Empire of Sin (29 page)

Authors: Gary Krist

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #True Crime, #Murder, #Serial Killers, #Social Science, #Sociology, #Urban

“Little Louis” got his first potential break in music at the age of eleven, when Bunk Johnson heard the quartet singing in an amateur contest.

The trumpeter liked their sound, and told his bandmate Sidney Bechet about them. Bechet, who was only fifteen himself at the time, went to hear the quartet and was equally impressed. “

I got to like Louis a whole lot, he was damn nice,” Bechet later wrote. “One time, a little after I started going to hear this quartet, I ran into Louis on the street and I asked him home for dinner. I wanted him and the quartet to come around so my family could hear them.” But Louis seemed reluctant to make the long trip downtown. “Look, Sidney,” the boy said, “I don’t have any shoes … these I got, they won’t get me there.” Sidney ended up giving him fifty cents to get his shoes fixed and made him promise to come. Louis took the money, but then never showed up to perform. Forty-eight years later, Bechet was still annoyed: “It’s a little thing,” he confessed in his 1960 autobiography, “[but] there’s big things around it.” Apparently, the common enemy of Jim Crow had not yet eliminated

all

of the traditional friction between downtown Creoles and uptown blacks. Then again, maybe Little Louis just forgot.

It ultimately took a brush with the law to propel Armstrong into the mainstream of New Orleans music, though at first the incident seemed like a setback. On December 31, 1912, Louis was preparing to do some New Year’s celebrating. He found one of his “stepfather’s” pistols in a cedar trunk, filled it with blanks, and brought it with him when his quartet set out to perform that night in Storyville. As the boys were making their way up Rampart Street, another kid from the neighborhood began shooting a cap gun at them. Knowing he could top this, Louis pulled the pistol from his belt and started shooting back. The policeman standing nearby was not amused. He grabbed the boy and dragged him to jail, where he spent what must have been the most frightening and unpleasant New Year’s Eve he’d ever experienced. The next day, he was brought before a judge in the juvenile court. The verdict: incarceration in the Colored Waif’s Home for Boys for an indefinite term.

It would prove to be the best piece of luck in Louis Armstrong’s entire life.

W

HEN

the Parker brothers first ventured into the dance-hall business on Franklin Street, they were not the only outsiders moving in on what had widely been regarded as Tom Anderson’s turf. The city’s Italian underworld had also seen the profit potential of business in and around Storyville, and they did not hesitate to claim a share for themselves. To state that “

the Mafia moved in on Storyville” would be inaccurate; most serious crime historians doubt that the Italian crime syndicates in New Orleans at this time were organized enough to justify the Mafia title, no matter what the local newspapers might think. But it is true that many of the nightclubs, saloons, and dance halls of the city’s entertainment districts were being taken over by Italians, and many of their surnames—Matranga, Segretta, Tonti, Ciacco—were well known to police as prominent in the criminal doings of the city. It was as if the nemeses of the city’s reformers were closing ranks. Italian criminals and black musicians were, in a sense,

finding refuge in the bastion of the vice lords—that is, in Storyville.

At the same time, the fallout of the Lamana kidnapping of 1907 seemed to have plunged the city’s Italian underworld into disarray. Francesco Genova,

regarded by police as the principal figure in the local Mafia, had left town shortly after being released from jail in the Lamana case, never to return. Some believed that his young lieutenant

Paul Di Christina was now in charge. But this succession of leadership was apparently not satisfactory to Giuseppe Morello up in New York. Sometime in 1908,

the Boss of Bosses traveled to New Orleans for several days of meetings with local criminal leaders. The visit—which ended with Morello parading through the Italian quarter wearing a knotted red handkerchief on his head, a supposed “

Mafia death sign”—had several purposes. It did not go unnoticed in the press, for instance, that a prominent Italian hotelier was stabbed to death within hours of Morello’s return to New York. But the meetings also seemed to signal a change in leadership within the local organization. A letter from Morello (under the pseudonym G. LaBella) to New Orleanian Vincenzo Moreci—dated November 15, 1909, and written in the flowery, ambiguous, falsely humble style of such missives—more than hints at the ongoing shake-up:

“

Dear Friend,” it began. “Am in possession of your two letters, one that bears date of the 5th, the other on the 10th of November. I understand the contents. In regard to being able to reorganize the family, I advise you all to do it, because it seems it is not right to stay without a king nor country. But I authorize you to convey to all [i.e., to everyone] my humble prayer and my weak opinion, but well understood, that those who are worthy and that wish to [belong] should belong; those that do not wish to belong, let them go.”

The recipient of this letter, Vincenzo Moreci, was

a native of Termini Imerese, Sicily. He had emigrated to New Orleans in 1885 and was now an inspector (or “banana-checker”) for United Fruit. Regarded by the

Daily Picayune

as “

an Italian of the better class,” he had actually been a prominent member of the Italian Vigilance Committee that had investigated the Lamana affair.

But there was more to Moreci than the

Picayune

realized at the time, and this was to become obvious over the next several years.

Late one Saturday night in March of 1910,

Moreci was walking down Poydras Street when he was approached by two well-dressed men who pulled pistols out of their belts and fired five shots at him. Two bullets struck Moreci in the head, and he fell to the pavement, seriously wounded, as the two men ran away in different directions. Moreci ended up surviving the attack, and when questioned by police he claimed to have no idea who his assailants were. But it was generally understood that one of the shooters was Paul Di Christina, and that the other was a member of his faction named Giuseppe Di Martini.

This apparent act of rebellion against Moreci was not to go unpunished. One month later,

Di Christina was shot and killed on the street as he was entering his grocery-saloon on the corner of Calliope and Howard Streets. His neighbor, another Italian grocer named Pietro Pipitone, admitted that he had fired the shot, claiming that Di Christina owed him two months’ rent. But given the victim—and the fact that the grocery trade was a favorite cover for Italian criminals—police thought there was more behind the killing. And when, two months later,

Giuseppe Di Martini was also fatally shot—on Bourbon Street, by a man seen moments before in the company of Vincenzo Moreci—it was clear that this back-and-forth series of assassinations and assassination attempts bore all the earmarks of a Mafia power struggle.

Moreci was eventually acquitted of involvement in the Di Martini murder, but the killings went on, most of them involving Italian grocers who had allegedly been threatened by the Black Hand. In July of 1910, grocer Joseph Manzella, who had received several Black Hand extortion letters, was shot to death in his store by a man named Giuseppe Spannazio. In this case, there was a witness—Manzella’s seventeen-year-old daughter, Josephine, who grabbed a small revolver and chased the assailant into the street, where she shot him dead on the banquette. “

I’m glad I killed him,” the unrepentant girl told police. “If he had been arrested, he probably would have been set free within a few months.”

But then came

a series of more mysterious murders that seemed fundamentally unlike those that had come before. They took place in the dead of night, for one thing, and in the privacy of the victims’ bedrooms rather than on the street or in their stores. In August of 1910, grocer John Crutti was brutally beaten with a meat cleaver as he lay sleeping with his wife and children in the residence behind their Royal Street store. Some months later, another grocer, Joseph Davi, was also butchered—again with a cleaver, and again while in bed with his wife (who was injured but survived). In both cases, police had no leads and were able to make no arrests.

Then,

at two

A.M.

on the morning of May 16, 1912, an attack left yet another Italian grocer dead. Antonio Schiambra and his pregnant wife were asleep beside their young son in the bedroom of their home on a lonely stretch of Galvez Street. An assailant climbed through an unlocked kitchen window, made his way down the hallway, and entered the bedroom. As the victims slept, he lifted the mosquito netting over their bed, pressed the barrel of a pistol against the grocer’s torso, and fired five shots. Schiambra died almost instantly, and his wife, who was struck by a bullet that had passed through her husband’s body, was mortally wounded. She was able to crawl to a window and scream for help, but by the time a neighbor arrived, the shooter had escaped.

Police were again baffled, but this time they at least had some clues. While moving two boxes to help him reach the kitchen window, the killer had left a clear footprint in the soft mud around the house’s water cistern. The imprint was of a new shoe, and one “

of the latest and most stylish shape.” Perhaps more important, a neighbor told police about an incident she had witnessed in the Schiambra grocery two weeks earlier. Two Italian men, one of them tall and well dressed, had walked into the establishment. “

Good morning, Mrs. Tony,” the tall man said to Mrs. Schiambra (a form of address that police would later recall when the mysterious “Mrs. Toney” chalk message was found in the Maggio ax murder investigation). Mr. Schiambra asked his wife to leave, and then argued with the two men in Italian for some time. The men finally left, according to the witness, “with scowls on their faces.” But when the district attorney tried to follow up on this suspicious incident, Mrs. Schiambra (who survived for some ten days before succumbing to her bullet wound) was

strangely uncooperative.

“

The Italians of New Orleans,” the

Daily Item

reported in some dismay, “awed by the power of the Black Hand … fear the murderers will become more desperate. They ask, ‘Who will be next?’ ” Assassinations of known mobsters on the street were one thing; but Schiambra, like Crutti and Davi, was apparently a legitimate businessperson, slaughtered in his bed as he lay beside his wife and child. Few in New Orleans had any hope that their police would get to the bottom of these crimes. As the

Daily States

observed a few days after the killing, “

Many theories have been advanced, [but] the Schiambra outrage promises to be listed among the many mysterious cases which have never been solved.”

H

ELPLESS

as they were to control crime in the Italian enclaves of the city, the New Orleans police were having better luck implementing the reformers’ campaign to crack down on Storyville. The passage of

two new laws significantly expanded the arsenal that could be brought to bear against the libertine practices of the Tenderloin. In 1910, the city council passed a bill amending the original Storyville ordinance, strengthening restrictions against lewd dances in brothels and beefing up penalties for all other infractions. State laws passed that same year toughened the

prohibition against interracial concubinage and other forms of contact across the color line. Though the state legislature declined to put a strict definition on the term “colored,” reformers like Philip Werlein hoped to use the new laws to put the Basin Street octoroon houses out of business for good.

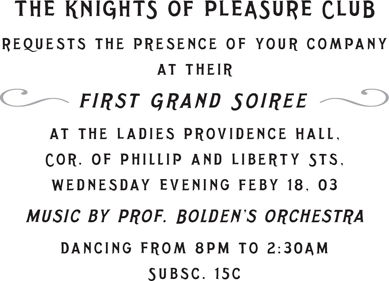

Meanwhile, Gay-Shattuck was also being used more effectively as a weapon for reform. Shortly before Mardi Gras in 1911, Tom Anderson’s persistent scourge—Dr. S. A. Smith, superintendent of Louisiana’s Anti-Saloon League—launched a campaign against that most cherished of Storyville traditions, the French ball. On the day before Anderson’s Ball of the Two Well Known Gentlemen, the district attorney, under heavy pressure from reformers, announced that the provisions of Gay-Shattuck would be strictly enforced. In other words, if women were present at the ball, no liquor could be served, and vice versa. According to the announcement, “

No subterfuges [would] be tolerated.”