Elizabeth the Queen (43 page)

Read Elizabeth the Queen Online

Authors: Sally Bedell Smith

In several of her Christmas broadcasts after Bloody Sunday, the Queen had touched on what she called “our own particular sorrows in Northern Ireland,” extending prayers and sympathy to those who were suffering, and encouraging Protestants and Catholics working together for peace “to keep humanity and common sense alive.” She predictably bridled when officials had second thoughts in the summer of 1977 about her planned trip to Northern Ireland, just as she had resisted in 1961 when her trip to Ghana was nearly canceled. “Martin, we

said

we’re going to Ulster,” she told her private secretary. “It would be a great pity not to.”

On August 10, she landed on the grounds of Hillsborough Castle outside Belfast by helicopter—judged by her security advisers to be “the safest way for the Queen to travel.” It was her first trip on a helicopter, a means of transportation that had long made her nervous, despite her usual physical courage.

She was protected by extraordinary security during her two days in Ulster, with some 32,000 troops and police on alert. About seven thousand people were invited to her receptions, garden party, and investiture, all of which were broadcast on television. After visiting the New University of Ulster at Coleraine, she joined her family on

Britannia

for their annual Western Isles cruise and a two-month retreat at Balmoral. Her trip to Northern Ireland, she said in that year’s Christmas broadcast, reminded her that “nowhere is reconciliation more desperately needed.” Her ability to travel there allowed “people of goodwill” to be “greatly heartened by the chance they had to share the celebrations.”

The second Commonwealth tour took her to Canada and the Caribbean for nearly three weeks. She returned from Barbados on November 2 by Concorde, the distinctive beak-nosed supersonic jetliner that had gone into service in January 1976. Her three-hour-and-forty-five-minute trip gave a futuristic flourish to the end of her 56,000 miles of jubilee travels.

On November 15 at 10:46

A.M.

, she became a grandmother at age fifty-one with the arrival of Anne’s first child, Peter Phillips. He was the first baby in the royal family to be born a commoner in five hundred years, since Mark Phillips had declined to take a title when he married Anne. They intended to raise their son—and his sister, Zara, born four years later—apart from the pressures of royal obligations, a decision that both children later welcomed.

That month Martin Charteris retired at age sixty-four after twenty-seven years of serving the Queen. Aside from Bobo MacDonald, no one in the royal household knew her better, had worked more intimately with her, or had seen her through so many stages of her life, from her formative years as a working princess through her grief over her father’s early death to her evolution as a confident and capable sovereign. He had in every respect lightened her load, not only with his keen judgment but with the verve he brought to her speeches and his gentle prodding to open her mind to new approaches.

They said farewell at a brief audience in Buckingham Palace. To help keep her emotions in check, Elizabeth II brought along her flinty daughter, who wouldn’t tolerate tears from her mother. “The Queen knew Martin would cry, and he did,” said Gay Charteris. “He was not inhibited by his emotions. She didn’t cry, and in her view, the least said, the better.” Some years later, Elizabeth II confided to her mother that when “my Martin” left, she missed him but she knew “he was still around if I needed to ask anything difficult.” All she said that morning at the Palace was, “Martin, thank you for a lifetime,” as she presented him with a silver tray inscribed with the same sentiment. When his tears abated, he mustered his customary levity. “The next time you see this,” he said. “It will have a gin and tonic on it.”

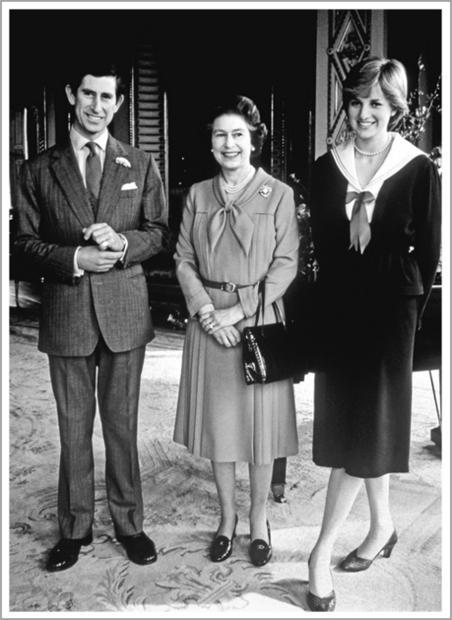

The Queen was always kind to

Diana. But even after she had spent

time in her mother-in-law’s company,

Diana remained “terrified of her.”

Prince Charles and his future wife Lady Diana Spencer with the Queen shortly after the announcement of the couple’s engagement, March 1981.

Press Associarìon Images

THIRTEEN

Iron Lady and English Rose

Iron Lady and English Rose

T

HE

Q

UEEN’S

S

ILVER

J

UBILEE SUCCEEDED IN LIFTING THE NATION’S

spirits during a troubled time, much as her wedding had done during the postwar gloom. Prime Minister James Callaghan had been struggling to jump-start Britain’s stagnant economy from the moment of his election at age sixty-four in 1976. That year his government was forced to stave off bankruptcy with a loan of $3.9 billion from the International Monetary Fund. The money came with the sort of conditions—curbs on government spending and wage increases in the public sector—that were customarily imposed on developing countries.

The prime minister—nicknamed “Sunny Jim”—was an avuncular presence in his weekly meetings with the Queen, who was fourteen years his junior. The son of a chief petty officer in the Royal Navy and a schoolteacher, he had entered the civil service as a tax collector when he was unable to afford a university education. An unabashed monarchist, he enjoyed his meetings with the Queen, relieved to be in a setting where “conversation flowed easily and could roam anywhere over a wide range of social as well as political and international topics.” After spending fifteen minutes or so on three prearranged agenda items, their talk over the next hour might touch on their families or perhaps the price of hay in Sussex, where he had a farm, compared to Norfolk or Scotland. Callaghan learned to respond adroitly to the Queen’s fascination with political personalities, and he came to admire her oblique way of getting across her points: how she “weighs up” the problems of her prime minister, hinting at her thoughts in a “pretty detached” manner, and avoiding direct advice.

