Exodus From Hunger (6 page)

Read Exodus From Hunger Online

Authors: David Beckmann

Tags: #Religion, #Christian Life, #Social Issues, #Christianity, #General

JEROME SARKAR

When I think about hopeful trends in developing countries, I think of my friend Jerome Sarkar. My wife Janet and I spent most evenings with him when we were working in northwest Bangladesh many years ago. Jerome was my colleague on the staff of the Rangpur Dinajpur Rural Service, a grassroots development agency that Lutheran churches around the world support.

Bangladesh had just been through its war of independence from Pakistan. The U.S. secretary of state at the time, Henry Kissinger, predicted that Bangladesh would always be an “international basket case.” But the proportion of Bangladesh’s population in poverty has dropped since its independence from 70 percent to 40 percent. Literacy has more than doubled, and child mortality is less than half of what it was. Bangladesh has maintained economic growth and democracy since the early 1990s.

12

Jerome kindly sent me his thoughts on how his own life has intertwined with his nation’s progress against poverty.

In 1945 my father fell seriously ill and died at the age of thirty-eight. Our mother with her five children was at a loss. Nothing could save us without intervention of Almighty God and we were praying to Him for His mercy. An American priest, Father Norkauer, appeared as God’s angel and arranged to put us in an orphanage.

His sister later funded my education at Holy Cross High School. The priests who ran the school also helped poor people from time to time with food, medicines, and money. This made a big impression on me.

I took a position in a pharmaceutical company and completed my bachelor’s degree attending a local college on the night shift. I then married my wife Maria and started family life.

In the early seventies, Bangladesh was in political turmoil. At the beginning of the liberation war, we had to flee and take shelter in a village. Due to lack of law and order, common men like us were passing our days in helpless conditions. The company where I was working also suffered a setback in business. During the postwar turmoil, nepotism and corruption were the rule of the day. Because of abuses within my company, I decided to leave.

Through a friend, I approached the director of Rangpur Dinajpur Rural Service (RDRS) and joined the organization in 1975. I helped to manage a grassroots construction program in northern Bangladesh. If villages would provide labor and local materials, RDRS would help them build a school or a culvert for a local road. Besides fulfilling my official responsibilities, I helped RDRS staff members form a cooperative credit union for their own self-advancement. I eventually moved to the RDRS office in Dhaka and then retired from full-time service in 1995.

My wife Maria left this earthly abode for eternity in 1993. Maria and I were blessed with four children. My youngest son Hubert died while doing his master’s in structural engineering. My eldest son, a master’s in economics, is serving in a commercial bank as an executive. My second son, a master’s in statistics, is a professor in a leading college, and my daughter, a bachelor’s in arts and education, is a teacher in a school. My daughters-in-law are also master’s degree holders. In a country like Bangladesh, I have enough ground to be happy.

I started my life in poverty and now, though not a moneyed man, I am contented. I have been enriched by life’s experiences through thick and thin. Faith in my Creator, courage to accept help from friends, and a growing sense of responsibility toward others have led me to meaningful living and satisfaction.

Looking back, I offer these observations:

Poverty is not a curse. Poverty brings us closer to Almighty God. Bangladesh is home to millions of poor people, and the poor know that God is with them. Who else do they need?

Friendship between the wealthy and the poor can benefit both. The wealthy can help the less fortunate better their living condition and, in the process, find meaning as a worker in God’s plan.

Bangladesh was known by the whole world as the poorest of the poor. Despite many flaws even today, Bangladesh has made tremendous strides toward development over the years.

The United States was always considered the most powerful and wealthy nation. Americans always had their say about the poverty, backwardness, and human rights conditions in other countries. Nobody ever dared to talk about them. Interestingly, today, even in Bangladesh, conscious groups talk about poverty in America, human rights violation by Americans, and underdevelopment in certain sections of the American community. Yet the process of introspection has started, and some Americans are taking steps to veer the ship to the right direction for the U.S.A. and the globe at large.

Poverty in the United States is not nearly as severe as poverty in Bangladesh. Most poor Americans have amenities that would qualify them as middle class or better in Bangladesh: running hot and cold water, a toilet and shower, a television, a telephone, and access to public roads, schools, and hospitals. Yet poor people in the United States suffer hunger, disease, economic anxiety, indignity, poor schooling, and violence.

The United States used to be a powerful poverty-reduction machine. My own great-grandparents homesteaded in Nebraska. They and their children lived simple lives and sometimes suffered deprivation, but they worked hard and prospered. My parents’ generation went through the Depression and worked sacrificially to get ahead. I grew up surrounded by comforts and opportunities that my grandparents couldn’t have imagined.

Most American families have experienced similar improvements in living standards. In 1900, about 40 percent of all Americans were poor. That declined to 25 percent in the mid-1950s.

13

The poverty rate declined further in the 1960s and early 1970s, and has fluctuated between 11 and 14 percent since 1973.

