Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 (66 page)

Read Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 Online

Authors: John H. Elliott

Tags: #Amazon.com, #European History

BOOK: Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830

4.84Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The conflict on North American soil in fact began in 1754, two years before the formal outbreak of war in Europe, when Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia sent a military expedition under the 21-year-old Lieutenant-Colonel George Washington to the further side of the Allegheny mountains in a bid to challenge the assertion of French sovereignty over the Ohio Valley.' As was to he expected, the expansionist plans of the recently formed Ohio Company of Virginia2 had collided with those of the French to establish a permanent presence for themselves and their Indian allies in the vast area of territory between their settlements in Canada and in the Mississippi Valley, and so to block British expansion into the interior. Washington's crushing defeat at Fort Necessity was followed by the despatch in 1755 by the Duke of Newcastle's ministry of Irish infantry regiments under the command of Major-General Edward Braddock - `two miserable battalions of Irish', as William Pitt described them in a speech to the House of Commons; - to expunge the chain of French forts. His expedition, like that of Washington, ended in disaster at the hands of the Indians and the French.

The Duke of Newcastle hoped to confine the conflict to North America, but the dramatic reversal of great-power alliances in Europe created the conditions and the opportunities for a struggle that was to be global in scale. England declared war on France in May 1756, as French warships sailed up the St Lawrence with troops for the defence of Canada under the command of Montcalm.4 Montcalm's energetic direction of military operations forced the English and colonial forces on to the defensive, and it was only after William Pitt was entrusted by a reluctant George II in 1757 with the effective running of the war that vigour and coherence were injected into the British war effort, and the run of defeats was succeeded by an even more spectacular run of victories.

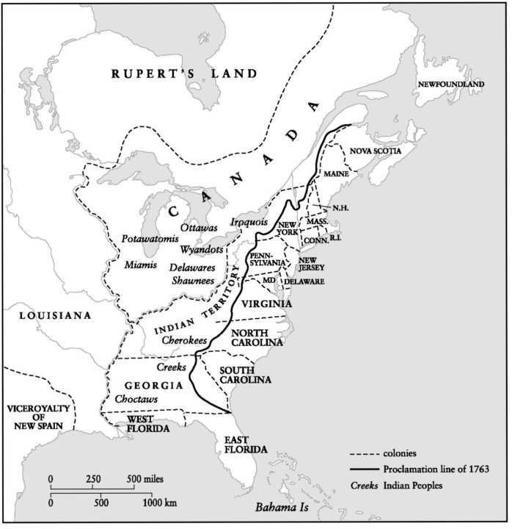

Map 6. British America, 1763.

Based on The New Cambridge Modern History, Vol. XIV, Atlas (1970), pp. 197 and 198; Daniel K. Richter, Facing East from Indian Country. A Native History of Early America (2001), p. 212.

By establishing British naval superiority in the Atlantic, and making North America the principal focus of Britain's military effort, Pitt was able to turn the war around. During the course of 1758 General Amherst captured Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, commanding the mouth of the St Lawrence,' and AngloAmerican forces took and destroyed the strategically commanding Fort Duquesne at the forks of the Ohio. The year 1759 was to be the annus mirabilis of British arms. A naval force in the West Indies seized the immensely profitable sugar island of Guadeloupe; a campaign fought with the help of the Iroquois, who realized that the time had come to switch their support to the English, captured the French forts in the Lake Ontario region; and Quebec capitulated to the troops of General Wolfe. When the last effective French Atlantic squadron was defeated two months later at Quiberon Bay, the chances of French recovery in North America were gone, and with the surrender of Montreal in the summer of 1760 the conquest of Canada was complete. The young George III, ascending the British throne in October of that year, had entered into a rich and vastly expanded imperial inheritance. On both sides of the Atlantic his triumphant peoples could celebrate an unprecedented succession of victories around the world; and there were more to come, both in India and America, where the remaining islands of the French West Indies, including Martinique, fell to British attacks in 1761-2.6

When Charles III succeeded his half-brother Ferdinand VI on the Spanish throne in 1759, the year before the accession of George III, it was already obvious that the balance of global power had tilted decisively in favour of Great Britain. Although courted by both sides, Spain had remained neutral during the opening years of the Anglo-French conflict, but the run of British victories was cause for growing concern to Madrid, and in 1761 the French and Spanish Bourbons renewed their Family Compact. Although this was nominally a defensive alliance, the British government got wind of a secret convention promising Spanish intervention in the conflict after the safe arrival of the treasure fleet, and in January 1762 Britain pre-emptively declared war on Spain.7

Spain's ill-judged intervention was to prove a disaster. In a pair of audacious military and naval operations that testified to the new global dimensions of eighteenth-century warfare, a British expeditionary force sailing from Portsmouth, and joined in the West Indies by regular and provincial troops from North America, besieged and took Havana, the pearl of the Antilles, while another expeditionary force, despatched from Madras to the Philippines, seized Manila, the trading entrepot where Asia and the viceroyalty of New Spain touched hands.'

The almost simultaneous fall of these two port cities - one the key to the Gulf of Mexico and the other to the trans-Pacific trade - was a devastating blow to Spanish prestige and morale. No peace settlement would be possible without the return of Havana to Spain, but the security of Florida and central America was now endangered, and the French minister, Choiseul, was keen for negotiations to begin. Although Britain had achieved a crushing naval superiority, its finances were stretched, and Choiseul found a war-weary British government willing to respond. The Treaty of Paris, which came into effect in February 1763, involved a complex series of territorial exchanges and adjustments that, while recognizing the extent of the British victory, would, it was hoped, give reasonable satisfaction to all three powers involved. Britain retained Canada but restored Guadeloupe and Martinique to France; Spain, in exchange for the return of Cuba, ceded Florida - the entire region east of the Mississippi - to Britain, abandoned its claims to the Newfoundland fisheries, and made concessions on logwood cutting along the central American coast; and the French, to sweeten the pill for their Spanish allies, transferred to Spain their colony of Louisiana, which they themselves were no longer in a position to defend. With France now effectively expelled from North America, Britain and Spain were left to face each other across thinly colonized border regions and the vast expanses of the Indian interior.9

For both these imperial powers, the war itself had exposed major structural weaknesses, which the acquisition of new territories under the terms of the peace settlement would only compound. In London and Madrid alike, reform had become the order of the day. Britain might be basking in the euphoria of victory, but, as ministers in London were painfully aware, its power was now so great that it could only be a question of time before France and Spain again joined forces to challenge its supremacy. How long that time would be depended on the speed with which Charles III's secretaries of state could implement a programme of fiscal and commercial reforms that had been the subject of constant discussion in official circles, and which the government of Ferdinand VI had taken the first steps to introducing in the 1750s. The failure of the defending forces at Havana and Manila brought a new urgency to their task. `The secretaries', it was reported, `... are working like dogs. They are doing more in a week than they previously did in six months."° The long siesta was drawing to a close.

The most pressing problem for both the British and Spanish governments was the improvement of measures for imperial defence. For the victors as for the vanquished, the strains and stresses of war had thrown the inadequacies of the existing system into sharp relief. The central issue for both London and Madrid was how to achieve a fair distribution of defence costs and obligations between the metropolis and the overseas territories in ways that would produce the most effective results. Both empires had traditionally relied heavily on colonial militias for the protection of their American possessions against either Indian or European attack, but as frontiers expanded during the first half of the eighteenth century, and European rivalries on the American continent intensified, the drawbacks of the militia system became glaringly apparent."

The Spanish authorities already made use of regular or veteran troops to man the expanding network of presidios or frontier garrisons, finally numbering 22, along the vast northern frontier of the viceroyalty of New Spain. They also turned to regulars for the protection of the vital harbour of Vera Cruz on the coast of Mexico, raising an infantry battalion in 1740 to reinforce its defences. Over the middle decades of the eighteenth century in the viceroyalty of New Spain, therefore, a small number of regular troops - perhaps 2,600 in all, and widely dispersed on garrison duty - came to supplement the urban and provincial militias on which the viceroyalty's defence had traditionally depended. In spite of an attempt at reform in the 1730s, these militias, which were open to all classes except for Indians, and included companies of pardos (all or part black) '12 were neither organized nor disciplined, and could offer little effective resistance in the event of attack.13 The story was similar in other parts of Spanish America. It was true that over vast areas of the interior of the continent, far removed from the dangers posed by hostile Indians or European rivals, there was little cause for concern. The disasters of 1762, however, exposed the hollowness of a defence system ill prepared either for serious frontier warfare or for amphibious attack.

In the British colonies, with their long frontiers bordering on potentially hostile French, Spanish or Indian territory, and their own growing populations in expansionist mode, the militias were more likely to be put to the test than their Spanish American counterparts. By the eighteenth century, however, their military effectiveness had taken second place to social respectability. Not only Indians, as in New Spain, but also blacks and mulattoes were excluded from the mainland militia companies, and the citizens who manned them were naturally reluctant to commit themselves to the lengthy periods of service demanded by a frontier war that grew dramatically in scale in the 1740s. As a result, the militias had increasingly to be supplemented by volunteer units, drawn from among the poorer whites, and unwillingly paid for by colonial assemblies which had a visceral dislike of voting taxes.14

Although the colonies made an intensive effort in the 1740s to get their militias and volunteer units out on campaign, their military record was mixed, and looked even less satisfactory when subjected to the cold critical scrutiny of British professional soldiers and government officials. Where the viceroys of New Spain and Peru, although with limited financial resources at their disposal, could make, in their capacity as captains-general, such provisions for defence as they considered necessary, the thirteen governors of the mainland colonies of British North America had the difficult preliminary task of negotiating with assemblies that were all too likely to be truculent. The Board of Trade was growing increasingly concerned that Britain's American empire was in no position to repulse a sustained onslaught from New France. Provincial politicking and the ineptitude of military amateurs were putting Britain's valuable North American empire at risk. In deciding in the 1750s, therefore, to commit regular troops to the defence of its transatlantic possessions the British government embarked on a major change of policy. By the end of the decade twenty regiments from the home country were to be stationed in America."

In spite of the growing British commitment to the defence of North America, there was a not unreasonable expectation that the king's American subjects should do more to defend themselves. This involved a much greater degree of mutual co-operation than they usually managed to achieve. While in the northern colonies the danger from the French and the Indians had fostered a tradition of mutual assistance in emergencies, the intensity of inter-colonial jealousies and rivalries made it difficult, if not impossible, for all thirteen colonies to act in unison. Even before the formal outbreak of war between Britain and France in 1756, however, the urgency of the need for common defence measures was becoming apparent to observers on both sides of the Atlantic. In June 1754 the Board of Trade was informed that the king thought it highly expedient that `a plan for a general concert be entered into by the colonies for their mutual and common defence', and ordered the Board to prepare such a plan.16 In America itself, Benjamin Franklin, who had become the eager apostle of a great British empire in America, drafted a `Plan of Union' for submission to a congress convened in Albany in 1754 on the instructions of the Board of Trade for the co-ordination of the Indian policies of the different colonies. Franklin's plan was ambitious - too ambitious for colonies historically jealous of their own rights and traditions, and deeply suspicious of any scheme involving the surrender of some of the most cherished of those rights to a `Grand Council' of the colonies, meeting annually and empowered not only to negotiate on their behalf with the Indians, but also to levy taxes and raise troops for colonial defence. When the plan was brought before the colonial legislatures, most of them rejected it out of hand, and some did not even consider it.'7 The idea of unity was not one that came instinctively to societies born and bred in diversity.

Other books

Domme By Default by Tymber Dalton

Indigo Magic by Victoria Hanley

Just Between Us by J.J. Scotts

Mistletoe Magic by Lynn Patrick

The Race for the Áras by Tom Reddy

Unexpected Christmas by Samantha Harrington

Thresh: Alpha One Security: Book 2 by Jasinda Wilder

The Gladiator's Prize by April Andrews

3 Can You Picture This? by Jerilyn Dufresne

Ani's Raw Food Essentials by Ani Phyo