Elizabeth's Spymaster (18 page)

Read Elizabeth's Spymaster Online

Authors: Robert Hutchinson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Ireland

Gifford, described as ‘yormg and without any beard’, was immediately stopped at Rye, arrested and sent to London, escorted by Richard Daniel, one of the port searchers. He met Walsingham at Greenwich Palace and lodged for a time with Thomas Phelippes so that he could be kept under close surveillance. After a number of interviews with the grim-faced Minister, it did not take much to subvert him. Gifford agreed that in return for suitable remuneration, all Mary’s secret letters and those she received would pass through the spy master’s hands. With £20 of Walsingham’s secret service funds in his purse, he was sent to see Châteauneuf, who appointed one of his secretaries, Cordaillot, to handle the Scottish queen’s correspondence.

All that now remained was to arrange for a method of getting the correspondence in and out of Chartley that would not arouse the suspicions of Mary or her household there. Walsingham dispatched Phelippes to Staffordshire to find a suitable covert means.

Phelippes spent four or five days at the manor house and met Mary there. She apparently sounded him out on his susceptibility to bribery, which must have caused him some amusement but at least indicated that she did not harbour any suspicions about his presence. After some investigation, the method of communication was fixed. The household received their supplies of beer from a brewer in the nearby town of Burton, delivered once a week to Chartley in small wooden casks or kegs. It was decided that the secret letters would be held in a waterproof wooden canister small enough to slip into the keg via the hole used for its bung. The brewer – referred to as ‘the honest man’ by Paulet – was told to transport the letters by this method and when the process was reversed, to hand over Mary’s letters to Gifford.

The plan was swiftly put into operation and on the evening of 16 January 1586, the Scottish queen was delighted to receive her first secret message for almost a year. Ironically, it was a letter from Morgan in Paris, recommending the services of Gilbert Gifford. She immediately dashed off a reply, which spoke of her concern for her new messenger’s safety: ‘I fear his danger of sudden discovery, my keeper [Paulet] having settled

such an exact and rigorous order in all places.’

21

This letter quickly found its way to Walsingham, who handed it over to Phelippes for deciphering and copying and then to Arthur Gregory for resealing. It was conveyed to the French ambassador and eventually reached Morgan on 15 March. The system had worked and both sides were delighted by its success – but for very different reasons.

The next few weeks were occupied with Mary dictating letters to catch up on the long gap in her correspondence. They were duly inserted into the empty beer keg and Gifford handed them over to Paulet late on 5 February. Mary’s custodian wrote to Walsingham:

[Gifford] desired that these packets might be sent to you with speed and that his father might be advised by Mr Phelippes to call him to London as soon as … possible, to the end that he might deliver these letters to the French ambassador in convenient time for the better conservation of his credit that way.

The suspicious Paulet retained doubts about the honesty and loyalty of Gifford: ‘I will hope the best of your friend but I may not hide from you that he doubled in his speech [contradicted himself] once or twice …’

22

He also had fears about the Burton brewer: ‘God knows if under the cloak of this trifle, greater treacheries may be contrived.’

Mary’s correspondence included letters to the Duke of Guise, the Archbishop of Glasgow and another to Morgan. Again they were intercepted, decoded, resealed and delivered to Châteauneuf on 19 February. The French envoy then handed over all the secret letters that had been held for her for so long in the embassy. Gifford immediately delivered them to Phelippes, who reported to Walsingham:

The party [Gifford] has brought one and twenty packets great and small but not so soon as I looked for and himself thought. I find them of very old dates, which I impute, considering the number also, to the stay of intelligence …

23

Phelippes also returned one ‘alphabet’ – the key to a cipher – that he had taken away by mistake. Although now very dated, the letters – from

Morgan, the Catholic fugitive Charles Paget, Father Persons, Sir Francis Englefield in Spain, Mendoza in Paris and from the Duke of Guise and the Prince of Parma – must have been an intelligence treasure trove to Walsingham and read eagerly by him. Gifford departed for France in April and a substitute messenger was found, one Thomas Barnes. The packets from the embassy were too bulky to squeeze through the bung hole of the beer cask, so the pages were divided up into smaller rolls, which at least removed the need for Gregory to reseal them. Such a huge volume of correspondence must have taken both Phelippes and Gilbert Curie, one of Mary’s confidential secretaries, much time to decode and transcribe.

A number of types of cryptography were used by both Mary and Walsingham in their letters. In the National Archives at the Public Record Office at Kew in Surrey are preserved two small blue leather folio volumes of ciphers and decodes used by Walsingham in the final entrapment of Mary Queen of Scots.

24

The first volume alone contains fifty-five separate codes, or alphabets, some later seized by Paulet in his search of her rooms at Chartley. All are simple substitution ciphers: using a mix of numbers, letters and symbols as substitutes for names, places and words in English or in French.

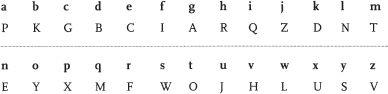

In its least sophisticated form, both receiver and sender would have a copy of the cipher to decode messages. The more frequently such codes are changed, the greater the security of the messages. Hence, today, ‘onetime-only’ ciphers pose real problems for those attempting to crack them. Here is an example of a simple substitution cipher of the type used in the late sixteenth century:

Thus, the coded message TPFS FCWGJCB YE TYEBPS could be read off the cipher as ‘Mary rescued on Monday’. To disguise the message further, the words would be run together with the breaks between

them removed to avoid offering up clues from the use of short words containing vowels.

In the code used by Gilbert Gifford and Mary at Chartley, the symbols ‘#’, ‘X/’, ‘V and ‘Z’ represent the king of France, the king of Spain, Elizabeth and Mary herself, respectively.

