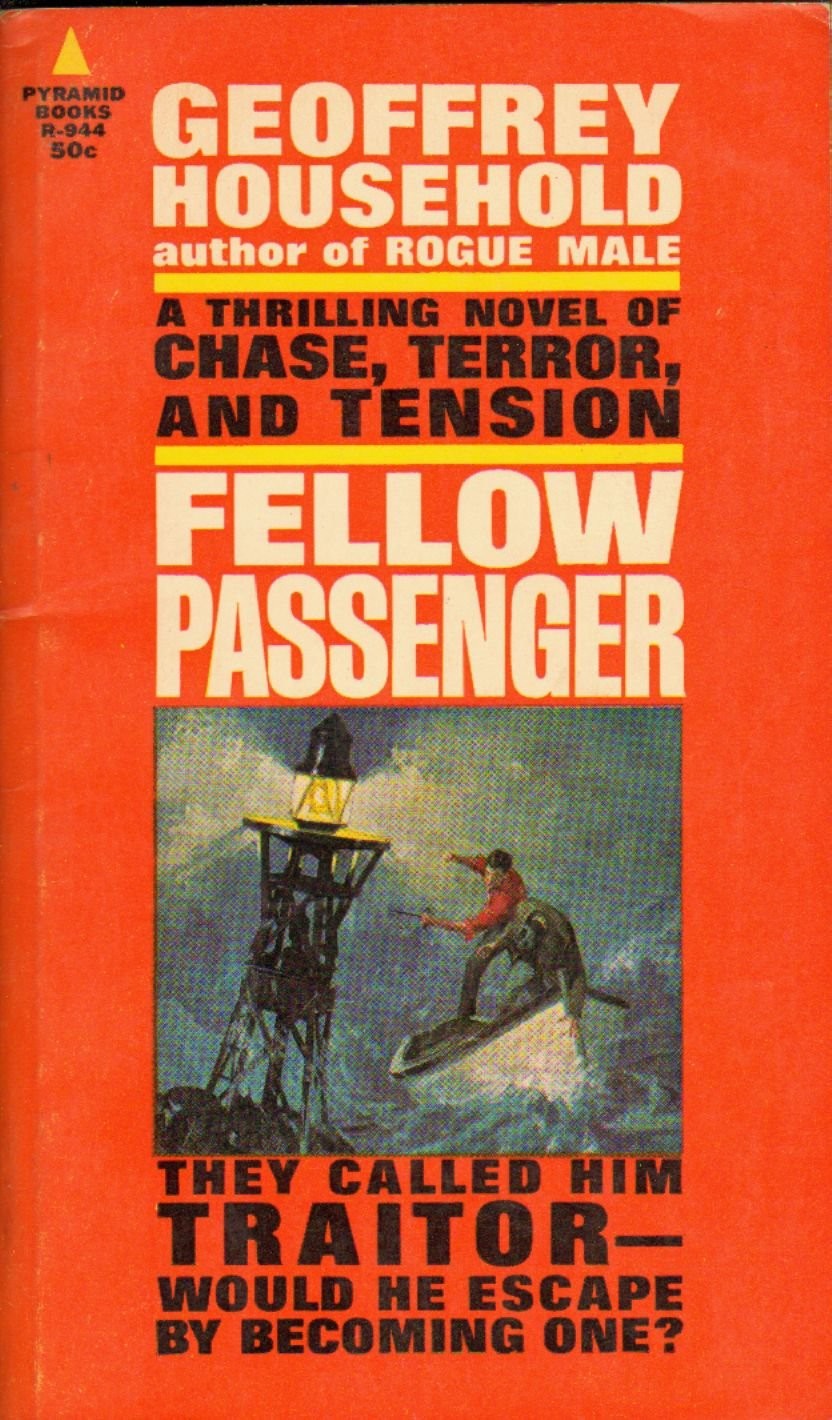

Fellow Passenger

Authors: Geoffrey Household

Tags: #Fiction, #Thrillers, #General, #Suspense

| Fellow Passenger | |

| Geoffrey Household | |

| Hachette UK (1954) | |

| Rating: | ***** |

| Tags: | Fiction, Thrillers, General, Suspense |

| Fictionttt Thrillersttt Generalttt Suspensettt |

An international scoundrel recalls his life of intrigue and adventure in a witty and exciting nonstop thriller

