Fatal North (23 page)

Authors: Bruce Henderson

Tyson was shocked to learn that the men were still planning to strike out for Greenlandânext month, when they thought Disco would be due east and within reach, as they were told by their chosen adviser. They would not listen to reason or to anyone else. If they were risking only their own lives, the decision would have been bad enough, but the safety of the whole was imperiled, especially since they were determined to take the only boat. Having burned up one in their fires, they would not hesitate to appropriate the other.

On January 13, the thermometer stood at 40 degrees below zero. A gale came on for the next two days, bringing hope that it would open the ice for the hunters. When the wind abated three days later, the two Eskimos set off early for seals, which everyone prayed they would find.

Tyson recognized just how desperate their plight had become:

Jan. 16.1 hear a pleasant sound, because it is a promising one for water; the ice is pushing and grinding, which

will surely open cracks. It seems strange to think of watching and waiting with pleasure for your foundations to break beneath you; but such is the case. In our circumstances, food is what we most want; with enough seal meat we can face all other sorts of danger, but with empty stomachs we are ill prepared to meet additional disaster.

At eleven-thirty that morning, he heard a glorious soundâa life-inspiring shout. The natives were calling for the kayak. That meant they had found water, and water meant seals.

Tyson called to the men to get the kayak. They had not yet turned out from their igloo to begin the day, and a long time passed before there was any response to his call. Eventually, help came, and they carried the little boat about a mile, where they found Joe and Hans and, nearby, a dead seal floating in the water. Joe quickly paddled out and retrieved it, and the small party returned to camp in triumph.

Upon their arrival, Tyson directed the seal be taken into Joe and Hannah's igloo to be divided up. However, the Germans, led by John Kruger, one of the worst of the malcontents among the crew and a man whom Tyson had come to suspect was pilfering at least some of the stores, snatched the carcass and took it toward their own hut.

Tyson reached for his pistolâonly to discover he had left it in the igloo. At that moment he realized he would have gladly killed Kruger where he stood, no doubt triggering a fatal gunfight.

With such evil intentions being openly displayed by the men, and short fuses possessed by all, Tyson realized it might be impossible to save the partyâworthy and worthless alikeâfrom disobedience and lawlessness.

The men divided the seal to suit themselves, and the division went hard on the Eskimos and their families, the very men who had hunted day after day, in cold and storm, while these men lay idle on their backs or sat playing cards in the shelter of their igloos, mainly built by these same natives whom they wronged.

That night, Joe and Hans told Tyson that they had very

often suffered before for the want of food in the North, but they had never before endured anything like the present circumstances. The daily allowance was not enough to furnish heat or enable their bodies to resist the cold. Considering that they were outside battling the elements so much more than the rest, walking around and hunting, they really ought to be given a larger allowance of food. Tyson gladly would have, but he knew it would cause open mutiny among the armed men, destroying any semblance of harmony.

Jan. 17. The natives are out as usual, hunting for seal. They only got a small portion of the meat and a little blubber of the one last caught, the men keeping an undue proportion for themselves. This way of managing discourages the hunters very much; they labor, and see others consuming the fruits of it. But they dare not say much, for they are afraid for their lives.

How the last two dogs continued to live Tyson did not know.

Attempting to hunt for their own food, on January 16 they had a skirmish with a bear and came limping into camp somewhat disabled. Two days later, Joe found signs on the floe that one of the dogs had encountered two bears earlier that morning, and evidently had held them at bay for some time. One of the bears must have struck the dog, because he came bleeding into camp with a superficial wound that needed treatment. That bears were rising from the water and wandering on the floe was a good sign: seal must be close by. And if a big bear could be shot, it would provide a bountiful addition to their impoverished larder, but alas, the hunting was equally bad for man and beast.

On January 19, Joe saw a number of seals, but the wind was blowing heavily and it was very cold at the time. He tried to shoot the closest one, but he was shaking so with the cold that he could not hold his gun steady, and his fingers were so numb that he could not feel the trigger of the gun. The seal escaped.

Later that day, a great and unexpected event occurred: the sun reappeared after an absence of eighty-three days. The previous year, when they were on board

Polaris,

it had been absent for one hundred and thirty-five days, but they were far south of the previous year's winter quarters, so the sun had shown itself that much earlier.

Tyson happened to be the first to salute the rising orb. He had not been expecting it for several more days, and was therefore surprised as well as delighted. It was a blessed sight, giving happiness and renewed hope. The sun meant more than light to them, it meant better hunting, better health, relief from despondencyâhope in every sense now that their path to rescue would be lit.

When the English steward, John Herron, came out of his hut and saw the sun shining for the first time, he broke into an impromptu jig. Tyson realized that it was the first display of merriment on the ice floe, so destitute had been their situation.