Economic growth drove most of the nation’s past progress against poverty, but government programs also helped. The Homestead Act gave my great-grandparents their farmland. The development of public schools and colleges set the stage for my mother and father to improve their lives. The great majority of their generation was able to finish high school, and my father went to college and graduate school at the University of Nebraska, a public land-grant institution.

During the New Deal and the Second World War, government policies and organized labor combined to create a broad middle class. During that period the rich got poorer, while workers got considerably richer.

14

After the Second World War, the GI Bill gave a huge boost to many people.

The historical experience of African Americans and other people of color has been very different. African Americans endured slavery and then legalized segregation and discrimination. Native Americans were forcibly removed from their lands. Racial and ethnic minorities still have to cope with prejudice and discrimination in employment, housing, and social life. They suffer much higher rates of hunger and poverty than the white majority.

The civil rights movement of the 1960s ended many systems of discrimination and gave African Americans the right to vote. The civil rights movement and the Black Power movement of the late 1960s also helped convince the country to expand antipoverty programs during the Johnson and Nixon administrations.

President Johnson’s Great Society programs have been much maligned. President Reagan later quipped that “we declared war on poverty, and poverty won.” But, in fact, the Great Society programs played an important role in reducing poverty in the 1960s and early 1970s.

President Nixon ended some of Johnson’s programs, notably those that helped poor people gain power through publicly funded lawyers and community organizations.

15

But the Nixon administration continued and expanded others. Nixon’s expansion of the national nutrition programs, for example, eliminated the kind of malnutrition we now associate with poor countries. A team of doctors supported by the Field Foundation studied hunger in poor parts of the country in the late 1960s and then made return visits ten years later. Their second report noted great strides against hunger:

In the Mississippi delta, in the coal fields of Appalachia and in coastal South Carolina—where visitors ten years ago could quickly see large numbers of stunted, apathetic children with swollen stomachs and the dull eyes and poorly healing wounds characteristic of malnutrition—such children are not to be seen in such large numbers.

16

Programs for elderly people that expanded in the 1960s were also maintained. Between 1959 and 1980 the proportion of elderly people in poverty dropped from 35 percent to 16 percent, almost entirely due to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

17

Yet, at the same time, the structure of the economy was starting to change in ways that would make it harder for unskilled people to provide for their families. Technology and knowledge were becoming more important in the economy, depressing incomes for workers without much education. In order to guard against inflation, our nation stopped trying to keep unemployment as low as it was in the 1960s. Competition from developing countries also had some negative effect on the wages of low-skilled workers in this country. Finally, the importance of labor unions has declined. These shifts combined to depress the average wage of unskilled workers, which is now a third lower than it was in 1970.

18

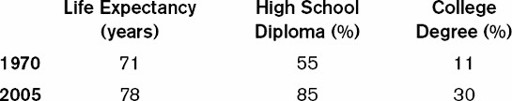

U.S. health and education have continued to improve:

19

The poverty rate declined again during the Clinton administration. The country enjoyed exceptional peace and prosperity during those years, and President Clinton made a strong economy his priority. He also expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit for low-income workers.

But progress against poverty has not been sustained. The poverty rate has gone up and down over the last several decades, correlated closely with the rate of unemployment. We should not be surprised. Think about our presidents since 1974: Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan (two terms), George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton (two terms), George W. Bush (two terms), and Barack Obama. Reducing poverty has not been a top priority for any of these administrations. Other problems and voter concerns have always taken precedence.

I sometimes do interviews with journalists from developing countries, and they are usually bewildered that a country as rich as the United States still puts up with widespread hunger and poverty. Arguably, the kind of poverty that persists in the United States is harder to overcome than mass poverty in developing countries. In poor countries, nearly everybody is poor. The provision of schools, roads, and improved technologies allows the population as a whole to raise its standard of living. In a highly developed country like the United States, the population that remains poor includes a higher proportion of people with physical or mental disabilities. On the other hand, the United States has vastly more resources from which to draw in dealing with these problems. The average income of people in this country is higher than almost any place else in the world, and U.S. economic output per person has more than doubled since 1970.

20

The U.S. government’s data on food insecurity allows us to guesstimate how much it would cost to end food insecurity in the United States. We know from the official data that the extra groceries needed to make all families food secure would cost roughly $34 billion a year (in a time of normal employment). Expanding SNAP or the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) would not get groceries precisely to the families that need them. But we might use, say, $50 billion as an order-of-magnitude estimate of what it would cost to end food insecurity in the United States through food assistance programs once the economy recovers.

Just providing food to food-insecure households would not be the best way to end food insecurity. It would be better to complement food assistance with initiatives that would help food-insecure families work their way out of poverty. But the $50 billion figure provides a rough sense of what it might cost to end food insecurity in the United States.

The $50 billion guesstimate, together with the $33 billion estimate of what it would cost for the United States to do its part to achieve the Millennium Development Goals, shows that the costs of dramatic progress against hunger and poverty are not prohibitive.

The United States spent $190 billion on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in 2008. The Bush tax cuts are costing the United States about $150 billion a year.

21

Americans spend $48 billion a year on food and care for our pets.

22