Held prisoner in Britain’s fabled Tower of London, Claudio Howard-Wolferstan revels in his well-earned notoriety and reflects on the events that landed him here. A rogue and an adventurer of English and Ecuadorian descent, he has lived a globe-trotting life of peril and excitement, driven by an addiction to the adrenaline rush that comes with placing himself in constant, life-threatening jeopardy. Having used a youthful flirtation with communism to its greatest advantage, he recalls with pride a satisfying career of break-ins and burglaries, brazen deceptions, wild escapes, and daring exploits that made him a target of the British MI6 intelligence service and Soviets alike, and ultimately landed him in the most fabled lock-up in Great Britain. But in an international atmosphere of mistrust, tension, and warring political philosophies, there will always be a place for his kind, and the world hasn’t yet heard the last of Claudio Howard-Wolferstan.

In the pantheon of great twentieth-century thriller writers, Geoffrey Household, acclaimed for his evocative and colorful locales, deeply human characters, and distinct storytelling voice, occupies a place of honor besides such notable names as Eric Ambler, Ian Fleming, and Len Deighton. Household’s breathtaking tales of adventure and intrigue are as enthralling today as they were then, and

Fellow Passenger

shines with excitement, invention, and wit—a virtuoso performance by a true maestro.

~ * ~

Fellow Passenger

Geoffrey Household

No copyright  2015 by MadMaxAU eBooks

2015 by MadMaxAU eBooks

~ * ~

THERE IS SATISFACTION in being imprisoned in the Tower of London. It seems to set a man, however undeservedly, in the company of the great. I wonder if criminals feel the same about Dartmoor. It is likely. After all, a sentence of twenty years, served in Dartmoor, does mean that one has reached the summit of one’s profession.

I wish I could claim that the blackness of my crime was worthy of the grandeur of my prison, but the fact is that I do not know whether I can be found guilty of High Treason or not; nor does a somewhat embarrassed State. That suits both parties. The Government is in no hurry to decide what shall be done with me. I, so long as they continue to keep me safe from newspaper reporters, am in no hurry to leave. The food, while uninteresting, is at least as good as that of the average English hotel, and the service suggests a club in which the rules are rather too stringent and the staff a little too ceremonious in manners and dress.

There is also the blessing of leisure, as well as a strong tradition for its use. So, for my own amusement, I shall emulate Sir Walter Raleigh and Archbishop Laud. Like me, they were innocent of High Treason but thoroughly deserved the accusation. That, I think, is a combination which lends itself to literature.

I have no intention of justifying myself, for I do not feel in the least ill-used. If I were of pure English birth and shared the national gift for solemn indignation I should probably write to

The Times

- assuming that from this institution one is permitted to address the other - and kindle the sympathies of those excellent citizens who fret themselves about the eccentricities of birds and the injustices of bureaucrats. But I spent my youth in Latin America, and I am too much in love with the world as it is to bother about what it ought to be.

My father, James Howard-Wolferstan, emigrated to Ecuador in the early nineteen hundreds. He was, he said, the last of his line, and I have only heard of one other bearer of the name. He never told me why he left England. At any rate he was right to choose a small country where his flamboyant and kindly character would not be lost.

Ever since I can remember him he was the most dignified exhibit of Quito, dressed as if he were a fashionable clubman in a London June of 1908. But probably I underrate the formality of the time. Dressed, I should say, as if he were off for a week-end in the country during which he was likely to meet King Edward VII at lunch. Invariably he had a carnation in his buttonhole, and a white slip under his waistcoat. At race meetings and bull fights he would sport a grey top-hat. He would have nothing to do with the small British colony, but preserved proudly his British passport. So have I — or I shouldn’t be where I am.

He cannot have arrived in Ecuador with any capital, and I have no idea what the qualifications were - beyond personal charm - which permitted him to obtain the hand and dowry of my mother. Thereafter he lived a life of gracious idleness, buying and selling concessions on the eastern side of the Cordillera. He was always at ease with politicians - indeed I often think he might have been Vice-President of Ecuador if he had cared to surrender his nationality - and foreigners, especially North Americans, were impressed by his appearance and undoubted influence.

