Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (74 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

a.

A

pressure-loaded

(hyperdynamic, systolic overloaded) apex beat is a forceful and sustained impulse (e.g. in aortic stenosis, hypertension).

b.

A

volume-loaded

(hyperkinetic, diastolic overloaded) apex beat is a forceful but unsustained impulse (e.g. in aortic regurgitation, mitral regurgitation).

Don’t miss the tapping apex beat of mitral stenosis (a palpable first heart sound) or the dyskinetic apex beat caused by a previous large myocardial infarction. The double or triple apical impulse in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is very important too. Feel also for an apical thrill and time it.

10.

Palpate with the heel of your hand for a left parasternal impulse, which indicates right ventricular hypertrophy or left atrial enlargement. Now feel at the base of the heart for a palpable pulmonary component of the second heart sound (P2) and aortic thrills. Percussion is usually unnecessary.

11.

Auscultation begins with listening in the mitral area with both the bell and the diaphragm. Spend most time here. Listen for each component of the cardiac cycle separately. Identify the first and second heart sounds (see

Table 16.4

) and decide whether they are of normal intensity and whether they are split. Now listen for extra heart or prosthetic heart sounds (see

Table 16.4

) and murmurs (see

Table 16.5

). Mechanical valves include bileaflet, ball case and tilting disc. Ball case valves have a sharp opening sound and may rattle. Tilting disc valves have soft opening sounds and sharp closing sounds. All mechanical valves require anticoagulation. Biological valves may have a systolic murmur; anticoagulation is not required. Do not be satisfied at having identified one abnormality. However, remember it is quite common to get simple rather than complex lesions in the examination.

Table 16.4

Heart sounds

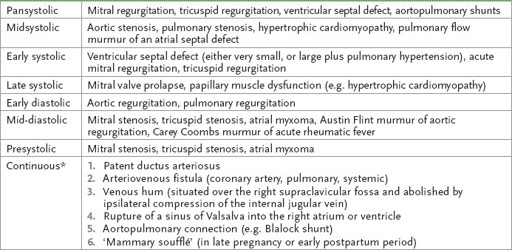

Table 16.5

Differential diagnosis of murmurs

*

Aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation or mitral stenosis and mitral regurgitation may be confused with a continuous murmur.

12.

Repeat the approach at the left sternal edge and then at the base of the heart (aortic and pulmonary areas). Time each part of the cycle with the carotid pulse. Listen below the left clavicle for a patent ductus arteriosus murmur, which may be audible here and nowhere else.

13.

It is now time to reposition the patient, first in the left lateral position. Again feel the apex beat for character (particularly tapping). Auscultate carefully for mitral stenosis with the bell. Next sit the patient forward and feel for thrills (with the patient in full expiration) at the left sternal edge and base. Then listen in those areas, particularly for aortic regurgitation.

14.

Dynamic auscultation should always be done if there is any doubt about the diagnosis. The Valsalva manoeuvre should be performed whenever there is a systolic murmur, otherwise hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is easily missed (p. 330).

HINT

The patient who seems familiar with the Valsalva manoeuvre may well have a murmur affected by it.

15.

The patient is now sitting up. Percuss the back quickly to exclude a pleural effusion (e.g. due to left ventricular failure) and auscultate for inspiratory crackles (left ventricular failure). If there is radiofemoral delay, also listen for a coarctation murmur here. Feel for sacral oedema and note any back deformity (e.g. ankylosing spondylitis (p. 405) with aortic regurgitation).

16.

Next lay the patient flat and examine the abdomen properly (p. 358) for hepatomegaly (e.g. as a result of right ventricular failure) and a pulsatile liver (tricuspid regurgitation). Perform the hepatojugular reflux test. Press over the upper abdomen for 15 seconds or so and watch for a rise in the JVP. This is a reliable sign of heart failure. Feel for splenomegaly (endocarditis) and an aortic aneurysm. Palpate both femoral arteries. Then examine all the peripheral pulses. Look particularly for peripheral oedema, clubbing of the toes, Achilles tendon xanthomata (

Fig 16.7

), signs of peripheral vascular disease and the stigmata of infective endocarditis.

FIGURE 16.7

Xanthomata. P Durrington. Dyslipidaemia,

Lancet

, 2003. 362:717–731.

17.

At the end, ask the examiners for the results of the urine analysis (haematuria in endocarditis) and a temperature chart (fever in endocarditis), and examine the fundi (for Roth’s spots (

Fig 16.8

) in endocarditis and for hypertensive changes).

