Empire of the Sikhs (7 page)

Read Empire of the Sikhs Online

Authors: Patwant Singh

But the head-hunters' policies made the Sikhs even more determined to make the administration pay for its misdeeds. Zakariya Khan, disconcerted by the unending plunder of his treasuries and arsenals and the loss of a number of his men, now tried appeasement. In 1733 he offered the Sikhs a large

jagir

or gift of land, which they willingly accepted. This proved a major error from the Mughal point of view. The Sikhs saw an opportunity for rigorous institutionalization of their activities that concerned the larger purpose of safeguarding the faith and its followers from genocidal Mughal attacks. Kapur Singh was the man chosen to head this programme. A tough, self-assured and experienced warrior, he was also deeply devout and dedicated to building solid institutions that would protect the Sikhs.

He organized the Sikhs into different groupings or

dals,

which would later be merged into the Dal Khalsa. The

dals

had responsibilities ranging from armed resistance against the Mughals and guarding Sikh places of worship to attending to conversions and baptisms. The Taruna Dal, composed of younger men, relished the opportunity of dealing with the Mughal military; the years of

Mughal oppression had hardened Sikh farmers into a motivated potential soldiery, able-bodied men keeping lance and sword by them as they worked on their land. As its membership increased to 12,000, it was further divided into five sections, each having its own commander with his banner, drum and administrative control of the territories annexed by him.

These five sections, along with several more that would be formed as time went on, were to lead to the formation of the Sikh

misls.

The word

misl

in Arabic means âequal'; the term was first used by Guru Gobind Singh in 1688 when he organized the Sikhs into a battle formation of groups each under its own leader, with equal power and authority. These groups eventually took the form of twelve

misls,

which derived their names from their villages or leaders: Ahluwalia, Bhangi, Ramgarhia, Faizullapuria, Kanaihya, Sukerchakia, Dallewalia, Shahid or Nihang, Nakkai, Nishanwalia, Karorsinghia and Phulkian. The

misl

chiefs, the Sardars, who have been compared to the barons of medieval times, had complete control over their territories, and their military units were able to discourage any defiance of their authority. They had absolute autonomy, but in times of war they pooled their resources to take on the enemy. In times of peace they often fought each other.

The

misl

warrior was a soldier of fortune, a horseman who owned his own mount and equipment, armed with matchlock, spear and sword. Infantry and artillery were virtually unknown to the Sikhs for serious purposes before the days of Ranjit Singh. Sikh soldiers despised âfootmen' who were assigned the meaner duties â garrison tasks, provisioning, taking care of the women. âThe Sikh horseman', according to Bikrama Jit Hasrat, âwas theoretically a soldier of the Khalsa, fired by the mystic ideals of Gobind which he little understood, and he had no politics. He was also a soldier of the Panth [Sikh community], out to destroy the enemies of the Faith in all religious fervour and patriotism. Above all, he was a free-lance, a republican with a revolutionary impulse ⦠The

armies of the Dal Khalsa, unencumbered by heavy ordnance, possessed an amazing manoeuvrability. [They] were sturdy and agile men who could swiftly load their matchlocks on horseback and charge the enemy at top speed, repeating the operation several times. They looked down upon the comforts of the tents, carrying their and their animals' rations of grains in a knapsack, and with two blankets under the saddle as their bedding, they marched off with lightning rapidity in and out of battle.'

27

At the height of their power in the latter part of the eighteenth century, the

misls

could muster around 70,000 such horsemen.

The Sikhs at this time accounted for only 7 per cent of the population of the Punjab, as against 50 per cent Muslims and 42 per cent Hindus.

28

Before their golden period they had to face huge and continuing adversity. To start with, Zakariya Khan, having given them a

jagir

as a peace offering, sent a force two years later to reoccupy it. He took Amritsar by siege, plundered the Harmandir Sahib, filled the pool with slaughtered animals and desecrated its relics.