25

In another code, ‘X.’ represents the Pope; ‘0’ the word ‘intelligence’; ‘8’, packet; ‘y’, letter; ‘e’, secret; and’_’, Francis Walsingham.

26

Interestingly, a very similar cipher system was used in mobile telephone text messages by al Qaeda agents in Pakistan in 2005 to disguise rendezvous locations and individuals’ identities.

The use of ciphers and the methods employed to decode them had come to the attention of Burghley in the 1560s when the mathematician, astrologer and magician John Dee returned to England with a copy of a book entitled

Stenographia,

written by Trithemius, Abbot of Spandheim, in the late fifteenth century. Dee adapted the ideas in the book and made them available to Walsingham, who visited him several times from January 1583 and with whom he was an irregular correspondent.

27

Deciphering substitution codes is based on the frequency of use of letters of the alphabet. This method had been known for a long time, using techniques evolved by the ninth-century Arab codebreaker al-Kindi. In English, the letter ‘e’ accounts for thirteen per cent of all letters used in any kind of prose – whereas ‘z’ is used less than one per cent of the time. Whatever letter, number or symbol is substituted, it retains its original frequency of use. Thus by analysing the frequency of the different letters used in a code, it is possible to work out which consonant or vowel each substituted letter represents. However, in the sixteenth century, to confuse and complicate the work of the decipherer, some codes included ‘nulls’ – letters that were fakes and represented nothing, or, as Thomas Phelippes sometimes noted, ‘doubles the precedent’ – thereby changing the rules of the code. Naturally, the work is made immeasurably easier if a copy of the cipher falls into the decipherer’s hands – which Mary fatally facilitated in March 1586 when she sent a new code to Châteauneuf, which was intercepted and copied by Walsingham.

The key figure in all this movement of secret correspondence to and from Chartley was, of course, the brewer in Burton. Without his

cooperation, the whole elaborate scheme would have collapsed. Although he was reputedly a good Catholic, he was not ashamed to receive bountiful bribes from both Walsingham and Mary Queen of Scots. With an eye on market forces, he also put up the price of his beer, comfortable in the knowledge that Paulet could not now go elsewhere for his supplies of ale. Gifford in turn extorted money from Morgan by pretending that he was paying the brewer.

28

Paulet was disgusted.

The ‘honest man’ plays the harlot with this people egregiously, preferring his particular profit and commodity before their service … The house where he dwells is distant from here only ten miles and yet, I do not remember that he has delivered at any time any packet to this queen until six or seven days after the receipt …

He appoints all places of meeting at his pleasure, wherein he must be obeyed, and has no other respect that he may not ride out of his way, or at the least, that his travel for his cause may not hinder his own particular business.

29

Regardless of these various machinations, Walsingham’s trap had been baited: he only needed to wait for the jaws to snap shut upon Mary.

The genesis of that much-sought evidence lay in the person of John Ballard, who had been ordained priest at Châlons in France on 4 March 1581 and secretly entered England later that month. He was quickly arrested and imprisoned in the Gatehouse Jail at Westminster, where he met another priest called Anthony Tyrrell. They both escaped and left the country, returning on Boxing Day 1584 at Southampton. Sometime during Lent in 1586, Ballard had supper at the Plough Inn, just outside Temple Bar on the western fringe of the City of London. Present were a number of young Catholic gentlemen, including one Anthony Babington and Bernard Maude.

Babington, twenty-five years old and married with a young daughter,

30

had been a page to the Earl of Shrewsbury when he was Mary’s keeper in 1579. He had delivered five packets of letters to the Scottish queen during 1583-4 and had then ducked out of this dangerous duty. The Jesuit Father William Weston described him as ‘attractive in face and form, quick of

intelligence, agreeable and facetious’.

31

But he was inexperienced in the ways of the world and an unlikely man of action.

Maude was formerly a member of the household of Edwin Sandys, the Archbishop of York, and had falsely accused the prelate of religious unorthodoxy. Sandys had handed over cash to Maude and his friends in an optimistic attempt to keep them quiet. But Maude’s sins had found him out and he was forced to repay the archbishop the money, as well as a £300 ‘fine’ to the queen, and served three years in the Fleet Prison in London for his blackmail. If he had not confessed, ‘his ears would have been slit’ as a common offender.

32

He was another miscreant who had been freed early in return for agreeing to undertake clandestine work for Elizabeth’s government. As Maude sat, laughing and joking with his Catholic colleagues over their wine and ale in the Plough, they did not guess that he was another of Walsingham’s spies.

Ballard was completely taken in. He travelled to Rouen with Maude in May and on to Paris where he met Charles Paget, leader of the English Catholic laity in the French capital. There, Ballard told his receptive audience that the Catholic population of England were willing to take up arms against Elizabeth and that this was an opportune time, as most of the best Protestant military leaders and soldiers were away fighting in the Low Countries with Leicester’s expeditionary force. An excited Paget took Ballard to Mendoza, the Spanish ambassador in Paris, and he repeated his views. Paget told Mary in a letter dated 19 May 1586 (and later read by Walsingham):

[Mendoza] heard him very well and made him set down in number how many in every shire would be contented to take arms and what number of men armed and unarmed they could provide … He likewise gave him information of the ports with many other things fit to be known.

33

All this must have been drearily familiar to the canny Mendoza: the eternal mirage of an English Catholic uprising, merely requiring a foreign invasion to ensure a total victory over the heretic forces of Protestantism. He and the Spanish government had heard it all before: more wishful

thinking than the hard reality of military capability. But this time there was more, which must have made the Spanish envoy prick up his ears. Afterwards, he carefully wrote out an account for King Philip II in Madrid and encoded the dispatch himself: