Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 (30 page)

Read Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #Military History, #Retail, #European History, #Eurasian History, #Maritime History

It was an extraordinary diplomatic coup by Pius; he appeared to have succeeded where fifteen of his predecessors had failed. To forge a united front to push back the infidel had long been one of the most ardent papal objectives. Pius, by sheer willpower, persistence, and money had achieved what many had believed was impossible, but despite the fine words in which the agreement was couched, many seasoned observers remained skeptical. In January, Philip had predicted that “as the League is now, I do not believe it will do or achieve any good at all.” As if to justify these remarks, the ink was hardly dry before Spain tried to renege on the terms. Pius had to whip the Spanish back into line by threatening to withdraw the crusading subsidies again. Many others remained equally unconvinced. “It will look very fine on paper…but we shall never see any results from it,” wrote the French cardinal de Rambouillet during the negotiations. He saw nothing later to change his mind, and in Istanbul they were hopeful too, after the failed expedition of 1570, that the whole thing would collapse of its own accord.

The fact that the league held together for any time at all was largely the conjunction of two remarkable circumstances. The first was the choice of leader of the joint Christian battle force, Don Juan of Austria, Philip’s half brother, the illegitimate son of Philip’s father, Charles V. The second was the violent and extraordinary denouement to the siege of Famagusta that was unfolding as the delegates signed and the crowds cheered.

THE SPRING SAILING

had brought Lala Mustapha fresh men; Cyprus was so close to the Ottoman coast that no matter how many men died, replenishment was an easy matter. Word of the rich pickings at Nicosia had got about, and the pasha proclaimed, perhaps unwisely, that the booty at Famagusta would be better still. Adventurers and irregulars flocked to the cause. By April, Lala Mustapha had a vast army, somewhere in the region of one hundred thousand men. The Ottomans boasted that the sultan had sent so many to the siege that if each one threw a shoe into the ditch, they would fill it up. Crucially, a large number of these were miners, armed only with picks and shovels. Within the walls, there were four thousand Venetian infantry and the same number of Greeks.

By mid-April, Lala Mustapha was ready to press forward in earnest. Bragadin counted his finite food stocks and decided that there was no alternative but to expel the noncombatants. Five thousand old men, women, and children were given food for one day and marched out of a sally port. Any ruthless besieging general might now be expected to take advantage. Julius Caesar let the women and children die of starvation, hemmed in between the Roman legionnaires and Vercingetorix’s fort in 52

B.C.;

Barbarossa forced them back to the walls of Corfu in 1537. The mercurial Lala Mustapha did neither. He let them return to their villages. It was both compassionate and astute, a guarantee of goodwill toward the Greek population.

Bragadin was determined to emulate the defense of Malta, but there were crucial differences—not only was Famagusta fourteen hundred miles from any help, but the geology was different too. Birgu and Senglea had been built on solid rock; tunneling had required superhuman effort. Famagusta was constructed on sand—easy to mine, even if it required constant propping. In late April, Lala Mustapha’s huge labor force started to shovel their way toward the city. The Christians jeered at the Turks for waging war like peasants, with picks and shovels, but the strategy was terribly effective. A vast network of trenches zigzagged toward the moat, so deep that mounted men could ride along them with only the tips of their lances showing, so extensive that the observers declared the whole army could be accommodated within them. Earth parapets were thrown up that concealed all but the tops of the Ottoman tents, and earth forts constructed fifty feet wide and bulwarked with oak beams and sacks of cotton. If these were destroyed by gunfire, they were quickly rebuilt. When the platforms overtopped the walls, they were mounted with heavy cannon.

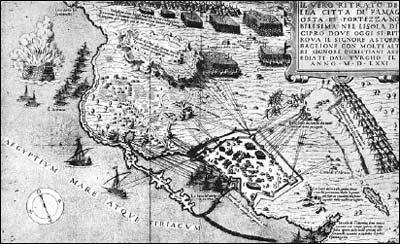

Famagusta under siege

The defenders fought with the confidence of the Knights of Saint John for the honor of their little republic. Baglione conducted sorties and ambushes, picked off miners, threw gunpowder into their trenches, hid planks in the sand studded with poisoned nails, knocked out gun emplacements, and killed alarming numbers of men. The fortitude of the defense astonished and worried the Ottoman high command. Men wrote home to Istanbul that Famagusta was defended by giants. When Lala Mustapha sent a message to Bragadin on May 25 with yet another request for surrender, he was met with shouts of “Long live St Mark.” One of these parleys was rebuffed with a hotter response. The Venetians lived in eager hope of relief, and Bragadin invited the messenger to tell his master that when the Venetian fleet came, “I shall make you walk before my horse and clear away on your back the earth you have filled our ditch with.” These were not wise words.

