Edie (42 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

Edie was not the kind of person you could leave sitting in the corner of a room reading a book by herself. There was no peace to be had. We’d cackle about the night before. Most of the day was taken up with talking to Andy on the phone, both of us. Andy was a real blabber

mouth on the phone. He carried on. He told you every little thing he did from the second he woke up. He would compose exercises with Edie. Andy did one hundred pull-ups a morning—which does not surprise me because he had an incredibly strong back.

Then there were calls; interviews. People were interested at that point. Men from the night before she’d given her name to. She never would go out with anybody but Andy at night. So it was funny listening to her get out of these entanglements. She’d claim to be busy; she’d say she had to go to the Factory and shoot a scene. She kept turning to me: “How do I get out of this?” That was very sweet.

We really did not do much during the day. Edie would spend hours doing her face. She did it very well, because she could go out for twelve hours, leaving in the afternoon and not returning until the next dawn, a hundred parties in between, and her make-up would never budge. Absolutely flawless. I remember waiting two hours for her to get out of the bathroom. I didn’t want to disturb the star putting on her face. There were a few unspoken rules, and that was one of them. The last thing that went on was the gold glitter. Gold dust. She loved the way it glittered. She would come in and say, “Let me give you some of this,” and she’d put it all over my cheeks. “Isn’t it terrific?” In the late afternoon we would leave for the Factory. It was always very busy there. Then we would go to the parties at night.

BOB NEUWIRTH

The great hangout in the city was Max’s Kansas City. It was at a strange location—Park Avenue South and Seventeenth Street—for a kind of artists’ restaurant. The guy who owned it had been a manager of a steakhouse downtown. He picked the location so you wouldn’t get mugged, but he opened it with an eye for a clientele of painters and writers from downtown. During the Pop Sixties it became a famous place to hang out. As soon as it became public knowledge, there was a lot of business. But it was terrific because people in coats and ties would be kept waiting out on the sidewalk while artists and scroungy people were given tables immediately. It was part of the whole appeal of the place. The back room became a base for Andy.

A close friend brought Bobby Kennedy to Max’s to meet Edie. Bobby only stayed a few minutes because his bodyguard ordered him out of there. He had smelled something mysterious in the air. Bobby was having a good time. He was ready to boogie. BI’ll Barry, his bodyguard, suddenly said, “Senator, we must leave.” Bobby looked surprised and

a little annoyed. “But I’ve just ordered a drink,” he said. BI’ll Barry’s voice hardened and became urgent. “Senator, we must get out of here at once,” and he whisked Bobby out of Max’s. Apparently he had smelled marijuana. We sat there astonished. It all seemed ridiculous.

HELEN HARRINGTON

You remember the lady who killed herself—Andrea Feldman? loved to take her blouse off in Max’s kansas city all the time. She took her shirt off so often to show her tits that the people sitting around Max’s would say: “Oh, not your tits

again!

One night Jane Fonda was sitting in the back room and here came Andrea hopping across the tables with her shirt off . . . Everyone calling out, “Booooo!” they’d seen them so often. Eric Emerson was always taking his pants down and showing his ass and his cock, with again everyone saying, “Ughh, must we see

that

again?!” I liked Eric. He didn’t quite know what to do. He was one of the creatures that made the atmosphere there sort of special. He got more bonkers as the years progressed. You’d see him and he’d be drinking a glass of piss I He finally OD’d.

VIVA

like many of the people who hung out at Max’s, Andrea Feldman had no money and no place to live, even when she had a leading role in a warhol film. She finally demanded money and said that Andy gave her some cheap bracelets instead . . . when she threw them on the floor, somebody beat her up. Next thing I heard she was in a mental institution. Next thing I knew Andrea had jumped out the fourteenth-floor window of her uncle’s apartment, clutching a bible and a crucifix. She left behind a number of suicide notes, several addressed to Andy. The only phrase that escaped censoring was, “Goodbye, I’m going for the big time.”

PAUL ROTHCHILD

The back room at Max’s was pure theater. People dressed for it. Those red fluorescent lights. The first really broad expression of frank homosexuality in New York City I saw there at Max’s—embracing, kissing, great jealousies displayed for the world to see. Before, it had been a confused, almost proper, European kind of homosexuality, but with the Warhol wave it became very theatrical, direct, and out front. Then at the tables you saw the seedier side—people shooting up coke, speedballs, the great pI’ll contest: “How many could you drop at Max’s and stI’ll walk out?” Though I never saw Edie shoot up there, she was one of the queens of Max’s. No question about it. She evoked a kind of warmth. Everybody felt very tender toward her . . . protective and cozying her.

Andrea Feldman

TERRY SOUTHERN

If you wanted to describe the back room of max’s in a, god forbid, negative way, you’d use words like “Desperation” or “Hysteria”—that sort of thing. Going the positive route, of course, you’d talk about “Sensitive,” “Intense,” or just plain “Hilarious.” It was like a carnivorous arena. There was always this buzz along the Rialto: “Andy’s coming! Andy’s coming!” . . . all on this weird level of “Maybe 111 catch Andy’s eye and hell make this ultimate film or painting of me . . . I’ll be the next Edie or the next Baby Jane.”

There was a moment, a brief, flaring instant when Edie was like really the tops. She would walk in the back room of Max’s Kansas City and everybody would whisper: “Here comes Edie.” Fuck fantastic. Much more important in her head than winning some dumb-dumb award like the Oscar.

SANDY KIRKLAND

There were problems. The others would turn off Edie and not give her the attention she needed. Part of her understood, but she was stI’ll very hurt by it. I can see her in my mind’s eye at the back of the Factory, where there was a bathroom, back there alone, abandoned, and she’d be dancing around, spaced out, weird.

HENRY GELDZAHLER

I suppose Edie thought of herself as a caterpillar that had turned into a butterfly. She had thought of herself as just another kid in a big, rather unhappy family, and all of a sudden the spotlights were on her and she was being treated as something very, very special, but inside she felt like a lump of dirt. Then when she was being paid less attention to, she didn’t know who she was. That possibility of destruction was built into the weakness of her personality. We have to get used to the reality that we’re alone. If you can’t get used to it, then you go mad. And she went kind of mad.

I came to her apartment a couple of times, which I thought very grim. It was very dark, and the talk was always about how hungover she was, or how high she was yesterday, or how high she would be tomorrow. She was very nervous, very fragile, very thin, very hysterical. You could hear her screaming even when she wasn’t screaming—this sort of supersonic whistling.

GERARD MALANGA

The first hints of the split between Andy and Edie came with the making of the film

My Hustler

in July, 1965. Chuck Wein conceived of this film for Andy. He didn’t write anything in it for Edie—not surprising since it was a homosexual film—but he did include a brief sequence with Genevieve Charbin. I don’t know what Chuck’s motives were, but Edie complained.

DANNY FIELDS

She wanted to move on. She was as great in the little movies made in the Factory as anyone was in a four-million-dollar movie from MGM. So Edie used to wonder: “Should I go to Hollywood? Should I break away from Andy? Should I get a real agent?” People were toying around with her. All sorts of leads. But she’d meet them and come back and say, “Oh, God, they’re such assholes! I can’t work with them. I have to be with my friends. I want to be with people I love. I could never love those people. They’re all stupid. Morons. Forget it.”

That’s not your most professional of attitudes. I’d say to Edie: “You

have

to do it. If you want to make it in show business, you have to deal with morons. It doesn’t matter if they don’t like you for exactly the right reasons, or pamper you the right way, or are too stupid to appreciate you for what you really are.”

But it was hard to get away from the Andy thing. It was so much fun; it was party time. She felt she couldn’t make the transition into the real crap you have to deal with in order to make it.

Once you were in those silver aluminum rooms in the Factory, you were in the world . . . Like going through the looking glass in a way . . . a point of contact where everything is happening and one is recognized and creative.

RONALD TAVEL

Edie started to annoy me when she asked what the scripts were about. I’d say to her, It’s not your business. Besides, I have to sit down and think about it myself. I am not altogether sure, and we’re working on intuition. If you make me sit down and really think through what I’m doing, you’ll spoil the process. It’s coming off the top of my head and I’m letting it flow very quickly and I don’t want to think about what it means. I hope it means nothing.”

She would object right away and say, “I don’t know what that means, to say it doesn’t mean anything.”

I’d ask, “Well, can you conceptualize that we’re trying to work on a film that wI’ll say nothing? That’s the point: to say

nothing.”

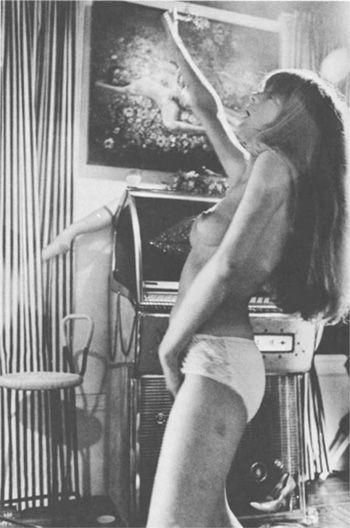

Edie performing with the Velvet Underground at Delmonico’s, for the New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry, 1966. Lou Reed, Edie, John Cale, and Gerard Malanga

She’d say, “No, I can’t.”

Once, when she saw the script of Shower—probably the best one-acter I’ve ever written, in which Edie and Roger Trudeau spend the whole thing in the shower—she started screaming, “I wI’ll not be a spokesman for Tavel’s perversities F That was the first time I’d ever heard my work described as perverse. I was to hear it in years to come from some of our best-known critics . . . but that was the first time anyone cared enough to say such a thing. I wI’ll not be in it F Edie cried, and marched out. I won’t do this F

Actually, I had the feeling that Edie didn’t really mind Shower as much as she said . . . That she’d been pushed to complain by Chuck Wein, who wanted me out of the Factory to get my job as writer-director of the films.

The end really came when Edie tore up the script of a movie called

Space,

saying she wasn’t going to memorize anything. She started to read a few of her lines: “What is all this about? How stupid!” and tore it up, right in front of everybody. That’s when I walked out. That may have been the last time I saw her.

RENÉ RICARD

The Warhol people felt Edie was giving them trouble—they were furious with her because she wasn’t cooperating. So they went to a forty-second street bar and found Ingrid von schefflin. They had noticed: “Doesn’t this girl look like an ugly Edie? let’s really teach Edie a lesson. Lets make a movie with her and tell Edie she’s the big new star.’” They cut her hair like Edie’s. They made her up like Edie. Her name became Ingrid superstar . . . Just an invention to make Edie feel horrible.