Emily's Runaway Imagination (7 page)

Read Emily's Runaway Imagination Online

Authors: Beverly Cleary

By this time everyone seemed to be well supplied with cream and sugar, so Emily set her tray on the tea table and slipped around the edge of the room to the library corner. “Mama, did you save me a book?” she asked.

“There are still books left to choose from,” answered Mama.

And there were! Just think of it, real library books right here in Pitchfork, Oregon.

The Dutch Twins, The Tale of Jemima Puddleduck

âwhat a tiny book that was! Emily had not known they made such little books.

The Curly-haired Hen, English Fairy Tales

. But no

Black Beauty

. Oh well, perhaps

another time. Emily chose

English Fairy Tales

because it was the thickest, and Mama wrote her name on a little card that she removed from a pocket in the book. Emily now had a library book to read. She could hardly wait to write to her cousin Muriel in Portland.

Emily had settled down in a slippery leather armchair to begin her book, when something made her glance toward the top of the stairs. A strange boy about Emily's age stood in the doorway. He was wearing clean faded overalls and his hair must have been cut with a pair of dull scissors by his father. He looked uncertainly at the ladies' hats and the tea table and turned to leave.

“Won't you come in?” asked Mama, with a smile.

The boy was glad to have someone welcome him. Shyly he approached Mama's table. “Ma'am, is it all right if I get some books for my family?” he asked.

Mama smiled at the boy. “I don't believe I have seen you in Pitchfork before. Do you live in the country?”

“No, ma'am. I live in Greenvale,” he answered. “We read about the library in the

Pitchfork Report

and I walked down the railroad track to see if we could get some books too.”

“Why, that's at least four miles,” said Mama, “and four miles back again.”

The boy looked at the floor. “Yes ma'am.”

“Of course you may take books for your family,” said Mama. This boy wanted to read. That was enough for her. It made no difference where he lived.

Emily watched while the boy, oblivious to everyone else, selected his books with care. A book about wild animals. That must be for himself.

The Tale of Jemima Puddleduck

for a little brother or sister. Two grown-up books that must be for his mother and father.

When Mama had written his name on the little cards, the boy pulled a clean white flour sack out of his hip pocket, unfolded it and carefully put the books inside. “I'll take good care of them, ma'am, and bring them back next Saturday.”

“I hope you enjoy them,” said Mama, watching the boy as he slipped through the crowd and disappeared down the stairs. “Just think, that boy is willing to walk eight miles along a railroad track for books,” she remarked, and Emily thought that Mama looked both happy and sad at the same time.

Gradually the crowd drifted away, until at last only Emily and the members of the Ladies' Civic Club were left. The ladies gathered around the table Mama was using for a desk to watch Mama count the pieces of silver that people had given to the library. Sixteen dollars and twenty cents. It seemed like a lot of money to Emily, but Mama

looked disappointed. She sighed, and said, “The people in our town just don't have much money to give to a library.”

The ladies of the Civic Club said they must not be discouraged. Next time they would try a whist party. They would have a real library yet. Look at the books that had circulated that afternoon. Why, a lady way out in the country had even sent a note by a neighbor, asking for a nice cheerful book. And that boy who asked for a book on forestry, and the man who wanted a book on Oregon historyâ¦. Didn't this show that the people of Pitchfork really wanted a library?

“And the boy with the white flour sack,” Emily whispered to Mama. “Don't forget him.”

“Especially the boy with the white flour sack,” agreed Mama. “For that boy we must get a library started.”

And me, thought Emily. I still want

Black Beauty

. She picked up Fong Quock's tarnished silver dollar. “Mama, do you suppose this really is the first dollar he ever earned?”

Mama laughed. “Oh Emily, that is just an expression. You know how people talk. I am sure it isn't his first dollar because he has been supporting his family in China all these years.”

Emily was astonished. She had thought all along that Fong Quock was a bachelor like Pete Ginty. “Then what was he doing here in Pitchfork?” she asked.

