Everything Is Wrong with Me (9 page)

Read Everything Is Wrong with Me Online

Authors: Jason Mulgrew

Of course, my mother would cry at graduation when, during my valedictorian speech, I announced that I was turning down the big baseball schools and instead choosing the academic scholarship to Harvard, where I could both make her proud in the classroom and lead their once-proud but now-faltering baseball program back to glory. And of course, that is exactly what I would do. After an 0-28 season the year before, the team would finish with a 26-2 record in my freshman year (one loss coming when I had to play the entire outfield by myself because my teammates were involved in a minor bus accident and the other when I was momentarily hampered with dysentery; even in my fantasies I was a hypochondriac). We would never lose again on my watch.

After my freshman year, the Phillies, Yankees, Mets, Red Sox, and pretty much every major-league team would come calling with offers of big money, fast cars, and loose women. But I’d brush them all aside because I had another dream to attend to first. In addition to being a stellar athlete, I’d be an equally stellar student. And for my honors thesis, I’d have an ambitious goal to perform the first ever heart-liver double transplant—

in front of a live studio audience

. It would be a success, and afterward three girls would make out with me at the same time, thus concluding my college career.

And then on to the majors. You know how the rest of the story goes. First overall pick by the hometown Philadelphia Phillies. A rookie year featuring the Rookie of the Year Award and a World Series championship, earning me the nickname Jason “Midas” Mulgrew, since everything I touched turned to gold. Then sixteen Gold Gloves, eight MVP awards (the writers would eventually turn against me), almost 800 home runs, and a career .340 average. Later, I’d be up there on the podium at the Hall of Fame, giving my speech. It would be similar to the speech that I’d given to the Nobel Prize people only a year before, but more about baseball and less about peace/medicine/literature/physics/general awesomeness. I’d look at my mom and dad and thank them for all their support over the years. They’d smile and nod with appreciation, and then look at my brother (the convict) and my sister (the telemarketer) and shake their heads in disapproval. Then I’d look at my wife, Cindy Crawford, and thank her for always being there for me, through all the wins and losses, slumps and hitting streaks. She’d smile and wink, and I’d blush. Then Cindy and I would go back to the hotel and do whatever it was that a guy and a girl did when they were in a hotel room together.

So surely I would take to Little League very quickly. This wasn’t even in question. I had never played fast-pitch hardball before, but I wasn’t concerned with this.

No one

I knew played fast-pitch hardball, because that required resources that we didn’t have access to. For one thing, grass and open space were both pretty hard to come by on Second Street. If we were feeling ambitious, my friends and I could head down to “the Rec,”

*

the park down at Third and Shunk that had two baseball fields, some basketball courts, a public pool, and a lot of grass. But going to the Rec was a ballsy move, because we ran the risk of being hassled or picked on by older kids or some of the Puerto Rican or black kids from the surrounding neighborhoods. I loved baseball, but I loved not getting wedgies and not having to run from a large group of Puerto Rican kids who wanted my glove even more.

Instead, as city kids, we improvised, playing various baseball-type games that were easier and more accessible to us. There were five variations:

- Wiffle ball: This was Played in a schoolyard with as little as two players with your standard Wiffle ball and yellow bat. There were no bases. One strike and you were out, three outs per inning. Anything over the fence was a home run; anything that got past the pitcher was a single; anything successfully fielded (even a grounder) was an out. Play until you have to go home or your arms fall off. Keep score dutifully. Most likely fight with opponent about the score.

- Stickball: Similar to Wiffle ball with three differences: 1) played with stick and rubber ball; 2) a strike zone is drawn behind the hitter against the wall of the school, and the hitter now has three strikes per out; 3) fighting over scoring more intense than in Wiffle ball, due to the more fast-paced nature of the game.

- Halfball: Same as stickball, but played with a tennis ball cut in half. My least favorite baseball-derived game. (Why would anyone cut a perfectly good tennis ball in half?)

