Every Contact Leaves A Trace

Read Every Contact Leaves A Trace Online

Authors: Elanor Dymott

Contents

Prologue: London, Friday 21 December 2007: Early Morning

Part I: London, Friday 30 November 2007: Late Evening

Part II: London, Friday 21 December 2007: Early Morning

Epilogue: New York, Saturday 21 June 2008: 4 A.M.

About the Book

‘If you were to ask me to tell you about my wife, I would have to warn you at the outset that I don’t know a great deal about her. Or at least, not as much as I thought I did…’

Alex is a solitary lawyer who has finally found love in the form of his beautiful and vivacious wife, Rachel. When Rachel is brutally murdered one Midsummer Night by the lake in the grounds of their alma mater, Worcester College, Oxford, all of his happiness is shattered. He returns to a snowbound Oxford that winter and, through the shroud of his shock and grief, attempts to piece together the story behind her death.

With Rachel’s former tutor and trusted mentor as his guide, Alex begins to uncover disturbing secrets and constantly shifting versions of the truth. As he delves deeper into the mystery, he is forced to confront the horrifying fact that his entire understanding of the past will be forever altered by the telling of this tale.

Part love story, part murder mystery, this is an extraordinary debut from a powerful new voice in fiction, guaranteed to make your heart beat faster and faster.

About the Author

Elanor Dymott was born in Chingola, Zambia, in 1973. She was educated in the USA and England and also spent parts of her childhood in South East Asia. Having read English at Oxford she qualified as a lawyer before becoming a law reporter. Her short fiction has been published in

Stand

,

The Warwick Review

and

Algebra

.

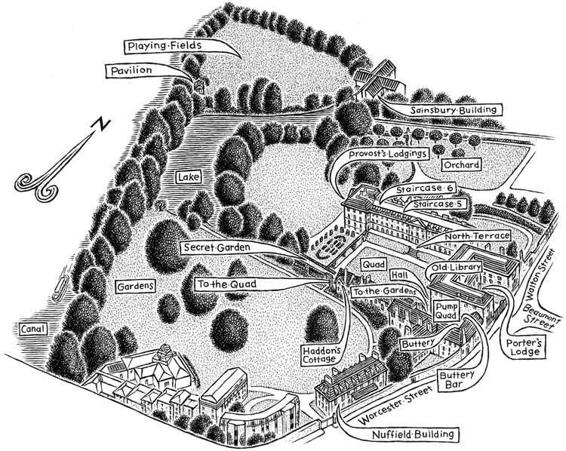

A Map of Worcester College

VERY

C

ONTACT

L

EAVES A

T

RACE

Elanor Dymott

Have you seen the white lily grow

Before rude hands have touched it?

Have you marked the fall of the snow

Before the soil hath smutched it?

Have you felt the wool of beaver

,

Or swan’s down ever?

Or have smelt o’ the bud o’ the brier

,

Or the nard in the fire?

Or have tasted the bag of the bee?

O so white, O so soft, O so sweet is she!

Ben Jonson,

The Devil is an Ass

Il est impossible au malfaiteur d’agir, et surtout d’agir avec l’intensité que suppose l’action criminelle sans laisser des traces de son passage. Ces traces sont extrêmement diverses: il faut avoir présent à l’esprit que, dans chaque affaire, on peut en trouver d’une sorte différente

.

Edmond Locard,

Manuel de Technique Policière

BENVOLIO

I do but keep the peace. Put up thy sword

,

Or manage it to part these men with me

.

William Shakespeare,

The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet

Act 1, Scene i

A Note for the Reader

At the very end of December 2007 Alex Petersen met Ian Schoenherr, illustrator and cartographer. The two men became friends, and Alex began to tell Ian a version of the story you are about to read. In the months that followed, Ian drew several maps for his friend of the places he had spoken of, thus giving his story back to him having shaped it for him anew. One of those maps was of Worcester College, Oxford, as Alex had described it in the course of telling his tale. Readers who wish to consult the map will find it

here

.

P

ROLOGUE

London, Friday 21 December 2007

Early Morning

If you were to ask me to tell you about my wife, I would have to warn you at the outset that I don’t know a great deal about her.

Or at least, not as much as I thought I did.

And I would go on to say that reaching such a conclusion, if I can call it that, has been, for me, a process of discovery: I went into a dark room with my camera for a time, and I came out with a photograph of a woman I had never seen before.

It is perhaps because of these fluctuating states of knowing and un-knowing that, when I am asked that sort of a question, I find it a little difficult to decide where to start.

She died six months ago, almost to the hour. On Midsummer Night in Oxford, underneath a great and spreading plane that grows in the gardens of Worcester College as you walk down to the lake, the bridge to the Provost’s garden somewhere on your right hand side and a new moon rising. That was where I found her body. It is, as a place to begin, as good as any other. Or, I suppose, as a place to die. As a place to have your head stoven in by someone bringing a stone, lifted from the lake and still covered in weed and scum, down onto your skull six or seven times as you crouch to the grass, your face getting closer to it with each blow until at the fourth you give up and sink into it, smelling memories there, and the moistness of the evening, and wishing things had turned out differently.

I do not think she would have minded being brought this close to the ground when she died. Had the choice been left to her she would doubtless have selected some other method. But the grass itself, the fact that it was damp and that it stained her dress in the

way

that it did; that would not have troubled her. She was the sort of person who would sit down on a lawn whatever she was wearing, or kneel on damp earth if she wanted to. And after all, that was exactly what she did the night I met her at Richard’s wedding, the night before the morning she agreed to become my wife.

P

ART I

London, Friday 30 November 2007

Late Evening

1

IT WOULD NOT

be inaccurate of me to describe Richard as my closest friend, although I doubt it would occur to him to refer to me in quite the same way. Oldest friend then, rather than closest, and I can say that with confidence since our first meeting took place within hours of our arriving at Oxford, over a tea given by our tutor. It is those initial meetings that stick in the mind. The hands I shook in the first few days of the Michaelmas term are the ones I can almost feel against my palm still. If I try to, that is; if I think back.

‘The study of law,’ Charles Haddon said to us as we stood in his drawing room, ‘will only disappoint those of you who approach it with anything other than the expectation that, in order to succeed, you will have to work phenomenally hard. There will be one or two of you who think, erroneously, that the really challenging work is behind you. That the small modicum of success you have garnered in your little clutch of A’s at A level was what mattered. There may even be some among your number who are under the illusion that by having won your place here, you have won also the right to enjoy yourselves. Let me assure you that such an assumption would be the gravest of errors, and one not without consequences. That is all I have to say, for now. There are scones behind you, and tea in the urn by the window.’

If this speech made me want to melt into the curtains and remain there, it seemed to have the opposite effect on Richard, who sprang forward and started a debate with Haddon about an article of his that he’d read in

The Times

. We were to be tutorial partners for the next three years, Richard and I, and this pattern would continue throughout that time without either of us much minding: me

observing

almost without comment while Richard and Haddon battled things out between them. We did as well as one another in the end, each of us sticking to Haddon’s advice. We breakfasted together in Hall every morning before going to lectures and having lunch in the faculty. Then we came back to College and stayed at our desks in the Old Library until the supper bell rang, breaking only for tea in the Buttery and a stroll around the lake, and of course for our Friday afternoon sessions with Haddon.