When Zakariya Khan died in 1745 and his son Shah Nawaz Khan succeeded him as governor of Lahore, the progeny proved even worse than the parent. Nawaz Khan's favourite pastime appears to have been to watch the bellies of captive Sikhs being ripped open and iron pegs stuck into their heads. In June 1746 the first of the two so-called

ghalugharas

(disasters) took place: a large body of Mughal troops under Yahiya Khan massacred 7,000 Sikhs while an additional 3,000 were captured and taken to Lahore for public execution. The

wada ghalughara

or great disaster â to be described â took place in February 1762, perpetrated by the Afghan invader Ahmed Shah Abdali.

The sixteen years between the two

ghalugharas

saw copious bloodshed in the Punjab, with the forces of the Khalsa continually set upon by one or another of their three principal enemies â the invaders Nadir Shah of Persia, the Afghan leader Ahmed Shah Abdali and the Mughal emperor. Abdali invaded India eight

times between the years 1748 and 1768. Punjab now became the setting for a triangular struggle between the Afghans, Sikhs and Mughals. Abdali and the Mughals wanted to see the end of the Sikhs, but the Khalsa was willing to take on both. Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, head of the Ahluwalia

misl,

liberated the Golden Temple from Mughal control and restored the shrine to its former glory. In 1752 the new governor of Lahore, Mir Mannu, a particularly duplicitous and sadistic man who had defected from the Mughals to the Afghans and who was keen to curry favour with Abdali, now officially declared Punjab an Afghan province, in defiance of the declared Sikh sovereignty over several regions and towns of Punjab dating from Banda Singh's time.

When in 1757 the Sikhs waylaid Abdali's baggage train full of the wealth he had plundered from Delhi, Mathura and Vrindavan, rescued hundreds of captive Hindu girls and returned them to their homes, it was the last straw for him. He ordered his son Timur Shah, now governor of Lahore, to eliminate the âaccursed infidels' and their Golden Temple once and for all.

Attacks and counter-attacks between the Sikhs and their persecutors formed a continuing dance of death on the landscape of Punjab, culminating in the

wada ghalughara

on 5 February 1762. In a surprise attack on a large assembly of Sikhs at Kup near Sirhind, Abdali's army, having covered 110 miles in two days, killed from 10,000 to 30,000 Sikhs (estimates vary), a very large number of whom were women and children who were being escorted to a safer region. In the ferocious fighting the odds were heavily loaded against the Sikhs.

Abdali now headed for the Golden Temple and struck on 10 April 1762, at a time when thousands had gathered there for the Baisakhi celebrations. The bloodbath was horrific. The Harmandir was blown apart with gunpowder. The pool was filled with the debris of destroyed buildings, human bodies, carcasses of cows and much else, and topping it all a pyramid of Sikh heads was erected.

Within a few months, however, early in 1763, Charat Singh, head of the Sukerchakia

misl

â whose grandson Ranjit Singh was to be born one and a half decades later â managed to wrest back control of the Golden Temple.

The very next year, however, Abdali was back in India and once more bore down on the Sikh shrine. Each of the thirty Sikhs present died defending the sacred edifice, which was yet again demolished and defiled. But this was the last time the Afghans or the Mughals would ever set foot in it. In a swift military action the Sikhs not only annexed Lahore on 16 April 1765 but declared their sovereignty over the whole of Punjab. To make absolutely clear that political power in the region now rested with them, they struck coins and declared Lahore the mint city,

Dar-ul-Sultanate

(Seat of [Sikh] Power).

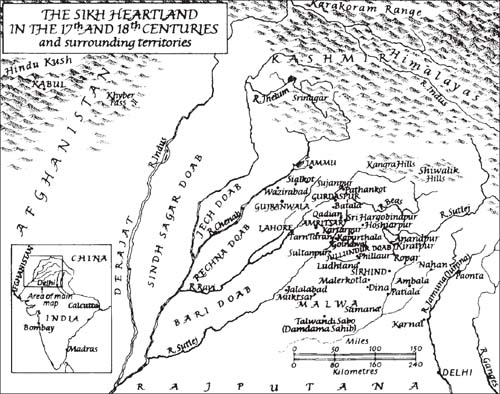

With their control of Punjab, in addition to large parts of what is now Pakistan, plus the present-day states of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Haryana, the Khalsa now emerged as a territorial power of significance and substance. The process was helped by the economic activities of the twelve

misls

which were beginning to prosper as major cultivators of crops such as wheat, rice, pulses, barley, sugar cane, cotton, indigo and jaggery, in addition to a wide variety of fruit. Nor were manufacturing, crafts, construction of townships or internal and external trade neglected. Exports were sent to Persia, Arabia, Yarkand, Afghanistan, Chinese Turkestan, Turfan and Bokhara. Lahore and Amritsar between them also produced increasingly fine silks, shawls, woollen materials, carpets and metalware. The Sikhs, with their entrepreneurial drive and inclination to spend well and indulge themselves fully, were changing the character of the Punjab.

In March 1783 an event took place that would have been inconceivable a few years earlier. A combined

misl

force under Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, outstanding among Sikh chiefs for his qualities

of leadership, entered Delhi, the imperial seat of the once mighty Mughals. Some of the

misl

leaders arrived at the Red Fort which represented Mughal power and walked into the emperor's audience hall, and Jassa Singh Ahluwalia had himself installed on the imperial throne. It was a symbolic move, but its meaning was clear to all. The Khalsa withdrew only after the emperor agreed to an annual tribute, but when he broke his promise in 1785 the Sikhs returned to Delhi and subjugated it once again. They had no wish to take permanent possession of it, but they made the emperor agree to the construction of eight gurdwaras, each built on a site with a special significance for the Sikhs, one of them being Gurdwara Sisganj, on the spot where Emperor Aurangzeb had had Guru Tegh Bahadur, father of Guru Gobind Singh, tortured and beheaded in November 1675.

The Sikh contingents entering Delhi scrupulously maintained the secular and civilized principles of their religious teachings. No orgy of bloodshed was indulged in despite the number of revered Sikhs who had been brought to Delhi over the years to be barbarically put to death by successive Mughal rulers.

The

misls

contributed significantly to the Sikh vision, with its moral underpinnings. Each of them consolidated Sikh power in the Punjab by imaginatively developing their territories and providing just administration. âIn all contemporary records, mostly in Persian,' one modern historian points out, âwritten generally by Muslims as well as by Maratha agents posted at a number of places in Northern India, there is not a single instance either in Delhi or elsewhere in which Sikhs raised a finger against women.'

29

And as we have seen, with Sikh rule now established over large parts of the Punjab, its people now experienced a sense of security and a rapid increase in prosperity to a much greater degree than over the past half-century.

Two Afghan rulers, however, were still forces to be reckoned with for the Sikhs: Abdali's son Timur Shah who succeeded him in 1772 and Timur's son Zaman Shah who succeeded him in 1793.

While Timur Shah avoided the Sikhs as far as possible, Zaman Shah during one of his invasions briefly occupied Lahore before being thrown out. But events of this period belong to the young Ranjit Singh's first years of leadership and will be described later.

The eighteenth century was a costly one for the Sikhs. It has been estimated that Guru Gobind Singh, in his battles with the Mughals, lost about 5,000 men and Banda Singh at least 25,000; that after Banda Singh's execution Abdus Samad Khan, governor of Punjab (1713-26), killed not less than 20,000 Sikhs and his son and successor Zakariya Khan (1726-45) an equal number; that Yahiya Khan (1746-7) accounted for some 10,000 Sikhs in a single campaign after the

chhota ghalughara,

the first disaster; and that his brother-in-law Muin-ul-Mulk, indulging his sadistic instincts between 1748 and 1753 as governor of Punjab by putting a price on Sikh heads, dispatched more than 30,000. Adeena Beg Khan, a Punjabi Arain, put to death at least 5,000 Sikhs in 1758; Ahmad Shah Abdali and his Afghan governors killed around 60,000 between 1753 and 1767; Abdali's deputy Najib-ud-Daulah, also an Afghan, slew nearly 20,000. âPetty officials and the public' may have killed 4,000.

30

To this total of around 200,000 Sikhs killed over the first seventy years of the eighteenth century must be added the casualties of the clashes with Timur Shah and Zaman Shah.