Falling Pomegranate Seeds: The Duty of Daughters (The Katherine of Aragon Story Book 1)

Read Falling Pomegranate Seeds: The Duty of Daughters (The Katherine of Aragon Story Book 1) Online

Authors: Wendy J. Dunn

Copyright © 2016 Wendy J. Dunn

Kindle Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner.

M

MadeGlobal Publishing

More information on

MadeGlobal Publishing:

www.madeglobal.com

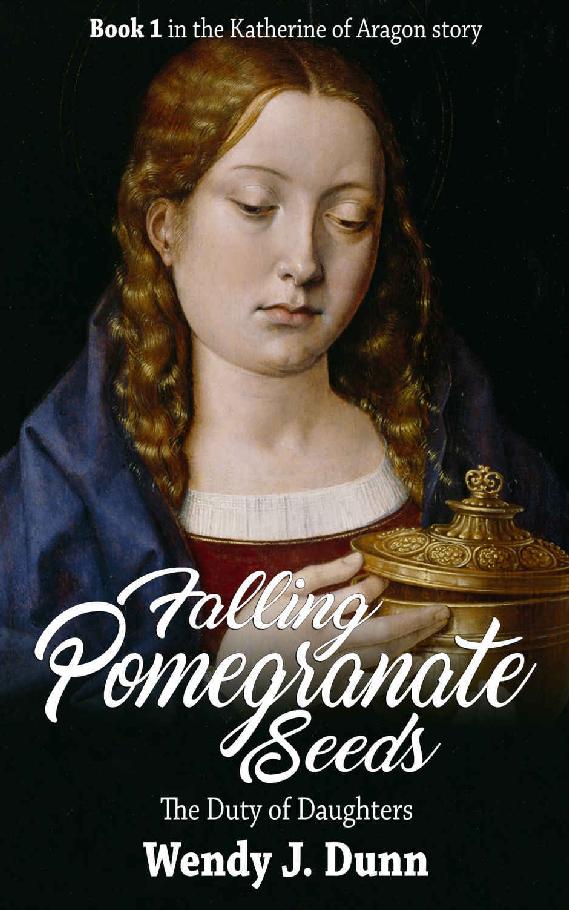

Cover

: Catherine of Aragon, as the Magdalene

by

Michael Sittow (circa 1469-1525)

Copyright © Detroit Institute of Arts, USA / Founders Society purchase, General Membership Fund / Bridgeman Images

I dedicate this novel to my first born, my beloved son, James. I am so proud and happy you now walk the same road I started walking so many years ago. May you discover what I have learnt – that teaching is a true privilege and calling, where our students teach us more than we can ever teach them.

Those who know, do. Those that understand, teach

~ Aristotle

Scholar

I cradle the books that found me.

Tonight, I prop them on my knees

one by one; each offering up

a lesson I must timely absorb.

The rain speaks of days like these,

in dim light, with only my wit as guide.

No feat of voluptuousness;

of womanhood, shall aid me here.

I tiptoe down these halls,

a quiet predator in the shadows,

light feet, steel-trap cunning,

and wily defiance; I shall show them

what a woman of iron mind can do

~ Eloise Faichney, 2016

(Once my student and now a dear friend, Eloise, with great joy, I watch you fly high.)

“That’s where the truth of history comes in,” said Sancho.

“They could as well have passed over such matters in silence out of fairness,” said Don Quixote, “for there’s no need to write down actions that neither change nor alter the truth of history if they must result in disesteem for the hero. In truth, Aeneas was not so merciful as Virgil paints him, nor Ulysses so prudent as Homer describes him.”

“That’s so,” replied Sancho, “but it is one thing to write as a poet and another as an historian: the poet can relate or sing things, not as they were, but as they ought to have been, and the historian has to write them, not as they ought to have been, but as they were, without adding or taking anything at all from the truth”

~ Miguel de Cervantes, from Don Quixote de la Mancha

Beatriz Galindo: (b? – 1534)

Years ago I discovered a footnote about this fascinating woman, known as

La Latina

(Lady of Latin), in an essay about Isabel of Castile. A Latin expert, poet, so knowledgeable about medicine, rhetoric and the philosophy of Aristotle, she tutored on the subjects at the University of Salamanca. Beatriz was also a friend and advisor to Queen Isabel, as well as being a wife and mother. She is yet another woman forgotten by history – and a woman who deserves notice. I hope she forgives my imagination for the liberties I have taken with her story in these pages, but if it makes people interested in finding out more about her, then I am happy. Beatriz was a student of Antonio Elio de Nebrija, a Renaissance scholar and a man known in history for writing one of the first books of grammar for a romance language.

Known as “the Artilleryman” during the war of Granada. Husband of Beatriz Galindo, Francisco Ramirez died in the taking of the Villa of Lanjaron in Granada, Spain.

