacky over with an ostensible “good riddance.” The three men — Chan as star, Ng as producer, and Wo-ping as director — were on exactly the same wavelength. Inspired by Liu Chia-liang

’s

Spiritual Boxer

, they did it three better with

Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow

(1978), a brilliantly conceived and executed “new wave” kung fu comedy featuring Jacky as a hapless, mischievous, well-meaning bumpkin, Simon Yuen

as an incognito, on-the-run, consummate snake style practitioner, and Huang Jang-li

as a vengeful eagle claw killer determined to wipe out the snake school.

Chan seemed to explode out of the screen with joy at finding his place in the kung fu film firmament, while Wo-ping’s directing skills were never more effective. The audience shared their delight throughout, and only grew in exultation when Chan’s character develops “cat style” kung fu to defeat the eagle master. The film’s success was immediate and almost overwhelming, but the trio were already hard at work on the follow-up.

Drunken Monkey

in a Tiger’s Eye

(aka

Drunken Master

, 1978) proved to the trio, and everyone else, that

Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow

was no fluke. In fact, it was the rare sequel that improved on the original in virtually every way. The first masterstroke was to have Jacky play a new kind of Huang Fei-hong — a young, roguish, teenager who came before the august healer. The second was to have Simon Yuen

play the legendary Beggar Su, a beloved historical character. The third was to immortalize Drunken Style, which Liu Chia-liang

had featured in

Heroes of the East

, but not to this potent effect.

Although essentially a remake of

Eagle’s Shadow, Drunken Master

’s concepts were streamlined, and this new picture stands as one of the sleekest, flat-out, action-filled kung fu comedies. But quantity of action is not enough. Quality of action and character was the object here, and while Chan’s character, nicknamed “Naughty Panther,” moved from one fight to another, the imagination that went into creating the wonderful situations is extraordinary. Although essentially one long action sequence (the outlandish training scenes can be considered part of the action), the movie manages to build until the battle between a tiger claw hired killer and the Naughty Panther.

Half the time Panther is being trained (tortured), while the other half he tries to escape … but is always outwitted by the drunken master who teaches him the “eight drunken fairies” — a style that requires ample portions of alcohol. Chan “graduates” from the training part and moves into the impressive “forms” sequence, before the inevitable and anxiously awaited blow-out finale. There, Panther must save his honorable father from a hired tiger-claw killer (again played by exceptional leg fighter Huang Jang-li

), and does so by inventing a new, delightful, amalgamation of the eight drunken fairies on the spot.