Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 (47 page)

Read Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 Online

Authors: John H. Elliott

Tags: #Amazon.com, #European History

BOOK: Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830

5.02Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

20 Anon. Plaza Mayor de Lima (1680). The painting testifies both to the splendour and preeminence of the viceregal capital, and to the diversity of the city's population. Behind the fountain at the centre of the Plaza Mayor rises the cathedral, with its baroque facade. Beside it stands the archbishop's palace, and, to the left of the painting, on the north side of the square, the viceregal palace. The proximity of the two palaces suggests the close union of church and state. The numerous figures in the plaza cover the spectrum of Peruvian colonial society, from members of the Spanish and creole elite, in carriages or on horseback, to Indian women selling food and fruit in the market and African water-sellers filling their jars.

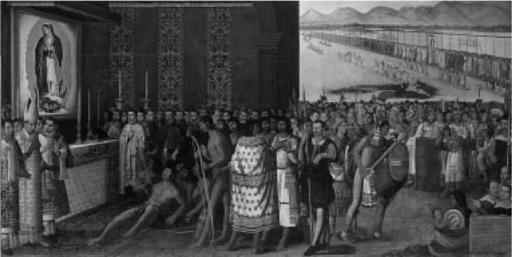

21 A representation (1653) of the transfer in 1533 of the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe to its first chapel in Tepeyac, outside Mexico City. The two `republics' of Spaniards and Indians are clearly distinguished. In the Virgin's first miracle an Indian is cured, after being accidentally wounded by an arrow in a mock battle of Aztecs against Chichimecas. Her image is shown in the background being brought across the causeway to Tepeyac.

22. Anon., Return of Corpus Christi Procession to Cuzco Cathedral (c. 1680). The Spanish American city as the scene of open-air religious theatre. One of a series commissioned by the bishop of Cuzco showing different stages of the procession, which took place in a period of renewed civic confidence and splendour following the city's recovery from a devastating earthquake in 1650.

The antipathy was liable to come to a head during the elections periodically held for the appointment of priors, provincials and their councils. During the seventeenth century these elections came increasingly to pit creoles against peninsulares, and aroused the most intense passions not only in the religious houses themselves but throughout a society in which everyone had a relative in the religious life. `Such were their various and factious differences', wrote Thomas Gage of the election of a provincial for the Mercedarians, `that upon the sudden all the convent was in an uproar, their canonical election was turned to mutiny and strife, knives were drawn, and many wounded. The scandal and danger of murder was so great, that the Viceroy was fain to interpose his authority and to sit amongst them and guard the cloister until their Provincial was elected.'88

Both locally and in Rome the Spanish-born friars fought hard to prevent their orders in the Indies from being taken over by the creoles, and found a weapon to hand in the alternativa, which could be used to impose the regular alternation of creoles and peninsulares in election to office. The alternativa - or, for the Franciscans, a ternativa, stipulating the succession in turn of a peninsular who had taken the habit in Spain, a peninsular who had taken it in the Indies, and a creole - was to become a source of growing irritation to the creoles as they became the majority element in the orders. It also became an important political issue as viceroys sought to impose the system of alternation on different religious communities in a desperate attempt to keep the peace.89

Regular versus secular clergy, order against order, creole against native-born Spaniard, a state-controlled church all too often impervious to state control - these different sources of tension, conflicting and combining, ran like a series of electric charges through Spanish American colonial life. Storms could blow up very rapidly, as they did again in New Spain twenty years after the downfall of Gelves, when the Bishop of Puebla, Juan de Palafox, renewed the campaign for the secularization of parishes in his diocese, and became embroiled in a violent dispute with the Jesuits over their refusal to pay tithes. Once again the viceroyalty lurched into a major political crisis, with Palafox receiving the acclaim of the creoles, not least for his efforts to open up to them parishes controlled by religious orders which too often seemed unresponsive to creole aspirations.90 Yet, if animosity and vituperation abounded, the church could call on vast reserves of loyalty in a society where the Inquisition - less energetic than its peninsular coun- terpartN1 - exercised its policing activities over a colonial population well insulated from the danger of competing faiths by geography and the strict control of emigration in Seville.

The loyalty was inculcated from an early age by a church whose doctrines and ceremonial were woven deeply into the fabric of daily life. The wealth generated by the mining economies of the two viceroyalties made it possible to sustain a continuing programme of church building and refurbishing. In the nine years following his nomination as Bishop of Puebla in 1640, Palafox brought to a triumphant conclusion the construction of the city's magnificent cathedral, with the use of a labour force of 1,500 and at a cost of 350,000 pesos. This most austere of men had no compunction in devoting massive resources to a building that would proclaim to the world the glory of God and the power of His church.92 Everywhere, elaborate altarpieces and a profusion of images were the order of the day. Of the churches in Mexico City in the 1620s Thomas Gage wrote:

There are not above fifty churches and chapels, cloisters and nunneries, and parish churches in that city, but those that are there are the fairest that ever my eyes beheld. The roofs and beams are in many of them all daubed with gold. Many altars have sundry marble pillars, and others are decorated with brazilwood stays standing one above another with tabernacles for several saints richly wrought with golden colors, so that twenty thousand ducats is a common price of many of them. These cause admiration in the common sort of people, and admiration brings on daily adoration in them to these glorious spectacles and images of saints.93

The spectacle was carried out of the church doors into the streets in the innumerable processions which filled the liturgical year. Writing of the cult in Lima in his Compendium and Description of the West Indies, the early seventeenthcentury cosmographer Antonio Vazquez de Espinosa observed that `in few parts of Christendom is the Holy Sacrament brought out to such an accompaniment, both of priests ... and populace ... all in a vast concourse, and with universal devotion at whatever hour of day or night . . .' (fig. 22).94 The participation in these great processions not only of the civil and ecclesiastical authorities but also of the guilds and confraternities, competing with each other in the liberality of their contributions and the splendour of their floats, helped further to lock great sections of the populace into the ceremonial apparatus - and, with it, the ideology - of a state church in a church state.95