Eventually the weight of numbers started to tell. In early May, as the Holy League prepared to append their signatures in Rome, the Ottoman cannon started a heavy bombardment. Day after day they poured shot into the houses to break the citizens’ morale, and against the walls to batter them down. Despite heroic repair work, Lala Mustapha’s men inexorably degraded the fortifications; tunneling allowed them to plant mines and blast the front off the ravelins and bastions. On June 21 the Ottomans opened a definitive breach and delivered the first of six furious assaults that gradually whittled away the defense. Supplies of food and gunpowder began to dwindle. “The wine is finished,” wrote the Venetian engineer Nestor Martinengo, “and neither fresh nor salted meat nor cheese could be found, except at a price beyond all limits. We ate horses, asses, cats, for there was nothing else to eat but bread and beans, nothing to drink but vinegar with water and this gave out.” On July 19, the bishop of Lemessos, a talismanic figure for the people, was killed at his table by an arquebus. The Greek citizens had supported their Venetian masters faithfully; now they had had enough. Mindful of the end of Nicosia, they petitioned Bragadin for surrender. After an emotional mass in the cathedral, Bragadin begged them for fifteen more days. They assented, but the Ottomans too knew the end was near. On July 23, Lala Mustapha, increasingly frustrated by what he regarded as pointless resistance, shot a blunt message over the wall to Baglione, yet again repeating Suleiman’s formula at Rhodes:

I, Mustapha Pasha, want you milord general, Astorre, to understand that you must yield to me for your own good, because I know that you have no means of survival, neither gunpowder nor even the men to carry on your defence. If you surrender the city with good grace, you will all be spared with your possessions, and we shall send you into the land of the Christians. Otherwise we shall seize the city with our great sword, and we shall not leave a single one of you alive! Mark you well.

CHAPTER

18

Christ’s General

May to August 1571

W

HILE LALA MUSTAPHA WAS CLOSING

in on Famagusta, the Holy League’s naval preparations lumbered into action. In all the ports of Spain and Italy—Barcelona, Genoa, Naples, Messina—men, materials, and ships were being laboriously gathered. The Western Mediterranean was a hubbub of disorganized activity: badly coordinated, unprepared—and late. The Venetian ambassador in Spain watched the proceedings in impotent fury. “I see that, where naval warfare is concerned, every tiny detail takes up the longest time and prevents voyages, because not having oars or sails ready, or having sufficient quantities of ovens to bake biscuits, or the lack of fourteen trees for masts, on many occasions hold up on end the progress of the fleet.” It all contrasted so badly with the central coordination of the Ottoman military machine: its plans were laid far in advance, their execution ensured by unbreakable imperial edict. The governor of Karaman had lost his post for being ten days late in collecting men for the Cyprus campaign the previous year. The Ottomans had a battle plan to meet the Christian threat, and they followed it rigorously in the spring of 1571. The admiral, Ali Pasha, had sailed to Cyprus in March; another fleet under the second vizier, Pertev Pasha, left Istanbul in early May; the third vizier, Ahmet Pasha, marched the land army west in late April to threaten Venice’s Adriatic coast; Uluch Ali sailed east from Tripoli. The campaign was to be much more extensive than the conquest of Cyprus. It was intended to carry the fight into the heart of the Adriatic, even to capture Venice or beyond: “The domination of the Turks must extend as far as Rome,” Sokollu rhetorically informed the Venetians. By late May, Ali and Pertev, judging the siege of Famagusta to be nearly over, combined their fleets and started to ravage Venetian Crete.

The Venetians were desperate for something to happen. Their galley fleet was at Corfu by late April, under the new commander Sebastiano Venier. After the shameful display of the previous year under Zane, the Venetians had now entrusted their enterprise to a formidable man. Venier, already seventy-five years old, with the looks of a bad-tempered lion from some Venetian plinth, was a redoubtable patriot; though no sailor, he was a resolute man of action—impetuous, decisive, and possessed of an explosive temper. He received news of the plight of Cyprus with growing impatience and tried unsuccessfully to persuade his officers that they should strike out for Famagusta on their own, without waiting for the prevaricating Spaniards. It was judged to be too risky; the fleet was still understrength. There was nothing to do but wait. Slowly the allies started to converge on Messina, on the north coast of Sicily, the agreed rendezvous for the operation. Marc-’Antonio Colonna was again appointed to command the papal galleys at the insistence of Pius V, despite the previous year’s debacle. By June, Colonna was at Naples. Now all they could do was await the arrival of the Spanish and the leader of the whole expedition.

