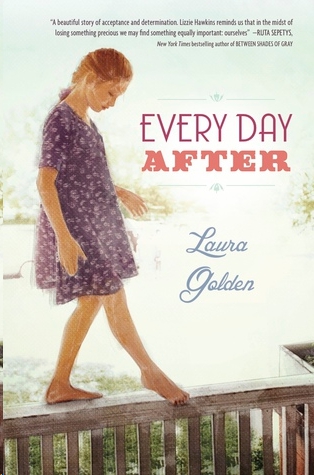

Every Day After

Authors: Laura Golden

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2013 by Laura Golden

Jacket art copyright © 2013 by Masterfile

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Zondervan for permission to reprint the poem “Wits’ End Corner” by Antoinette Wilson from

Streams in the Desert: 366 Daily Devotional Readings

by L. B. Cowman, copyright © 1996, 1997 by Zondervan. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Zondervan.

Visit us on the Web!

randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Golden, Laura.

Every day after / Laura Golden. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: “A young girl fights to keep her mama out of the mental ward, her home away from the bank, and herself out of the orphanage after her father abandons her and her mother in depression era Alabama”—Provided by publisher.

eISBN: 978-0-307-98312-1

[1. Self-reliance—Fiction. 2. Abandoned children—Fiction.

3. Family problems—Fiction. 4. Depressions—1929—Fiction.

5. Alabama—History—1819–1950—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.G56474Ev 2013

[Fic]—dc23

2012015770

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

For Michael, who told me to write a

novel in the first place

And in memory of Jake and Nelda Perry—

one part Ben, one part Lizzie,

both deeply missed

Contents

One: A Gem Is Not Polished Without Rubbing, nor a Man Perfected Without Trials

Two: After Honour and State Follow Envy and Hate

Three: He Who Would Gather Roses Must Not Fear Thorns

Four: Luck Follows the Hopeful, Ill Luck the Fearful

Five: Heaven Is at the Feet of Mothers

Six: When I Did Well, I Heard It Never; When I Did Ill, I Heard It Ever

Seven: Life Is Like the Moon: Now Full, Now Dark

Eight: If Not for Hope, the Heart Would Break

Nine: Nice Doesn’t Always Mean Good

Ten: A Loyal Heart May Be Landed Under Traitor’s Bridge

Eleven: Pride Goeth Before Destruction and a Haughty Spirit Before a Fall

Twelve: Banks Lend Umbrellas When the Sun Is Shining and Ask for Them Back When It Starts to Rain

Thirteen: Hard Work Means Prosperity; Only a Fool Idles Away His Time

Fourteen: The Sting of a Reproach Is the Truth of It

Fifteen: The Days Are Prolonged and Every Vision Faileth

Sixteen: By Land or Water, the Wind Is Ever in My Face

Seventeen: He Who Makes a Mouse of Himself Will Be Eaten by the Cats

Eighteen: ’Tis Perseverance That Prevails

Nineteen: A True Friend Is Known in the Day of Adversity

Twenty: The Greatest Conqueror Is He Who Conquers Himself

Twenty-one: A Friend Is Not Known Till He Is Lost

Twenty-two: Misfortune Is a Good Teacher

One

A Gem Is Not Polished Without Rubbing, nor a Man Perfected Without Trials

I learned a lot from my daddy, but the number one most important thing is this: never, ever, under any circumstances, let something get the best of you. To do this, you gotta work with what you got, play the cards you been dealt, turn lemons into lemonade. Too bad he wasn’t around to see me doing just that, because one thing’s for sure: when it rains in the South, it pours.

The late-April thunderstorm that had occurred overnight made my walk to school particularly interesting. Plodding a mile through red mud in shoes a size too small with four holes too many ain’t the easiest thing to try. With the depression on, I wasn’t the only one with this problem, but I might’ve been the only one who knew how to make the best of it. I’d turn lemons into lemonade by using Mother Nature’s mess as an excuse not to worry about Daddy. Or Mama. I’d only worry about the mud, and how to get more of it. Instead of trying to keep it off

my shoes, I’d see how much I could pack onto them. At least the cardboard cutouts inside would keep the bottoms of my socks from staining.

About every fifteen yards the mud would reach its highest clumping point and fall off. Maybe lighter steps would help it last longer.

A gruff voice broke my concentration. “Hey, Lizzie, wait up!”

“I was starting to wonder what’d happened to you,” I said without turning around so I wouldn’t break my mud.

I’d have known that voice anywhere. Ben’s voice. I’d known him practically since birth. We were born within days of each other, and our mothers had once been best friends. Ben was my one true friend. I learned that over three years back, at the tail end of third grade. Myra Robinson had dared me to go up to crazy old Mr. Reed’s and knock on his door. And that wasn’t the worst of it. She expected me to talk to him. Me. Talk to a man older than the hills who probably hadn’t said a hundred words since I’d been born. I figured if he’d felt like talking, he’d have talked, and I didn’t care to be the one forcing him to do it.

I might not have been so nervous if Mr. Reed had been like any regular man and gone into town a good bit, or if he’d have darkened the doors of the Bittersweet Baptist Church at least on Easter Sundays. But Mr. Reed wasn’t any regular man. He never went to church, and he headed into town exactly twice a month—on the first and the

fifteenth from one p.m. till three p.m. But Myra had to go and dare me at precisely 3:17 p.m. on the eighth of March in the year 1929. Dang. He’d be home.

Ben had put his hand on my shoulder. “I’ll go with you, Lizzie. I ain’t scared.”

Myra, along with about ten other nosy bystanders, trailed us into town. We turned off Main onto Oak Street, then onto Mr. Reed’s rutted dirt drive, which led directly to his house up on the hill behind town. I didn’t know about Ben, but I was as nervous as a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs. We tiptoed over the junk in the front yard—cracked mirrors, broken chairs, rusty pitchforks and hoes—and onto the sagging front porch. Daddy said Mr. Reed had lived alone for close to fifty years. I knew two things for certain: the house hadn’t had a fresh coat of paint in all that time, and anything that broke got thrown out in the yard, not in the trash. Ben and I faced the splintered wooden door. He looked at me and nodded. I knocked. Slowly, the door creaked open, and there stood Mr. Reed, all leathery and wrinkled and thin as a bone.

He looked at us like

we

were the crazy ones. “What you kids need?” he asked. His voice was as rough as sandpaper. He put a cigarette to his mouth and took a long suck off it. Ben and I stood there blinking. Neither one of us knew what to say. We didn’t need anything, except to get the heck out of there.

Ben was the one to find words. “Sorry to trouble ya, Mr. Reed. I don’t reckon we need much of anything. We’ll just be goin’.”

Mr. Reed nodded and closed the door, and Ben and I took off like our tails were on fire.

“Did you do it?” Myra asked at the bottom of the hill. “What’d he say?”

“Yeah, we did it,” I said. “And if you want to know, you go ask him yourself.”

All the bystanders went abuzz, and Ben and I walked away. I could still hear my heart pounding in my ears. I’d never been gladder to have Ben by my side than I was that day. We’d been extra close ever since.

Now Ben walked beside me, staring down at my mud-covered shoes. “Sorry I’m late. Had to help Ma make the beds and clean the kitchen on top of my regular chores. What in the heck are you doin’?”

“Is she sick?” I asked, ignoring his question.

“Naw, she ain’t sick. She’s real busy tryin’ to get a wedding quilt finished for Mrs. Martin’s daughter. Mrs. Martin told Ma she needed it done by this evenin’, nearly a week sooner than it was supposed to be due. Said she’d misfigured the time it’d take the postal service to get it out west to her daughter. Put Ma in a real hard spot.”

I shook my head and sank into some soft mud. The clumps on my shoes grew. “I guess all those boarders living with her put her mind in a tizzy. The last few times I’ve gone to pick up some mending, she’s either been in a

big hurry or snappy. Charlie told me he and John have to share their room with two other boys no more than five years old. If there was that many people crammed into my house, I’d probably have trouble thinking straight too.”

Ben pulled a small rock from his pocket and placed it in his slingshot. Huge wads of mud covered my shoes. The weight nearly pulled them right off my feet. It was rather relaxing. Not up there with fishing or anything, but relaxing. Ben snapped his slingshot, and the rock smacked a pine.

“Why don’t you teach me how to do that? Then we could have contests.” I glanced over at him. “Contests I could win.”

Ben pretended not to hear me. “I can’t much blame Mrs. Martin either. A bunch of strangers stuffed in my house is the last thing I’d want.”