Isabel ruled Castile from 1474 to 1504. My imagined construction of Isabel is drawn from these following works:

Isabel the Queen

:

Life and Times (

Peggy K. Liss); and

Isabel of Spain: The Catholic Queen (

Warren H. Carrol).

Ferdinand, Catalina’s father, was one of the rulers Niccoló Machiavelli used in

The Prince

as a benchmark for other rulers to follow. A wily fox and able politician, he made use of whatever he could, including members of his own family, to achieve his own ends. This influenced my imagination in the creation of his character. Machiavelli wrote: “...always using religion as a plea, so as to undertake greater schemes, he devoted himself with pious cruelty to driving out and clearing his kingdom of the Moors; nor could there be a more admirable example, nor one more rare” (Machiavelli 1532).

Isabel

(1470 – 1498)

Prince Juan

(1478 – 1497)

Juana

(1479 – 1555)

Maria

(1482 – 1517)

Catalina

, later Katherine, Queen of England (1485 – 1536)

Kinswoman of Catherine of Aragon

Dońa Josepha Gonzales de

Salinas

Don Martin de

Salinas

Ahmed

, son of Boabdil, King of Granada

Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros

Fray Hernando de Talavera (1428 – 1507)

Confessor to the queen

Margaret of Austria

Manuel, King of Portugal

Alcázar: palace

Amigo: friend

Andas: litter

Cadis: judges

Chopines: platform shoes

Converto: a Jew who becomes Christian

Dońa: Lady

Don: Lord

Hidalgo: Spanish noble

Habito: a loose day-gown

Hija: daughter

La Latina: The Lady of Latin

Prima hermana: first cousin

Si: yes

Toca: head covering

Uno Piqueño: little one

Corona_de_Castilla_1400.svg: Té y kriptonita. Based on Image:Conquista Hispania.svg de HansenBCN derivative work: Gabagool (Corona_de_Castilla_1400.svg) [CC BY-SA 2.5 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia

“Follow your star and you will never

fail

to find your glorious port,” he said to

me.

~ Dante Alighieri

Burgos, 1490

D

ońa Beatriz Galindo caught her breath and tidied her habito. She shook her head a little when she noticed ink-stained fingers and several spots of black ink on the front of her green gown. She sighed.

Too late now to check my face.

“The queen has sent for me,” she told the lone guard at the door of the chambers provided for Queen Isabel’s short stay at Burgos. The young hidalgo straightened his stance, then knocked once with the back of his halberd on the door, his eyes fixed on the white, bare wall across from him. The door opened and a female servant peeked out at Beatriz, gesturing to her to come in.

In spite of the hours since dawn, the queen sat in bed, her back against oversized cushions. She still wore her white night rail, a red shawl slung around her shoulders, edged with embroidery of gold thread depicting her device of arrows. A sheer, white toca covered her bent head, a thick, auburn plait falling over her shoulder.

Princess Isabel, a title she bore alone as the queen’s eldest daughter, and named for both her mother and grandmother, sat on a chair beside her mother, twirling a spindle. Her golden red hair was rolled and wrapped in a cream scarf criss-crossed with black lines, a wry grin of frustration formed dimples in her cheeks before she discarded the spindle in the basket at her feet with the others. She nodded to Beatriz with a slight smile. “Good morning, Latina,” she murmured, using the nickname bestowed on Beatriz by the queen. Beatriz hid her stained fingers behind her back and curtseyed her acknowledgement.

Straightening up, Beatriz gazed at the bed-hangings, unfurled behind Queen Isabel. A naked Hercules wrestled with a golden, giant lion, his club on the ground beside him. Turning to her queen, she fought back a smile and lowered her eyes, pretending little interest in Hercules, especially one depicted in his fullest virility.

Queen Isabel balanced her writing desk across her lap, scratching her quill against the parchment, writing with speed and ease. A pile of documents lay beside her. An open one, bearing the seal of the king, topped all the rest. Beatriz’s stomach knotted, and not just through worry. She closed her eyes and breathed deeply

. I am free; I am always free

while the king is elsewhere. Pray, it is not bad news about the queen’s Holy War.

The knot in her stomach became a roaring fire.

Holy War? Jesu’ – how I hate calling any war that. Pray God, just keep my beloved

safe.

She almost laughed out loud then; as one of the king’s most important artillery officers, Francisco Ramirez, the man Beatriz loved and had promised to marry, did not live to be safe but lived to live. It was one of the things that made her fall in love with him. Waiting to hear the reason for her summons, she gazed around the spacious bedchamber, composing in her mind the letter she would write to him tonight:

My love, my days are long without

you...

No – she couldn’t write that. If she did, it would be a lie. Her days were full – most mornings she spent tutoring the girls before relishing in the long afternoons free for her own studies. She missed Francisco, but still lived a rich life without him, a richer one when he was at court.