After the sun dipped down about one o'clock that afternoon, Tyson thought he could again see, in the gathering darkness, land to the west.

An hour later, Meyer, a fount of all knowledge for his German brethren, announced that they had drifted within a few miles of the landâthat being the western coast of Greenland! And furthermore, they were exactly due west of Disco.

Meyer had a few navigational instruments; he had forbade anyone else from using them, and had even turned down Tyson's request to take his own readings. Nevertheless, Tyson was certain that the meteorologist was mistaken as to their position, whether due to his inexperience in these waters, inexactness of the instruments, or his mishandling of them.

The men became anxious again to try for Greenland.

“We should not pass Disco,” Meyer said. “No other place will suit us as well. There's food, tobacco, and rum there, left for us by

Congress

and already paid for.”

“We can take what we please!” added one of the men excitedly.

“Yes, indeed,” Meyer promised, as if the provisions left for the expedition by the U.S. Navy supply ship belonged personally to him.

“Listen to me,” Tyson said urgently. “Your lives depend on what I am to say. I have sailed these seas too often to be deceived about our course. As long as we are able to see land to the west, we cannot possibly be close to Greenland.”

Baffin Bay, he pointed out, was three hundred miles wide.

“Disco is a very high, rocky island,” Tyson went on. “You must recall that from our stop there. I have been there many times, and know all of the coast north and south of it well. Disco can easily be seen on a clear day at sea eighty miles distant.”

Tyson locked eyes with Meyer.

This arrogant self-professed “German count”âthis man of such questionable wisdomâhad caused Hall considerable trouble and been put down for it. Hall had had the power and authority to do so; Tyson did not. Since their commander's untimely death, the German element, including the doctor, had assumed more control over the expedition. Tyson did not know whether Meyer intentionally wished to make trouble for him or not, but his illusions and misinformation had that effect on the men, and everyone else on the floe whose lives depended on calm and rational judgment.

Had Meyer by whatever quirk of fate been left on

Polaris,

Tyson was certain that the German seamen would have behaved better, for they would not have had anyone to mislead them. His influence over them was considerable because they thought of him as educated, as a scientist, and because he was also their countryman, they fancied he took more interest in their welfare.

Tyson went on to tell the men that he wanted to get off the ice as badly as they, but that their chance of making landfall would be much improved if they waited until next month, then tried for Holsteinborg, the next Danish settlement down the coast, two hundred miles south of Disco. “Not only will the drift probably take us closer to Holsteinborg, but the weather and ice conditions will be better for travel by small boat.”

The men listened, then filed silently back to their hut.

Tyson had no idea what they would decide. But he knew if they opted for killing themselves through stubbornness and stupidity, they would in all likelihood doom the rest of the partyâmen, women, and childrenâwho had fought so hard to stay alive.

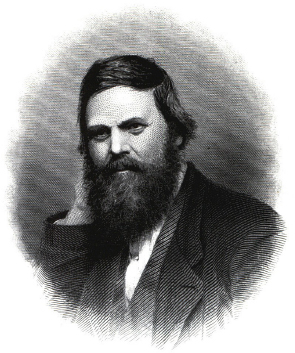

Charles Francis Hall, engraving based on the only known photograph of him, taken during the winter of 1870. (

From the collection of Chauncey Loomis

)

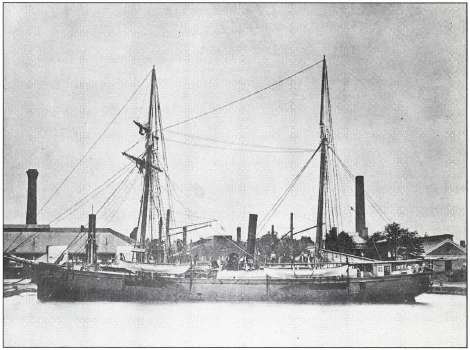

USS

Polaris

being fitted for her voyage to the Arctic at the Washington, D.C., Navy Yard. This is the only known photograph of the ship. (

Smithsonian Institution

)

George Tyson (

ARCTIC EXPERIENCES

, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1874

)

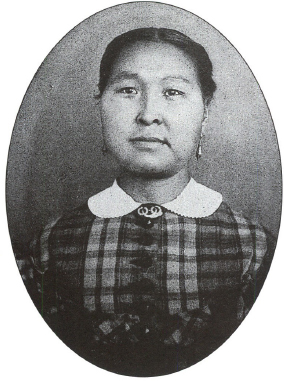

Hannah, “Tookoolito” (

NARRATIVE OF THE SECOND ARCTIC EXPEDITION COMMANDED Br CHARLES F. HALL

, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1879. From the collection of Chauncey Loomis.

)