“He came to Oregon to seek his fortune,” said Mama, locking up the china closets even though they were almost empty of books. “Many Chinese did in the old days and somehow he found his way to Pitchfork and stayed. I can't say I blame him. It is a beautiful spot, even if the pioneers did name it Pitchfork.”

To seek his fortune! Like Dick Whittington in one of the readers at school. “Do

you think he found his fortune?” Emily asked doubtfully, because Pitchfork seemed to her an unlikely place to seek one's fortune. There were no streets paved with gold and no Lord Mayor, just Main Street paved in concrete, and Uncle Avery at the post office.

“I don't know,” answered Mama, gathering up her handbag and the book she had chosen for herself. “Perhaps he did. He owns his little house and until he sold it not long ago he had a prosperous little business. At least he has been able to send money back to China all these years. Fortune means different things to different people, you know.”

Emily hugged her book and thought this over as she and Mama descended the stairs to the sidewalk. Mama was right, she decided. Fortune did mean different things to different people. And to Emily right now, fortune meant not streets paved with gold

or money to send to China. It meant the people of Pitchfork having enough money to give some to the library. Enough for real book shelves and an encyclopedia and some left over for

Black Beauty

.

The Scary Night

A

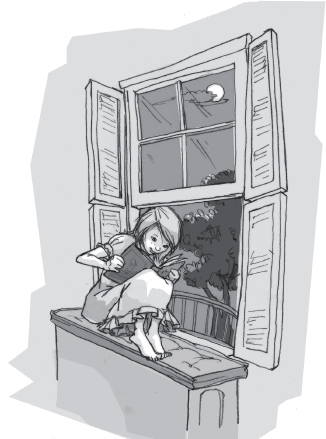

library made a difference. Emily read her book of English fairy tales every minute she could find. She even sneaked the flashlight upstairs and read under the covers until Mama caught her at it. Fortunately there was a full moon and after Mama went downstairs again to read her own book, Emily was able to lean out the window and read by moonlight until she finished her chapter. The dove that turned into a

handsome young man, the girl who had to bring water from the well in a sieve, the old woman whose pig would not go over the stileâEmily loved every word. Best of all she enjoyed scary stories, the tales of giants

and ogres and the one about the fair young woman with the golden arm who turned into a ghost. That was a spooky story. There had never been any scary, spooky stories in any of Emily's readers.

The book Mama was reading was a book of poetry and that made a difference, too, because now Mama went about her work reciting instead of singing. Mama would recite,

“I remember, I remember

The house where I was born,

The little window where the sun

Came peeping in at morn.”

Emily could just picture Mama as a little girl waking up in the morning in a house back East. But Emily's favorite poem was a different one.

Â

“Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,”

Mama would say in a spooky voice as she fried the potatoes.

“While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of someone gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.”

The way Mama said it gave Emily a shivery feeling between her shoulder blades. It was the scariest thing Emily had ever heard and she enjoyed every word of it, although she did not entirely understand it. The poem was about a raven that kept saying, or rather quothing, “Nevermore.” “Quoth the Raven, âNevermore,'” was the

way many of the stanzas ended.

“Say the spooky poem again, Mama,” she would ask, and then shiver deliciously as Mama recited,

“Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.”

Emily enjoyed spooky things when she knew she really had nothing to be scared about. Perhaps that was why Emily decided a spooky evening would be fun when her cousin June came to spend the night with her, or perhaps it was the still, expectant feeling of that hot, hot day that made her feel that something was about to happen. She decided that when bedtime came she and June could go upstairs to bed and tell spooky stories about witches and ghosts and

have a good time scaring each other.

That is, they could if June would cooperate, but knowing June, Emily could not be sure of this. In school when Miss Plotkin led the singing she instructed the class to enunciate so that each word was distinct: “Ring out, ye bells.” Emily and the rest of the class opened their mouths and moved their lips so that each word was separate from every other word. Ringâoutâyeâbells. Not June. She sang loud and gleefully, “Ring

ow

chee bells.” That was June for you. “Ring

ow

chee bells.”

