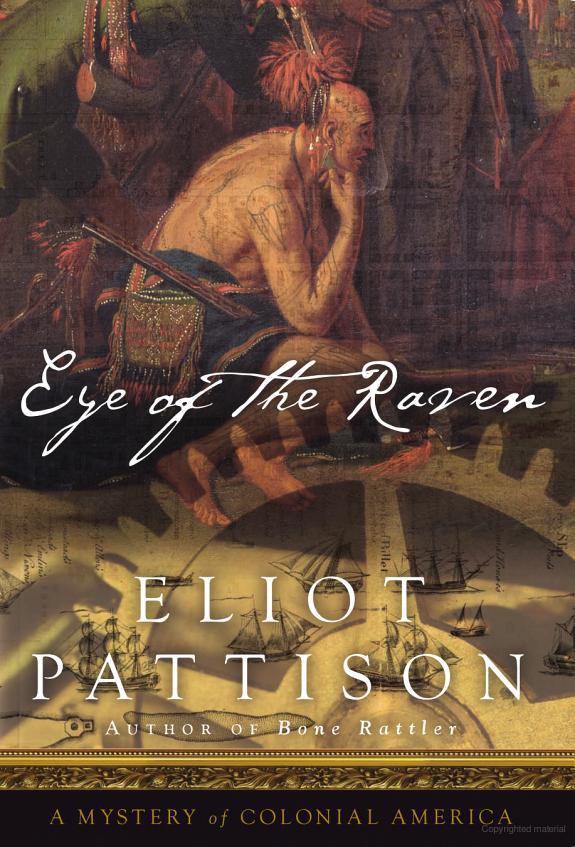

Eye of the Raven

ELIOT PATTISON

For Connor, who nourishes my muse.

April 1760

The Pennsylvania Wilderness

HEY WERE ON the bloodiest ground of a bloody war, and neither side in the great global conflict was inclined to show mercy. With every step the old Indian took through the sleeping enemy camp, Duncan McCallum's heart rose higher in his throat. He had begged Conawago to stay away from the enemy bivouac, had promised he would come back with him on the next full moon, but his companion would not wait. It mattered little to him that the Hurons camped with the French below would roast him alive if they found him stalking through their camp. The spirits had placed their enemy there to test his resolve, Conawago had insisted, and he had begged the young Scot not to accompany him. He had not a moment to spare in his quest to save the tribes, and his mother had taught him that the sacred ochre he needed from the ledge by the camp was at its most powerful when harvested under the full moon.

HEY WERE ON the bloodiest ground of a bloody war, and neither side in the great global conflict was inclined to show mercy. With every step the old Indian took through the sleeping enemy camp, Duncan McCallum's heart rose higher in his throat. He had begged Conawago to stay away from the enemy bivouac, had promised he would come back with him on the next full moon, but his companion would not wait. It mattered little to him that the Hurons camped with the French below would roast him alive if they found him stalking through their camp. The spirits had placed their enemy there to test his resolve, Conawago had insisted, and he had begged the young Scot not to accompany him. He had not a moment to spare in his quest to save the tribes, and his mother had taught him that the sacred ochre he needed from the ledge by the camp was at its most powerful when harvested under the full moon.

Duncan watched in abject fear as Conawago slipped between the French officers' tents, then stepped past one sleeping form after another, his linen shirt lit like a beacon in the moonlight. As he leaned forward from the shadows Duncan saw that his friend's hand gripped not the war ax at his belt but the amulet that hung from his neck. A man with blond locks stirred near the smoldering fire as Conawago passed by. The long rifle in Duncan's hand flew to his shoulder, and he kept the figure in its sights until the French soldier settled back into his blanket.

The haunting call of a whippoorwill rose from the opposite side of the camp, where Duncan had last seen the Huron sentry. Suddenly a second bird answered, much nearer, sending Duncan back against a tree, every muscle tensed, every nerve on fire. He had not expected a second sentry, but now knew there was one, near the rock face that was Conawago's destination. Duncan bent low and with slow, stealthy strides eased through the mountain laurel. Not many months earlier he would have thrashed about like a lost cow in the undergrowth, would have been dead after his first few steps so close to the enemy. But after so many months with him in the wilderness Conawago had proclaimed he was no longer a Highland Scot, but a woodland Scot.

The tall, muscular Huron stood in the brush, watching not the camp but the forest, his back to Duncan, his head cocked as if he had sensed something in the deep shadows of the woods. Duncan's heart hammered in his chest as he silently lifted his tomahawk. If he did not disable the guard in one blow the alarm would be spread. But as Duncan raised his arm the sentry suddenly gasped in pain, clutching at his head, then was jerked violently downward, disappearing into the brush. Duncan heard a low moan then a faint rustling of leaves that could have been the sound of something scurrying away.

The sentry was unconscious when Duncan reached him. A dozen frantic thoughts raced through his mind, that one of the nocturnal predators of the forest was stalking them, that they had stumbled into a nest of poison vipers, that he and Conawago were about to be trapped in a battle between the Hurons and their blood foes the Iroquois. Then he saw his friend had reached the exposed ledge that held the ochre. He choked down his fears and rushed to help Conawago extract the sacred yellow powder.

But though he had reached the rock face, his companion was not digging the ochre. With two dozen bloodthirsty enemies before him he was on his knees, arms outstretched at his waist, palms upward, speaking softly to the moon.