What to write to him then? She could not tell him of her hatred of the Holy War. She could never name as holy a war stamping out any hope of another golden age, when Jews, Moors and Christians lived and worked together in peace. Francisco was a learned man, but a man who used his learning to win this war. Her learning taught her otherwise. It taught her to keep silent about what she really felt to protect the freedoms of her life. Could she tell him then of her joy of teaching the infanta Catalina and her companion Maria de Salinas? For six months now she had been given full responsibility for their learning. She looked at the queen. Surely the queen was happy with the infanta’s progress?

As if Beatriz had spoken out her thought aloud the queen said, “I want to speak to you about my youngest daughter.” She waved a hand to a nearby stool. “Please sit.”

The queen put aside her quill and pushed away her paperwork. She lifted bloodshot, sore-looking eyes. A yellow crust coated her long, thick lashes.

Seated on the stool, Beatriz gazed at the queen in concern. If there was no improvement by tomorrow, she would prepare a treatment of warm milk and honey for her eyes, even at the risk of once again upsetting those fools calling themselves the queen’s physicians.

“Si, my queen?” she murmured.

“Tell me, how do you find my Catalina and our little cousin Maria?”

Beatriz began breathing easier. Just another summons to do with the infanta’s learning. “Both girls are good students, my queen,” Beatriz smiled. “The infanta Catalina is a natural scholar. She relishes learning – even when the subject is difficult, but that does not surprise me. Your daughter is very intelligent, just like her royal mother. Maria too, is a bright child. Slower than the infanta, but already the child reads simple books written in our native tongue, as well as some Latin. The method of having books written in Latin and Castilian placed side-by-side is working well.” Beatriz straightened and lifted her head. “It was the method used to teach me when I was the same age as the infanta.”

The queen exchanged a look with her listening daughter.

“I have been pleased to see how much my Catalina, my sweet Uno Piqueño, enjoys her mornings with you.” Queen Isabel brought her hands together, drumming her fingertips together for a moment. “Latina, I believe the infantas Juana and Maria can be given over to other tutors now that you have provided them with an excellent grounding in Latin and philosophy, but I desire you to be Catalina’s main tutor, of course that includes Maria, her companion.” Queen Isabel twisted the ring on her swollen finger.

“One day, my Catalina will be England’s queen. It will be not an easy task – not in a country that has known such unrest for many, many years. I want to make certain my daughter is as prepared as I can make her, but I need your help. Can I rely on you to stay with us, and teach Catalina what she needs to know of England’s history, its customs, its laws?”

“My queen, of course...” Beatriz halted her acceptance when the queen raised her hand.

“Think before you commit yourself. You are betrothed. What will happen when you are wed and, God willing, have the blessing of children? We talk of an obligation of at least ten years, and for you to be not only my daughter’s tutor, but act also as her duena.”

Beatriz smiled at Queen Isabel. “Francisco and I are both your loyal servants. When the time comes, we will do what needs to done for our marriage and children, but I will confess to you that my real life is here, and as a teacher at the University of Salamanca. I am honoured that you wish me to continue in that role for the infanta. And to be entrusted with teaching your daughter, now and in the future... my queen, words can not describe what that means to me.”

···

Light. So much light.

Beatriz Galindo walked back to the library in light, and not just the light from the high archways of the royal alcázar. It was the light of life. Her life. Before the shadows engulfed her again, one archway opened to a garden where running water from a fountain sparkled like diamonds, light and water flashing rainbows onto the high, white stone walls. Beatriz halted by the arch, holding her habito away from her feet, and gazed out before treading into the garden. She sat on a stone bench and looked around her.

At summer’s end beauty and ugliness competed for dominance. Most of the flowers were now gone to seed, even the well-tended roses drooped their heads, crimson petals and desiccated leaves of every shade of brown scattering upon an earth sucked dry and cracked by days of relentless heat. Life passed so quickly, one season dying, re-birthing into another.

Beatriz closed her eyes for a moment, raising her face to the sunlight.

Dear God, I have much to give thanks for – I will always be grateful for what I’ve been given.

Then she thought how complicated was this gratitude. It was a gratitude birthed from sorrow, and from loss.

A shadow fell upon her. She opened her eyes, relieved to see her dearest friend, Josepha de Salinas, smiling down at her. “You are fortunate, Beatriz, to have time to enjoy the day. I am on my way to the queen.” Josepha laughed a little. “My royal cousin has summoned me to embroider the hems and collars of her new shifts. Sometimes I wish my mother had not taught me so well my skills with the needle. I may then be like you, amigo, more at liberty to spend my mornings in the garden.”