- Streetball: Played with full teams in the street/schoolyard, with bases drawn in chalk on the asphalt/cement. Like real baseball, except with tennis ball and loaded Wiffle-ball bat (a Wiffle-ball bat cut open, stuffed with newspapers, and taped up). Also unlike real baseball in that someone’s mildly retarded younger brother will be required to play and a fight will usually break out between the older nonretarded brother and the younger somewhat-retarded brother. Hilarity will ensue, Sunny Delight will be consumed, purple stuff will be eschewed.

- Killball: Like streetball, but a mix of 90 percent baseball and 10 percent dodgeball. A hitter can be called out if the fielder catches his ball, throws it at him, and hits him with it when he is not on base. It was with the birth of this game that many of us realized that our testicles were sensitive things to be respected, rather than decorations dangling below our penises.

I spent the early part of my youth playing these games religiously. By the time an opportunity to play in Little League presented itself, I felt like I was ready to take that next step.

Yet I don’t want to give the impression that I was just some kid playing the game because he had nothing else to do or because playing Little League is just what you’re supposed to do as a kid. I loved baseball—a lot—not just to play, but to watch and enjoy as well. Every day I’d pore over the sports section of the

Daily News,

analyzing the box scores, noting how many hits Mike Schmidt had, whether or not Juan Samuel had stolen a base, or if Steve Bedrosian had picked up the save. I collected baseball cards with a frightening obsession/compulsion that would meet its equal later in my life only when a) I discovered masturbating; b) I discovered getting drunk; and c) I discovered sex.

*

Collecting baseball cards was not just a hobby, it was a lifestyle. My mom inadvertently ruined the second half of 1988 for me when she got me some lame-ass OshKosh B’gosh overalls for my birthday instead of the Donruss-brand Jose Canseco rookie card that I so desperately wanted.

**

I spent hours lusting after prized cards in Lou’s Cards & Comics on Broad Street and whole afternoons and evenings in my room studying the statistics on the backs of the cards. If you had asked me how many hits Wade Boggs had in 1983, how many home runs Dale Murphy hit in 1985, or how many strikeouts Doc Gooden had in his rookie year, I could tell you instantly.

*

If I had put half as much effort into schoolwork as I did studying these cards, I would have graduated from grade school in four years and would now probably be a Ph.D. touring the country lecturing on the reproductive habits of the cnidarians of the South Pacific. Instead it took me eight whole years to graduate and now I couldn’t tell you which president is on the twenty-dollar bill.

**

Stupid baseball obsession.

I wasn’t just a stat nerd; I watched a lot of games, too. Baseball became my first love in large part because it was (and still is) the most accessible of sports. First and foremost, there are 162 freaking games, double that of hockey and basketball and ten times that of football, allowing for plenty of time to get familiar with the sport. Not only that, the bulk of baseball is played during the summer, when kids all over the country are off from school and driving their parents crazy by telling them things like “Dad, it’s a long story, but the air conditioner caught on fire” and “Mom, I’m not sure how it happened, but Dennis is gone—can you make me another little brother?” as soon as they get home from work. So when not being tremendous pains in the asses, my friends and I enjoyed nothing more than sitting in front of the television watching the Philadelphia Phillies play some of the worst baseball in the major leagues. And we had ample time to do so.

My friends and I were also lucky because we lived just over a mile away from Veterans Stadium, the home of the Phillies. A general admission ticket to a Phillies game was only four bucks and you couldn’t get much more adventurous than you and your friends trekking all the way up the Vet to take in a game—without adults. My buddies and I would head to an afternoon game, buy our cheap tickets, and then spend the first third of the game trying to move closer to the field and sneak into better seats. Fortunately, this was easy to do, as, like I said, the Phils weren’t exactly packing them in at the time with their high-quality play. Then we’d sit and watch, taking it all in, basking in the glow of America’s great pastime. This was the ultimate for us, sitting in the stands, the sun, the heat making our hair matted with sweat under our cheap mesh Phillies hats. It was such a grown-up thing to do—“We’re going to the Vet to catch a ball game”—but also so easy. And because baseball imbued us with such a great sense of responsibility at such a young age, we repaid the sport with our fierce loyalty.

