Eldritch Tales (49 page)

Authors: H.P. Lovecraft

T

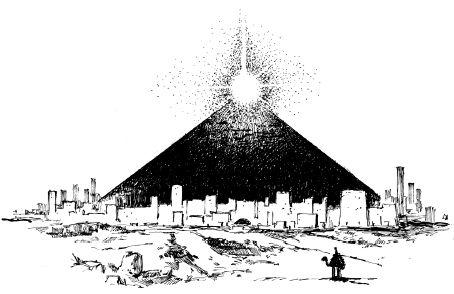

HEY CUT IT DOWN, and where the pitch-black aisles

Of forest night had hid eternal things,

They scal’d the sky with tow’rs and marble piles

To make a city for their revellings.

White and amazing to the lands around

That wondrous wealth of domes and turrets rose;

Crystal and ivory, sublimely crown’d

With pinnacles that bore unmelting snows.

And through its halls the pipe and sistrum rang,

While wine and riot brought their scarlet stains;

Never a voice of elder marvels sang,

Nor any eye call’d up the hills and plains.

Thus down the years, till on one purple night

A drunken minstrel in his careless verse

Spoke the vile words that should not see the light,

And stirr’d the shadows of an ancient curse.

Forests may fall, but not the dusk they shield;

So on the spot where that proud city stood,

The shuddering dawn no single stone reveal’d,

But fled the blackness of a primal wood.

THE ANCIENT TRACK

T

HERE WAS NO HAND to hold me back

That night I found the ancient track

Over the hill, and strained to see

The fields that teased my memory.

This tree, that wall – I knew them well,

And all the roofs and orchards fell

Familiarly upon my mind

As from a past not far behind.

I knew what shadows would be cast

When the late moon came up at last

From back of Zaman’s Hill, and how

The vale would shine three hours from now.

And when the path grew steep and high,

And seemed to end against the sky,

I had no fear of what might rest

Beyond that silhouetted crest.

Straight on I walked, while all the night

Grew pale with phosphorescent light,

And wall and farmhouse gable glowed

Unearthly by the climbing road.

There was the milestone that I knew—

‘Two miles to Dunwich’ – now the view

Of distant spire and roofs would dawn

With ten more upward paces gone . . .

There was no hand to hold me back

That night I found the ancient track,

And reached the crest to see outspread

A valley of the lost and dead:

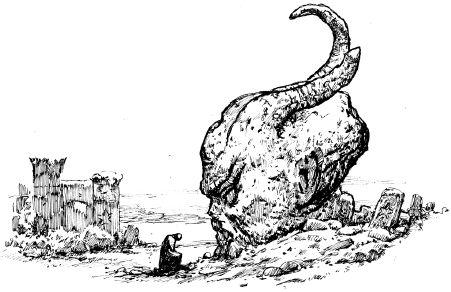

And over Zaman’s Hill the horn

Of a malignant moon was born,

To light the weeds and vines that grew

On ruined walls I never knew.

The fox-fire glowed in field and bog,

And unknown waters spewed a fog

Whose curling talons mocked the thought

That I had ever known this spot.

Too well I saw from the mad scene

That my loved past had never been—

Nor was I now upon the trail

Descending to that long-dead vale.

Around was fog – ahead, the spray

Of star-streams in the Milky Way . . .

There was no hand to hold me back

That night I found the ancient track.

THE ELECTRIC EXECUTIONER

(

with Adolphe de Castro

)

F

OR ONE WHO HAS NEVER faced the danger of legal execution, I have a rather queer horror of the electric chair as a subject. Indeed, I think the topic gives me more of a shudder than it gives many a man who has been on trial for his life. The reason is that I associate the thing with an incident of forty years ago – a very strange incident which brought me close to the edge of the unknown’s black abyss.

In 1889 I was an auditor and investigator connected with the Tlaxcala Mining Company of San Francisco, which operated several small silver and copper properties in the San Mateo Mountains in Mexico. There had been some trouble at Mine No. 3, which had a surly, furtive assistant superintendent named Arthur Feldon; and on August 6th the firm received a telegram saying that Feldon had decamped, taking with him all the stock records, securities, and private papers, and leaving the whole clerical and financial situation in dire confusion.

This development was a severe blow to the company, and late in the afternoon President McComb called me into his office to give orders for the recovery of the papers at any cost. There were, he knew, grave drawbacks. I had never seen Feldon, and there were only very indifferent photographs to go by. Moreover, my own wedding was set for Thursday of the following week – only nine days ahead – so that I was naturally not eager to be hurried off to Mexico on a man-hunt of indefinite length. The need, however, was so great that McComb felt justified in asking me to go at once; and I for my part decided that the effect on my status with the company would make ready acquiescence eminently worth while.

I was to start that night, using the president’s private car as far as Mexico City, after which I would have to take a narrow-gauge railway to the mines. Jackson, the superintendent of No. 3, would give me all details and any possible clues upon my arrival; and then the search would begin in earnest – through the mountains, down to the coast, or among the byways of Mexico City, as the case might be. I set out with a grim determination to get the matter done – and successfully done – as swiftly as possible; and tempered my discontent with pictures of an early return with papers and culprit, and of a wedding which would be almost a triumphal ceremony.

Having notified my family, fiancée, and principal friends, and made hasty preparations for the trip, I met President McComb at eight p.m. at the Southern Pacific depot, received from him some written instructions and a check-book, and left in his car attached to the 8:15 eastbound transcontinental train. The journey that followed seemed destined for uneventfulness, and after a good night’s sleep I revelled in the ease of the private car so thoughtfully assigned me; reading my instructions with care, and formulating plans for the capture of Feldon and the recovery of the documents. I knew the Tlaxcala country quite well – probably much better than the missing man – hence had a certain amount of advantage in my search unless he had already used the railway.

According to the instructions, Feldon had been a subject of worry to Superintendent Jackson for some time; acting secretively, and working unaccountably in the company’s laboratory at odd hours. That he was implicated with a Mexican boss and several peons in some thefts of ore was strongly suspected; but though the natives had been discharged, there was not enough evidence to warrant any positive step regarding the subtle official. Indeed, despite his furtiveness, there seemed to be more of defiance than of guilt in the man’s bearing. He wore a chip on his shoulder, and talked as if the company were cheating him instead of his cheating the company. The obvious surveillance of his colleagues, Jackson wrote, appeared to irritate him increasingly; and now he had gone with everything of importance in the office. Of his possible whereabouts no guess could be made; though Jackson’s final telegram suggested the wild slopes of the Sierra de Malinche, that tall, myth-surrounded peak with the corpse-shaped silhouette, from whose neighbourhood the thieving natives were said to have come.

At El Paso, which we reached at two a.m. of the night following our start, my private car was detached from the transcontinental train and joined to an engine specially ordered by telegraph to take it southward to Mexico City. I continued to drowse till dawn, and all the next day grew bored on the flat, desert Chihuahua landscape. The crew had told me we were due in Mexico City at noon Friday, but I soon saw that countless delays were wasting precious hours. There were waits on sidings all along the single-tracked route, and now and then a hot-box or other difficulty would further complicate the schedule.

At Torreón we were six hours late, and it was almost eight o’clock on Friday evening – fully twelve hours behind schedule – when the conductor consented to do some speeding in an effort to make up time. My nerves were on edge, and I could do nothing but pace the car in desperation. In the end I found that the speeding had been purchased at a high cost indeed, for within a half-hour the symptoms of a hot-box had developed in my car itself; so that after a maddening wait the crew decided that all the bearings would have to be overhauled after a quarter-speed limp ahead to the next station with shops – the factory town of Querétaro. This was the last straw, and I almost stamped like a child. Actually I sometimes caught myself pushing at my chair-arm as if trying to urge the train forward at a less snail-like pace.

It was almost ten in the evening when we drew into Querétaro, and I spent a fretful hour on the station platform while my car was sidetracked and tinkered at by a dozen native mechanics. At last they told me the job was too much for them, since the forward truck needed new parts which could not be obtained nearer than Mexico City. Everything indeed seemed against me, and I gritted my teeth when I thought of Feldon getting farther and farther away – perhaps to the easy cover of Vera Cruz with its shipping or Mexico City with its varied rail facilities – while fresh delays kept me tied and helpless. Of course Jackson had notified the police in all the cities around, but I knew with sorrow what their efficiency amounted to.

The best I could do, I soon found out, was to take the regular night express for Mexico City, which ran from Aguas Calientes and made a five-minute stop at Querétaro. It would be along at one a.m. if on time, and was due in Mexico City at five o’clock Saturday morning. When I purchased my ticket I found that the train would be made up of European compartment carriages instead of long American cars with rows of two-seat chairs. These had been much used in the early days of Mexican railroading, owing to the European construction interests back of the first lines; and in 1889 the Mexican Central was still running a fair number of them on its shorter trips. Ordinarily I prefer the American coaches, since I hate to have people facing me; but for this once I was glad of the foreign carriage. At such a time of night I stood a good chance of having a whole compartment to myself, and in my tired, nervously hypersensitive state I welcomed the solitude – as well as the comfortably upholstered seat with soft arm-rests and head-cushion, running the whole width of the vehicle. I bought a first-class ticket, obtained my valise from the sidetracked private car, telegraphed both President McComb and Jackson of what had happened, and settled down in the station to wait for the night express as patiently as my strained nerves would let me.