At six foot one, he was the tallest of the Queen’s prime ministers, handsome, easygoing, ready with compliments and even mildly flirtatious. One week she memorably took him for a stroll in the Buckingham Palace gardens and coquettishly placed a sprig of lily of the valley in his buttonhole. Callaghan correctly summarized her evenhanded approach to all her prime ministers, with the exception of Winston Churchill, who was sui generis. “What one gets,” Callaghan said, “is friendliness but not friendship.”

For “poor old Jim Callaghan,” as the Queen Mother referred to him, the Tuesday evening interludes offered a brief moment of tranquillity amid political strife. Despite the compelling need for austerity, the unions plunged ahead in 1978 with demands for fat wage increases, which meant higher government spending to placate public employees. Throughout what became known as the “Winter of Discontent”—one of the coldest on record—the country was crippled by a series of strikes by truck drivers, hospital orderlies, trash collectors, ambulance drivers, school janitors, and gravediggers. Piles of refuse filled the streets, a symbol of a nation that had lost its way.

On March 28, 1979, the Conservatives in the House of Commons introduced a vote of no confidence in the government, which is required under the constitution to have the support of a majority of the legislature. The Labour government lost the confidence motion by one vote (thanks mainly to the Liberal Party’s backing of the Tory initiative), and a general election was called for May 3. The Conservative Party, led by fifty-three-year-old Margaret Thatcher, swept to power, winning 339 seats to 268 for Labour and 11 for Liberals. Thatcher’s arrival at Buckingham Palace the next day to kiss hands as the first female prime minister was a historic moment for the ambitious young politician who had written twenty-seven years earlier that the accession of Elizabeth II could help remove “the last shreds of prejudice against women aspiring to the highest places.” When thoroughbred trainer Ian Balding called the Queen shortly afterward, she said, “What do you think about Margaret Thatcher getting in?” “Ma’am,” he replied, “I’m not sure I can get my head around a woman running the country.” The Queen fell silent. “You know what I mean?” he said. This time she laughed, and said nothing in reply.

The two women were only six months apart in age. Impeccably dressed and meticulously coiffed, they were equally professional and hardworking, but they differed markedly in background and temperament. Margaret Roberts was the daughter of a successful grocer in Grantham, Linconshire, who lived above the store. She earned her Oxford degree in chemistry on a scholarship, married Denis Thatcher, a prosperous divorced businessman, and worked as a lawyer before being elected to Parliament in 1959.

She oversaw housing and education policy for the various Conservative prime ministers, and in 1975 the party elected her as its leader, deposing Edward Heath. She was determined to reverse the country’s economic decline by loosening the grip of organized labor, dramatically cutting public spending, reducing the dependence of citizens on their government, deregulating business to promote growth, and, along the way, raising Britain’s stature on the world stage.

Thatcher was fearless and nimble in debate, and passionate about her principles of bedrock conservatism shaped by such intellectuals as Milton Friedman and Friedrich von Hayek. The conservative historian Paul Johnson admiringly called her “the eternal scholarship girl. She loved learning, swotting things up, being tested, passing with honours.” Her zest for combat was antithetical to the Queen’s nonconfrontational nature. Nor could the Queen share with her prime minister something like the irony of her conversation with Ian Balding, because Thatcher’s sense of humor was barely discernible. For the next eleven years, there would be none of the lively banter that Elizabeth II enjoyed with James Callaghan, whatever she might have thought of his policies. Conversations would no longer be divided equally, since Thatcher had a habit of lecturing. “The Queen found that irritating,” said a top army general close to Elizabeth II.

Their audiences were formal and businesslike. “The agenda included major topical events,” said Charles Powell, who was the prime minister’s senior foreign policy adviser. “It was not a trivial agenda. Lady Thatcher wouldn’t prepare. She would be fully up to speed anyway. She would want to know what the Queen would want to talk about, and what she might say to the Queen, who was working on the same information base. Lady Thatcher didn’t need anything to impose discipline, because she was disciplined enough.”

Afterward, the prime minister would join the Queen’s private secretaries for a whisky. “She chatted with us,” said a former courtier. “She was quite relaxed, which was rare for her. I think the audience was something like a tranquilizer.” On returning to Downing Street, Thatcher might carry a request from the Queen, usually something to do with an army regiment. “She seemed to come back in a cheerful frame of mind,” recalled Charles Powell. “She genuinely enjoyed the meetings. Her demeanor on returning did not say, ‘Oh God, what a waste of time that was.’ In fact it was the opposite.”

After giving birth in 1953 to twins, Thatcher, like the Queen, had been an exception in her generation as a working mother, and had likewise relied on nannies for her children’s upbringing. Both women had trouble discussing their feelings, which prevented them from venturing into personal topics that might have formed a bond—the push and pull of combining professional life and motherhood, and the challenges of having a husband in a subordinate position. One exception was the time the Queen ended an audience by offering wardrobe tips before the prime minister visited Saudi Arabia. Otherwise, the two women avoided any hint of “girl talk.” “Mrs. Thatcher would have thought it impudent to have tried to establish a close relationship and would have expected the Queen to make the first move,” said a former government adviser. Although no such move was forthcoming, the Queen treated her prime minister with courtesy and thoughtfulness. Whenever the Thatchers came to Windsor for a dine-and-sleep, Elizabeth II took care to choose items for the library exhibit with particular meaning: one year a selection of antique fans, another time a manuscript written by Mozart when he was ten years old.