Loyalty or not, the Phillies stunk. The roster of players that passed through the teams during this time was laughable, but there was one Phillie who stood above all others. A man whose push-broom mustache teemed with virility and strength. A man whose presence in a powder-blue Phillies uniform would inspire a generation of young kids to try to knock one out of the park. His name was Michael Jack Schmidt. And he was my idol.

Mike Schmidt’s career was winding down by the time I began to get into baseball (though I did get to appreciate some of his good years toward the end there, like his MVP season in 1986). But Schmidt was the first athlete that I was aware of who transcended his sport. He was not only the best player in baseball in the 1980s, he had so woven himself into the fabric of Philadelphia, a city to which he had helped bring a championship, that each time he came to the plate it was not an at-bat but actually an

experience

that garnered a combination of respect, awe, and gratitude from the fans. And then, if he struck out, the fans would boo the shit out of him. Hell, even if he didn’t strike out, we’d

still

boo the shit out of him. We might have loved him, but hey, we were still Philly fans. Remember—we’re the ones who threw snowballs at Santa Claus (because he was drunk), batteries at J. D. Drew (because he was a prick who refused to sign with the team when drafted by them), and applauded Michael Irvin of the Dallas Cowboys when he lay on the turf of the Vet with a potentially serious spinal injury (because, well, he’s Michael Irvin).

Because of old number 20, the final piece of the puzzle for Little League was set: I would play third base, just like Schmidty. I would also grow a mustache like him, but that might take some time. For now, I had the experience, the love, the knowledge, and the plan. But every superstar has to start somewhere, so in the spring of 1987 I hopped into my dad’s truck and we went the orientation meeting for Sabres Youth League Baseball. My destiny awaited. My time had come. Play ball.

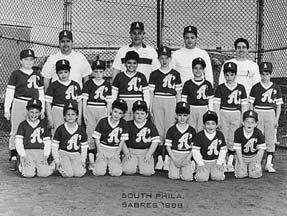

The author (standing, far left) and his teammates prepare for another grueling season of McDonald’s and talking about masturbating.

It started fortuitously enough. After signing up, I was assigned to a team, the A’s, and given a uniform just like the green and yellow one that the Oakland A’s had, so I looked the part of a big-league player. Not only that, I was able to procure the number 20, the same number worn by Mike Schmidt himself. I overlooked the fact that it was the only number left in my size and attributed this coincidence to fate. The gods were smiling upon me. This was going to be great.

[

dramatic pause with DUM-DUM-DUMMM music

]

Well, at least that’s what I thought.

I ended up playing two seasons in Little League. If I had a baseball card, my stats could be broken down as follows:

- Games played: 25 (out of a possible 26)

- Team record with me: 0-25

- Team record without me: 1-0

- Number of at-bats: 75

- Hits: 1

- Number of times my bat made contact with a pitch: 3

- Number of times the contact my bat made with a pitch was accidental: 3

- Doubles: 0

- Triples: 0

- Home runs: 0

- Walks: 8

- Number of times hit by pitch: 6

- Number of times I cried after being hit by a pitch: 11

- Number of times I cried for other reasons (no more barbecue potato chips, my batting helmet is too small, I’m missing the Balki show, etc.): 22

- Pepsis consumed: 148

- Number of times masturbation discussed on the bench: 512

- Number of times those discussing masturbation had actually masturbated: 0.5 (Once our second baseman admitted that he rubbed his sister’s friend’s bra on his bird, so we gave him half credit. The rest of us said that we had masturbated, but of course we were lying.)