FIGURE 16.8

A retina showing cotton wool spots, retinal haemorrhage and Roth’s spot in a septic bactereamic cancer patient. I Celik, M Cihangiroflu, T Yilmaz. The prevalence of bacteriaemia-related retinal lesions in seriously ill patients.

Journal of Infection

, 2006. 52(2):97–104, Fig 1.

Note

•

It is fairly unlikely that you will have time to complete all aspects of your examination. If you are stopped, mention the list of things you would still like to do that are particularly relevant.

•

If you have auscultated and there is nothing obvious at first, consider the following and exclude them:

1.

mitral stenosis (see

Fig 16.9

) (position and exercise if necessary)

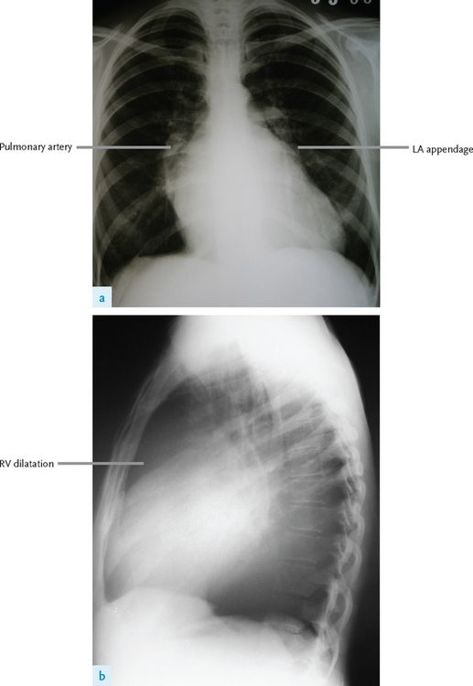

FIGURE 16.9

(a) and (b) Mitral stenosis on PA film. The left atrial appendage is dilated and there are prominent pulmonary arteries. The heart appears enlarged because of right ventricular enlargement, which is more obvious on the lateral film. Figures reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

2.

atrial septal defect (listen carefully for fixed splitting)

3.

mitral valve prolapse (perform a Valsalva manoeuvre)

4.

pulmonary hypertension (see below)

5.

constrictive pericarditis.

Notes on valve diseases

After you have made a diagnosis of a valve lesion, the following are the types of facts you should know. An assessment of the lesion’s severity is usually required.

Candidates should be able to make some recommendation as to appropriate follow-up. Most patients with valve abnormalities should be reviewed regularly and have repeat echocardiograms. For patients with mild abnormalities about every 3–4 years is sufficient, but for more severe cases annual review is usually recommended. Patients who are not symptomatic but have severe disease may need 6-monthly review, usually with a repeat echocardiogram. Patients should be advised to return for earlier review if symptoms (e.g. dyspnoea, chest pain or exertional dizziness) occur.

Mitral stenosis

Valve area: normal, 4–6 cm

2

; severe mitral stenosis, <1 cm

2

.

CAUSES

1.

Rheumatic (in women more often than men).

2.

Congenital very rarely (e.g. parachute valve, with all chordae inserting into one papillary muscle).

CLINICAL SIGNS OF SEVERITY

1.

Small pulse pressure.

2.

Early opening snap (owing to raised left atrial pressure).

3.

Length of the mid-diastolic rumbling murmur (persists as long as there is a gradient).

4.

Diastolic thrill at the apex (rare).

5.

Presence of pulmonary hypertension, the signs of which are:

a.

prominent

a

wave in the JVP

b.

right ventricular impulse

c.

loud pulmonary component of the second heart sound (P2); a palpable P2 is more helpful

d.

pulmonary regurgitation

e.

tricuspid regurgitation.

RESULTS OF INVESTIGATIONS

1.

ECG:

a.

P

mitrale in sinus rhythm

b.

atrial fibrillation (a sign of chronicity)

c.

right ventricular systolic overload (severe disease)

d.

right-axis deviation (severe disease).

2.

Chest X-ray film (see

Fig 16.9

):

a.

mitral valve calcification

b.

big left atrium:

i.

double left atrial shadow

ii.

displaced left main bronchus

iii.

big left atrial appendage

c.

signs of pulmonary hypertension:

i.

large central pulmonary arteries

ii.

pruned peripheral arterial tree

d.

signs of cardiac failure.