Inevitably the construction and adornment of churches, the maintenance of the cult and the upkeep of a large and imposing clerical establishment made continuing demands on the energy and resources of colonial society, of a weight and on a scale simply not to be found in British North America. Tithes, conceded in perpetuity by the papal bull of 1501 for the upkeep of the church in the Indies, were the foundation of the church's finances.96 Even if there was continuing uncertainty and confusion over the liability for tithes of land held by Indians,97 the growth of a prosperous agricultural economy meant a large and continuous flow of funds into the coffers of the church. These were supplemented by the usual fees for baptisms, weddings, funerals and other ecclesiastical services. The religious orders were dependent on alms-giving and charity, and their activities were financed by a vast outpouring of donations and pious bequests from creoles, mestizos and Indians alike.NB

The willingness of this population to found chaplaincies and convents, endow masses in perpetuity and leave property in its wills for the support of religious and charitable activities was both an expression of its devotion to a particular order or cult, and a form of spiritual investment promising longer-term if less immediately tangible benefits than the appropriation of wealth for secular activities. Founders and patrons of convents, for instance, could expect constant prayers to be offered up for the salvation of their souls and those of their family. In a society, too, in which identities were affirmed and status measured by conspicuous expenditure, spectacular expressions of piety performed an essential social function. Religion, status and reputation were intimately related and mutually reinforcing in Spanish American colonial society, and the pious benefactions which created a close association between a family and a particular religious institution bought for it not only spiritual benefits but also social prestige.99

But there were other, and more easily calculated benefits, too, to be gained from investment in the faith. As a result of the continuous flow of gifts and legacies, the church, in its various branches, became a property-owner on a massive scale. By the end of the colonial period 47 per cent of urban property in Mexico City belonged to the church,100 and the religious orders, with the exception of the Franciscans, acquired large tracts of profitable land through donations, purchase and transfers.101 By the time of their expulsion in the eighteenth century the Jesuits, as the most successful landowners of all, owned over 400 large haciendas in America, and controlled at least 10 per cent of the agricultural land of what is now Ecuador.102 Religious institutions thus became involved, either directly or indirectly, in estate management, and were often liable to find themselves with funds surplus to their immediate needs. With money to spare, once they had met the obligation imposed on them by the Council of Trent to be self-financing, they naturally sought outlets for the investment of their surplus capital. As a result, even in seventeenth-century Peru, unique in Spanish America for its seven public banks founded between 1608 and 1642, the church emerged during the course of the seventeenth century as a major - and frequently the major - supplier of credit in a society short on liquidity.103 Landowners, merchants and mining entrepreneurs would turn to ecclesiastical institutions for loans, in order to invest in new enterprises or simply to keep afloat, and those already possessing close family links with some religious foundation - through patronage, endowments and the presence of relatives as friars and nuns104 - clearly enjoyed privileged access to the facilities they could offer.

Since church teaching on usury made it impossible for convents and other religious institutions to advance money on interest, an alternative device - the censo al guitar - was imported from Spain. The prospective borrower, offering the institution a censo or fixed rent on a piece of property, effectively contracted to provide it with an annual return, disguised as an annuity payment, on the sum advanced. The rate of return, which was fixed by the crown, stood at 7.14 per cent in the later sixteenth century, but was reduced to 5 per cent by a royal decree of 1621.105 The collateral was provided by real estate. This had major implications for the colonial economy. The owners of haciendas and rural estates might find up to 60 or 70 per cent of the value of their properties swallowed up in payments to the church.106 Not all of this burden was the result of borrowing. A significant portion came from the encumbering of properties with censor established for the upkeep of capellanias or endowed chantry funds which would pay a priest to say a number of masses every year for the soul of the founder and other family members.107 But in both instances the effect was to channel rural wealth into the cities for the upkeep of urban clerics; and failure to meet the annual payments on loans could result in the passing into ecclesiastical hands of the property used as a collateral.

Already by the end of the sixteenth century concern was being expressed about the massive accumulation of real estate by the church,108 but it was not until the eighteenth century and the introduction of the Bourbon reforms that its power and resources would be clipped. The effects of mortmain, however, were not as uniformly negative as the eighteenth-century reformers liked to assert. If the various agencies of the church absorbed a substantial proportion of colonial resources, these at least remained in the Indies themselves, whereas the bulk of the crown's American revenues were remitted to Spain.'09 Within the Indies, the church's assets could benefit the local economy in various ways. It was in its own right a large-scale employer of labour, for the construction of cathedrals, churches and convents, while the credit facilities that it was able to offer could be used to finance economically or socially productive projects. The religious foundations, too, could be highly efficient landowners. In general they placed their rural estates in the hands of administrators, but the Jesuits preferred to involve themselves directly in exploiting the possibilities of the agricultural and grazing lands that passed into their possession, and proved themselves shrewd business managers when it came to developing important enterprises like sugar mills and textile workshops.`0

Other books

Plata by Ivy Mason

Chainfire by Terry Goodkind

Inside Straight by Banks, Ray

Jayne Castle [Jayne Ann Krentz] by Crystal Flame

Marry in Haste by Jane Aiken Hodge

Wolf Hunt (Book 2) by Strand, Jeff

The Africans by David Lamb

Current by Abby McCarthy

Greco (Book 1.5) (The Omega Group) by Andrea Domanski

Grizzly Love by Eve Langlais