It fell to Philip to choose this commander; his first nominee had been the ever cautious Gian’Andrea Doria. This was immediately ruled out by the pope—he personally blamed Doria for the failure of 1570, and the Venetians detested him. Philip’s second suggestion was his young half brother, Don Juan of Austria. It was to prove an extraordinary choice.

Don Juan, twenty-two years old, good-looking, dashing, intelligent, chivalrous, and daring, driven by an unquenchable appetite for glory, was the antithesis of his half brother, the prudent Philip. He had already proved himself as a military commander during the Morisco revolt, but not without taking what Philip considered unacceptable risks. When Don Juan had placed himself in the front line and been hit on the helmet by an arquebus bullet, Philip was outraged. “You must keep yourself, and I must keep you, for greater things,” he wrote reprovingly. For Philip, Juan represented the only possible dynastic successor in 1571; he was determined not to risk him in battle. To keep him in check, and to ensure astute maritime advice—for Don Juan had no sea experience—he closely shackled his authority with a team of seasoned advisers that included Gian’Andrea Doria, Luis de Requesens, and the marquis of Santa Cruz, Álvaro de Bazán, an experienced seaman. Though Bazán was by nature more likely to favor aggressive action, Philip felt that any likelihood of actual battle had been removed by his insistence that no engagement with the enemy should be undertaken without the unanimous agreement of these three men. He thought that he could count on Doria to deliver a veto.

Don Juan

These restraints irked the young prince. His appetite for glory had been stoked by the circumstances of his birth. His illegitimacy made his position within the royal household anomalous, and Philip went out of his way to deliver casual slights to the over-popular young man. He refused Don Juan the title of Highness; he was merely to be called Excellency. In an age of touchy protocol these niceties mattered. He might be Philip’s default successor, but in the interim the king was not going to confirm his royal status. Worse still, Philip undercut Don Juan’s position as commander by communicating the order to seek the consent of his advisers to Don Juan’s own subordinates. There is a tone of deep hurt wrapped around Don Juan’s elaborate written replies to his half brother: “With due humility and respect, I would venture to say that it would be to me an infinite favour and boon if Your Majesty would be pleased to communicate with me directly with your own mouth…[rather than] reducing me to an equality with many others of your servants, a thing certainly in my conscience not deserved.” Don Juan longed for glory, confirmation, ultimately a crown of his own. Shadowed by graybeards who had been tasked with preventing him from achieving anything at all, he was a man with something to prove. As he prepared to depart from Madrid in early June, the papal delegate in Spain understood, with approval, that Don Juan was eager to throw off these shackles. “He is a prince so desirous of glory that if the opportunity arises he will not be restrained by the council that is to advise him and will not look so much to save galleys as to gather glory and honour.”

TWELVE HUNDRED MILES AWAY,

the man who would oppose him as admiral of the Ottoman fleet was preparing to raid Crete. At first glance Muezzinzade Ali Pasha—Ali, “the son of the muezzin”—seemed a creature from a different world. Where Don Juan was born half into the royalty of Europe, Ali was the son of the poor; his father called people to prayers in the old Ottoman capital at Edirne, one hundred forty miles west of Istanbul. Through the meritocratic system of Ottoman preferment, Ali had risen to the position of fourth vizier, and now to the exalted position of

kapudan pasha

—admiral of the sultan’s fleet—the post once held by the great Hayrettin Barbarossa. Ali was a man of whom people spoke well: “brave and generous, of natural nobility, a lover of knowledge and the arts; he spoke well, he was a religious and clean living man.” Yet like Don Juan, he was also something of an outsider. It had become the custom for the sultan’s ruling elite to be drawn from the ranks of converted Christians, usually captured as children—men who owed everything to the sultan and were brought up in his court. Sokollu was a Bosnian; Piyale had been taken as a child from the battlefields of Hungary. Ali was unusual in being an ethnic Turk; “coming from and growing up in the provinces, he was considered an outsider in the eyes of the important people of the sultan’s palace, and this was considered a fault.” He was not part of the ruling elite. Like Don Juan, he was a man with something to prove; he was ambitious for success in his sovereign’s eyes. He too was brave to the point of recklessness, and he was driven by a matching code of honor: to draw back would be cowardly.