That evening after supper June, carrying her rolled-up nightgown and her toothbrush, was brought to Emily's house by Uncle Avery and Aunt Bessie, who were on their way to a whist party. “Hello, Emily,” she said, when Emily opened the door, and Emily could tell from the way she said it that June was excited to be spending the night

away from home. That was a good sign.

Then Emily discovered that this was the night Daddy had to go uptown for band practice. That made it even better. There was something scary about being alone in the great big house with Mama, something scary but cozy, too. Sometimes Emily enjoyed having Mama all to herself, although of course tonight June would be there, too.

Daddy practiced his solo,

Sailor, Beware

, on his baritone horn a couple of times before he went uptown to join the rest of the boys, as the men in the Pitchfork band were called. Everyone hoped that the band, which played at the State Fair and the Livestock Exposition, would help put Pitchfork on the map, although Emily knew that Pitchfork was already on the map. She had looked in the atlas at school and there it was, a tiny dot on the map of Oregon.

When Daddy had gone, Mama began to

read her library book while Emily and June studied the Montgomery Ward catalog to see what they would buy if they had any money. Emily looked, as she always did, at the picture of the rotary eggbeater, which could whip cream in no time at all. After that, she and June had difficulty looking at the catalog together, because Emily wanted to look at the beautiful toys some people must have enough money to buy and June wanted to look at all the different auto robes, many of them like real Indian blankets. Finally Emily let June take the catalog, because she was company. She herself looked at the book of wallpaper samples and pretended she could buy new wallpaper for the whole house. She would start with the downstairs bedroom, where a pattern of yellow roses would be pretty. Yellow was Mama's favorite color. She always said yellow was so gay.

Out on the back porch Plince whined

and scratched at the screen door.

Mama walked from the sitting room into the dining room and called, “What's the matter, Plince?”

Plince whimpered and tried to open the screen door with his paw.

Spooks, thought Emily. Plince must be scared of spooks.

“Now Plince, you run along and sleep in the woodshed the way you always do,” Mama said, as she closed the door. Dogs were not allowed in the house any more than pigs or cows. They belonged outdoors.

“Plince sounded scared of something, didn't he?” Emily remarked when Mama sat down again.

“Now Emily,” said Mama, “don't let your imagination run away with you.” She said it with a smile, because Mama understood what many people did notâit was fun to let one's imagination run away. It made life exciting to let one's imagination go galloping

off just the way a real horse had once made Mama's life pretty exciting for a while.

Emily decided it was time to produce the treat she had been savingâbananas! Grandpa had a whole bunch hanging in the window of his store, and when he heard that June was going to spend the night with Emily he had given Emily two bananas for a treat. When Emily went out to the kitchen to get them, Plince whined and scratched at the screen door once more.

The two girls peeled their bananas and began to eat. Emily ate with little bites, chewing as slowly as she could, to make the precious fruit last as long as she could. June bit off big pieces of the banana. “It tastes so much better in big bites,” she explained.

“But it doesn't last as long,” protested Emily.

“But it tastes better while it does last,” said June.

“Now Emily,” said Mama, “you can't

expect everyone to enjoy eating bananas the same way.”

Of course she could not, but Emily wished she and June could do something the same way just once. If Muriel were here, she would understand immediately how a banana should be made to last as long as possible, even though in Portland she probably had bananas every day if she wanted them.

Plince persisted in scratching at the screen door. “Plince, stop that!” ordered Mama. The dog stopped scratching and began to whimper.

“Plince is a fraidy-cat,” said June.

“You mean fraidy-dog,” said Emily, and both girls giggled.

When the bananas were eaten, Emily turned to her mother. “Say the poem again. The spooky one.”

Mama closed her book. “Just one verse,” she said, and began, “âOnce upon a midnight

drearyâ'” while outside a lilac bush began to scratch at the window as if it too wanted to come inside, and the curtains stirred in a ghostly way. When Mama finished the verse she said briskly, “Now off to bed you go.”

“Just one more verse,” begged Emily.

“Scoot,” said Mama.

The girls washed their faces and brushed their teeth at the kitchen sink and tonight, because she had a guest, Emily picked up the flashlight to guide the way upstairs. Usually she went alone through the long dark hall and up the long dark flight of stairs to the dark bedroom and thought nothing of it. The house was dark, because each room had just one electric light hanging by a cord from the middle of the ceiling. The ceilings were high and all the Bartletts except Mama, who after all was not born a Bartlett, were tall people, so the lights were too high for Emily to reach without standing on a chair.

Mama could barely reach them by standing on tiptoe. The tall Bartletts had not wanted lights hanging where they could bump into them in the dark.

In the farthest bedroom the girls bounced into bed and pulled the quilts up under their chins, because now a cool breeze was blowing through the house. Emily played the flashlight around the big room. Its weak light made the white iron bedstead, the only furniture in the room, look ghostly. Even the windows, which had inside shutters instead of curtains, looked like oblong eyes in the night. “Isn't it scary?” whispered Emily. “And did you notice there was something funny about the way Plince wanted to come in the house?”

“Probably he just wanted a banana,” scoffed June.

“Dogs don't eat bananas,” said Emily, thinking that Muriel would have been a

much more satisfactory cousin to be spending the night. Muriel would have enjoyed huddling in the middle of the bed making up ghost stories. June's imagination would never run away with her; she had an imagination likeâlike a plow horse.

The old house made a snapping noise. “I'll bet that was a ghost walking across the roof, wringing its hands,” whispered Emily, trying to work up a good shiver in spite of June.

“It's the temperature changing,” said June. “You know your house always makes noises when it begins to cool off.”

This was the sort of thing Emily might have expected from matter-of-fact June, who was not entering into the spooky spirit of things. Emily tried again, still whispering because she had heard Mama come upstairs to bed. “Did you know this house has

thirteen

rooms?”

“Well,” said June, “our great-grandfather had a big family. He needed a lot of rooms.”

Oh, honestly, June, thought Emily crossly, you aren't being any fun at all. June was right, of course, but it would be fun to think for a little while that there was a ghost walking across the roof of a thirteen-room house, especially when Daddy was still uptown at band practice. It would be pleasantly scary if the pioneer ancestors had left a ghost or two around the house, perhaps in the cupola, but these ancestors must have been too busy clearing the land and settling the state of Oregon to participate in any ghostly activities like people in some of the sad old songs Mama sometimes sang. As far as Emily knew, there was not a brokenhearted damsel or a disappointed lover killed in a duel in the lot. They did get pretty hungry toward the end of their journey across the plains to Oregon, but nobody languished or wasted

away. Apparently they ate a good square meal when they got to Oregon and went right to work cutting trees, pulling stumps, and planting crops. June was right. The house, even if it did have thirteen rooms, was not the least bit haunted.

Emily tried to think of something ghostly, but all she could think of was the skeleton of a cow down in the pasture and there was nothing ghostly about that. The cow did not die of a broken heart. It was a cow Daddy had to shoot because it ate some baling wire. It had been one of Daddy's best milkers and it was a shame that a cow that gave milk so rich in butterfat had to go eat baling wire.

And then Plince howled. It was a long-drawn-out, dismal, unearthly howl that began low in the scale and rose to a high, eerie note.

Each girl caught her breath. “June,” whispered Emily, “do you know what that means?

When a dog howls it means somebody is going to

die!

”

This time June did not sound so matter-of-fact. “He's probably howling at the moon.”

“There isn't any moon,” said Emily, realizing for the first time that sometime during the evening the sky had clouded over. “It is a dark and cloudy night.”

The girls huddled closer together in bed. Somewhere a loose shutter banged as persistently as if someone were trying to get in. Emily remembered a snatch of Mama's spooky poem about someone “rapping, rapping at my chamber door.” Her heart pounded like the dasher of a churn.

Plince's howl rose and fell again in a way that made the girls shiver. The snap of the floor in the bedroom made them both start. They giggled nervously and lay still and tense. Plince's howl died and the night seemed unnaturally silentâas if it were waiting for something.