I loved my mother dutifully, what there was of her to love. She was his absolute opposite. Dressed in unrelieved and dusty black, she spent her days and nights creeping rapidly between the Convent of the Sacred Heart and the Cathedral. In early days there must - since I exist - have been occasional exceptions to this routine, but I remember none.

She would, of course, have been happily fulfilled in a nunnery, but her parents, who carried the blood of the Incas, preferred that their only daughter should increase the lay population rather than the clerical. I suspect that my father was far from their first choice as a son-in-law, but it was said that only he was persistent, perhaps over-persistent, in his attentions to her. Lest I appear unfilial, let me add that it was never said in my presence - or only once, and by my second cousin who was a lieutenant in the glorious army. I slapped his face and, though already under the civilizing influence of Oxford, shot him in the leg (I aimed for it, too) at the comically ceremonious meeting which followed. But I have no doubt that his libellous statement contained a certain element of truth.

My mother, poor dear, had little influence on my father and myself. I do not think she found any tragedy in that. She was entirely absorbed by the salvation of her soul - not selfishly, but in the firm belief that we could be saved from eternal torment by her prior arrival in the next world and her careful employment of political influence with its Authorities.

My father died two years ago. He had known for some time that his fate was on him, but never allowed me to suspect it. Only when his doctor told him it was that week or the next did he break the news to me, and then with the very minimum of solemnity between his first and second brandy.

When he saw that I was wholly overcome by sorrow - for in moments of extreme emotion I cannot help being as Latin as I am English - he told me to restrain myself and to relight my cigar. I can remember his exact words:

‘Everybody’s father has got to kick the bucket sooner or later,’ he said. ‘What’s so bloody astonishing about it? You’ll miss me for a month, I trust, and I’ll miss you for the next forty years or so - if there’s anything in all that stuff of your poor, dear mother’s, which I rather hope there isn’t.’

Then he told me that very little would remain for me after his death, and that the various companies of which he was chairman or president had only been kept in apparent prosperity by his reputation and the aid of a really clever auditor. We had lived well, and I would not have reproached him even if it had entered my head to do so.

‘The auditor will skip with his savings as soon as I am under the daisies,’ he assured me, ’and my advice to you is to follow him pronto. I’ve got a few hundred pounds in gold, and I want you to take them now. Book your passage home, and as soon as you’ve planted me - for I’d like you to be there - clear out before they start to settle up the estate.’

My father had never lied to me - though there were, of course, things which he found unnecessary to be described in detail. I therefore placed absolute trust in the story which he now told me, especially as it amused him. He was capable of being amused up to the end. His last conscious act, a fortnight later, was to wink at me.

‘I have never mentioned to you,’ he went on, ‘the old home of the Howard-Wolferstans, and I don’t propose to discuss it now. It was the manor of the village of Moreton Intrinseca. Go upstairs to the attics on the third floor. In my day a pack of servants used to sleep there, but from what I read in the English papers there won’t be many of them now and they won’t sleep under the tiles.

‘Turn to the right at the head of the staircase. The third door to the right leads into a small attic with a dormer window giving on to the parapet, and a fireplace. About three feet up the chimney you’ll find enough capital to settle you in any respectable business. My advice would be to look up your old Oxford friends and buy yourself a partnership in a firm of stockbrokers. But if you prefer a racing stable, that’s your affair.

‘And, whatever you do, don’t try burglary!’ he added. ‘Make friends with the present owner of Moreton Intrinseca. Stay a week with him. Marry his daughter, if you must. It doesn’t matter whom a man is married to, so long as he has enough money to keep his temper.’

His instructions, on their face value, belonged to a fairy tale, but I knew him: the mere fact that there was some sardonic jest which he hugged to himself made it certain that he was in earnest. He did not encourage me to question him, nor did I wish to. He had just told me that he was going to die, and attic chimneys were a wretched irrelevance. I only asked why on earth his money should still be there. He replied that he had good reason to think it was, and why wouldn’t it be? Even in his days no one ever lit a fire in the attics, and he was prepared to bet they hadn’t since. Early Victorian architects, he said, always built a fireplace, whether it was likely to be used or not. It was part of the room, like the wallpaper.