Crucially, neither man possessed much experience of sea warfare. It was not coincidental that the contest for the Mediterranean had been marked by a singular absence of large-scale sea battles; even Preveza had been little more than a glancing blow. The men who had maneuvered their fragile galley fleets so skillfully—Hayrettin Barbarossa, Turgut, Uluch Ali, Andrea Doria and his great-nephew Gian’Andrea, Piyale, and Don Garcia—had been deeply cautious. It was with good reason. They understood the conditions of the sea and its fickleness; a sudden stopping of the wind or its increase, an unwise maneuver close to shore, a minuscule loss of tactical advantage, could cause havoc. Long experience had taught that the margin between victory and catastrophic defeat was paper-thin; these men weighed the risks accordingly. The two admirals now assembling the largest galley fleets ever seen had none of this experience—they were eager to seek out the enemy directly and fight. Ali carried explicit orders to this effect. It was a combustible set of circumstances.

MANY OF THE SEASONED OBSERVERS

on the Christian side doubted that the whole laborious gathering of ships, men, and materials could amount to anything, especially if led by the Spanish. Don Juan’s progress toward Italy was tortuous. He left Madrid on June 6. It took him twelve days to reach Barcelona, then he waited a month for everything to be readied. “The original sin of our court is never to get a thing done with dispatch and on time,” wrote Luis de Requesens to his brother from Barcelona, watching and sighing. Eventually, on July 20, Don Juan stepped aboard his sumptuously ornate galley, the

Real,

and departed to cheering crowds and gunfire. Every step of the way he was slowed down by rapturous receptions, huge crowds, illuminations, fireworks, festivities, monastery visits, and church services. Everyone wanted to catch a glimpse of the charismatic young prince, to detain and honor him. It was less a march to battle, more a royal progress, touched by explosive expressions of religious and crusading zeal, as if the ports along the route—Nice, Genoa, Civitavecchia, Naples, and Messina—were stations of the cross.

At Genoa, the Dorias entertained Don Juan as they had entertained his father, Charles V, with masked balls. “Everybody was surprised and delighted by the spirit and grace of the dancing of Don Juan,” it was reported, like a court circular. Not to be outdone, Naples laid on a brilliant reception for the young man. News of his progress swelled across Southern Europe, each landfall amplifying the sense of expectation and crusading zeal. A breathless communiqué to Rome captured the spectacular arrival of Christ’s general there on August 9: “Today at 23 hours Don Juan of Austria made his entrance to the enormous delight of the people. Cardinal Granvelle went to receive him at the harbour mole, and gave him his right hand. The said lord is fair-skinned with blond hair, a sparse beard, good-looking and of medium height. He was mounted on a very fine grey horse in handsome battle dress and he had a very good number of pages and footmen dressed in yellow velvet with deep blue fringes.” The next day he drove through cheering crowds from the port to the palace in the cardinal’s coach in a spectacular outfit of gold and crimson, followed by a long procession of nobles. At each harbor, the ships boarded detachments of Spanish and Italian troops, all King Philip’s men.

Don Juan receives the banner of the League

The pope had sent Cardinal Granvelle to Naples to consecrate the young commander in magnificent style. Granvelle was something of an ironic choice; as one of Philip’s representatives at the league negotiations, no one had shown more ill will to the proceedings with his interminable quibbling and foot-dragging. At one point the exasperated Pius had forcibly driven him from the room. Now, at an elaborate service in the church of Saint Clara on August 14, Granvelle conferred on Don Juan the badges of office as leader of the Holy League. Kneeling before the high altar, Don Juan received his general’s staff, and an enormous twenty-foot-high blue banner—the color of heaven—a gift of the pope, bearing the elaborately wrought image of the crucified Christ and the linked arms of the league participants. “Take, fortunate prince,” intoned Granvelle in a sonorous voice, “take these symbols of the true faith, and may they give thee a glorious victory over our impious enemy, and by thy hand may his pride be laid low.” The banner was carried high through the streets of Naples by Spanish soldiers and hung ceremoniously from the mainmast of the

Real.