The sheer, white fabric of Josepha’s toca wafted in a breeze against the sides of her face. Apprehension stabbed Beatriz. Her friend’s face was too pale, too thin. The deep hollows under her high cheekbones were as if strong thumbs had bruised her wan skin. A flowing black habito revealed the swell of her belly, a jewelled scallop, made of gold, gathering together the points of the toca at the breast of her gown. Beatriz did not need her knowledge of medicine or midwifery to know that Josepha’s pregnancy was proving difficult. Beatriz swallowed, thinking of what she could make to help her friend. Hiding her anxiety, she smiled at Josepha. “I was thinking of my own mother.”

Josepha sat beside her. “Did she not die when you were but a child?”

“Si – I was three when the black death took her. My father never forgave himself that he could not save her from suffering a terrible death. I think I have told you that my father was a famous scholar of medicine, highly regarded in all Castilla – yet all his knowledge proved useless at that time. I was just wondering how different my life would have been if my mother had lived. My father’s grief was such he never married again. It no longer mattered that I was but a daughter. He consoled himself by teaching me.”

Josepha laughed. “And found himself with a prodigy.”

“Prodigy?” Beatriz shrugged. “I’m not certain I was ever that. Rather a child with a great passion for books and learning. I was twelve when my father’s great friend Antonio de Nebrija took me under his tutorage. It changed my destiny from that of a religious order to a respected teacher of Latin at the university itself. So respected Queen Isabel sought me out when I was twenty to teach her to read and speak Latin. I have found complete fulfilment these past five years and more – not only as a teacher at Salamanca, but in my work as tutor to the queen’s children.” Beatriz lifted her gaze to a rose dropping its petals.

Si. Death not only destroyed the life I had then, but also planted the seeds for the life I have now. The life I was meant to live.

She refused to ponder about the dues she sometimes paid.

“You have told me the story before. But what makes you think of this now?” Josepha asked.

“I am happy today – the queen wants me to continue as tutor to her youngest child, and your daughter.”

Josepha lifted her dark eyebrows, and grinned wryly. “So – I hear it first from you.”

Beatriz eyed her friend. “Do you mind?”

“Does it matter if I mind, or not? Martin or I could not say no to the queen when she asked for Maria to grow alongside her daughter as her companion. It was a great honour for our family – and all of us saw how much the young infanta loved Maria. We are close kin, after all, with the queen. I must accept with good grace my daughter shares the same education as the infanta.” Josepha glanced towards the archway leading back into the building. “While I would like to sit and talk with you in the sunshine, I must be away if I have any hope of finishing even one of the queen’s chemises before the day grows too hot.”

Josepha stood up, shook out the folds of her habito and headed towards the sunlit corridor. “No doubt I will see you soon enough,” she called over her shoulder.

Beatriz watched her friend go. For a time she sat there, content to be alone with only her thoughts as company, content this sunlit garden held no dark memories for her. At last, she sighed and rose from the bench, heading towards the library. Almost at its door, she heard voices of children. She slipped into the alcove that hid her from view but also allowed her to look into the room.

Catalina and Maria bent their heads over a book, opened wide upon Maria’s lap. The girls sat in a pool of light from the window behind them. It burnished their hair with gold – lighting Catalina’s to a fiery red and covering Maria’s black hair with a veil-like sheen. Even at only five, both girls took great care of precious books

. But where is Dońa Teresa Manrigue?

She should be here.

A tender-hearted woman, Dońa Teresa carried in her pocket a seemingly endless supply of rose sugar as rewards for the children. The last time Dońa Teresa left the girls alone in the library she had told Beatriz the infanta had commanded her to go. No wonder the queen desired a new duena for her daughter.

“My turn to be Arthur!” Maria said, placing her finger on the page closest to Catalina. Her face a picture of concentration, Maria licked her top lip. “And as they rode, Arthur said, I have no sword.” Maria’s sigh was one of clear relief.

Catalina pulled the book closer to her. “No matter, said Merlin, hereby is a sword that shall be yours.”

Beatriz restrained a laugh, hearing the infanta deepen her already low voice. But while one child loved learning, the same couldn’t be said about the other. When Catalina pointed to the next passage there was no mistaking Maria’s discomfort as she shook her head. “You do it. You read better.”

Catalina’s grin revealed missing milk teeth, giving her round face an endearing look. “I only try harder.”

“You forget,” Maria said quietly, glancing towards a hoop with an uncompleted embroidery some distance away, “Mama doesn’t care whether I read or not.”

Catalina turned to Maria a look of determination, it was one that mirrored the queen’s. Just like her mother, altering the girl’s chosen course was nigh on impossible. “I do,” Catalina said. “I want you to be as good as me at this. Think, when we learn about herbs from Latina and the good sisters, you can go to my mother’s library to know more. Latina says knowing Latin is like having a key that will open many doors. You read now.”