Edie (23 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

When I went to Harvard, I suddenly learned that rich kids do not have it better than others. They’re sail locked into something. I was coming from die cold of prison and these people were coming from the warmth of a six-thousand-acre ranch, but, good God, they stI’ll can’t get out!

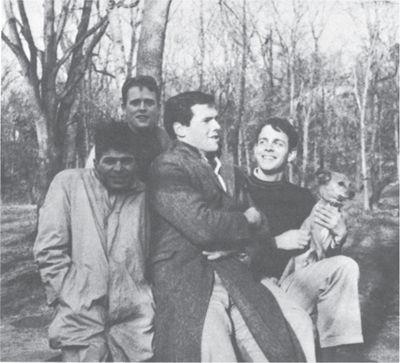

Bobby with his friends Gregory Corso

(left)

and Christopher Amanda

(right)

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

My mother’s big concern about Bobby was that his hair was too long, and she wrote him a letter saying that if he went around Harvard like that, people would think he was a homosexual.

LETTER FROM FRANCIS SEDGWICK TO NITA COLGATE, MARCH 9, 1957

. . . Bobby continues to be a fearful and increasing problem. I discovered that in the last a years he has spent all his slender capital (about $25,000—wait tI’ll he tries to earn that amount !) and he fell into a passion with me over the telephone for not handing him out $3000 instantly “for psychoanalysis” at the same time he was trying to dig $10,000 from Mrs. de Forest for the same purpose (she telephoned us in desperation) and swore he never wanted to see either parent again ever—“they” were the cause of all his troubles. Well!

ALEXANDER SEDGWICK

Around this time you never knew what sort of person you were going to meet when you saw Bobby. One day Bobby would be High Porcellian and the next day a Marxist . . . talking about organizing the workers. He could be open and charming one day, and the next day turn off, withdraw, or be incredibly rude. After he graduated in 1956, he did some graduate work in Oriental art at the Yenching Institute at Harvard. But at the same time he got involved at the Massachusetts Institute of Mental Health, where in helping the underprivileged he began to get interested in radical politics.

JOHN P. MARQUAND, JR.

He got slowly further and further to the left. I remember he came around one night—Barbara and Jason Epstein were there—and he was on an intense Maoist kick. It would be hard to be more intense than Bobby was. That evening he began talking about the incursions of the aggressive Tibetan neo-fascists against the People’s Republic of China. I remember Jason saying, “Don’t you think that’s a little far afield?”

LETTER FROM FRANCIS SEDGWICK TO NITA COLGATE, JUNE 4, i960

. . . Bobby is reported to have a scholarship from the Ladies Garment Workers Union to study Marxian economics at N.Y.U. next winter. I never expected to be tied to David Dubinsky—a man everyone thinks highly of, but different.

Life wiggles slowly on . . . .

KENNETH JAY LANE

Bobby was an old little boy. In his labor days he wore a sort of thrift-shop zoot suit. Pale gray. We met Saucie at

Parke-Bernet for lunch and she said, “Oh, you’re wearing your anti-Christ costume today.” He had on a black shirt, a 1940s tie, and his hair was slicked back, very shiny, cheap black shoes, and one tooth out. He talked “dem” and “doses.” Terribly funny. He was all profile. His face was so thin that when you looked at him from the front it was like looking at a cardboard cut-out.

THOMAS J. MCGREEVY

I didn’t see him after college until one night in Kansas City in 1961. I’d gone down with my wife to a black bar, a wonderful place called the Mardi Gras, Eighteenth and Vine. Ella Fitzgerald would come into town to sing at the Music Hall, and then she’d come over to the Mardi Gras and improvise. Everybody’d shout: “The Queen is here . . . here’s Ella!” Great place!

Anyway, we were sitting in there. I think it was a night Dizzy Gillespie was in town. Out of the smoke and haze came this gaunt figure and he said, “Hey, Tom, man, how you doing?”

I looked around and it was Bob. He looked like Charlton Heston, only very emaciated, as if someone had

sat

on Charlton Heston.

I said, “My God, Bob, how are you? What are you up to?”

He said, “Im organizing for die ILGWU. I’m engaged to this black chick and I’m, like, really swinging with it, man—and, like, what do

you

do?”

I told him, “Well, let’s see. I’m married to this young lady, Molly. I have two children and I work for my father as a stockbroker.”

This didn’t seem to bother him at all—this conservative slant to my life. He seemed genuinely pleased to see me. “Oh, Tom,” he said, “we’re going to see lots of each other. Let’s play some tennis.”

So Bob and I got out to the tennis courts at the Kansas City Country Club, which is very, very conservative ! Sedgwick’s tennis outfit consisted of a tight T-shirt and very short white shorts. He came out onto the court smoking a cigarette. He was coughing all the time, and spitting up because of all the smoke and booze in his system. He made so much noise that from the next courts these people playing polite, crisp tennis looked over to see who was playing with this guy breathing green fumes! After about fifteen minutes Bob said, “Hey, Tom, excuse me for a minute,” and he went over to the corner and

urinated

against the fence.

Oh, God, we saw a lot of him. I met his black fiancee a couple of times. Finally he wanted to leave her, but he had backed himself into a corner. He’d say, “Listen, chick, I want out; I don’t like you any more,” and she would turn on him and say, “You’re doing that because you’re

a prejudiced son-of-a-bitch, you honkie.” So he stayed around to prove that he wasn’t. After he split up with her, he got involved with a beautiful blonde Jewish girl who was married to an older husband and had four children. He used to come over and tell us what a problem it was for him: “This girl loves me, but she doesn’t want to leave her children.” That’s one of the reasons he left Kansas City. Just before he went, he came up to me and said, Tom, I’m in terrible financial shape; I’ve got to leave Kansas City so I can get out of this married lady’s clutches. WI’ll you lend me two hundred dollars?”

So I did. I didn’t know that he’d asked the same of my wife. He also borrowed two hundred dollars from

her

just before he left.

MOLLY MCGREEVY

I saw Bobby after he moved back to New York. His apartment was like poverty-city. It was railroad-car style and there was a hole in the floor about the size of a tennis ball through which you could see the apartment below. Bobby was very depressed. He seemed aimless, no work, quite broke. He had a catatonic tone in his voice. In Kansas City he’d play it cool like an intellectual, but he got excited if you argued with him over some point. But in New York he had only just a fleck of emotion. That was the last I saw of him.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

I had to put Bobby in Bellevue on August 20, 1963. a few months before Minty was admitted. He called me from a booth in the street and I could tell from his speech that he was in great trouble. He ran out in the middle of admission procedures and began trotting up the sidewalk. That beautiful boy, in his loose gray hospital pajamas. Two guards went and got him.

I called my mother and begged her to help because I just didn’t have the means. My husband was earning maybe ten thousand dollars a year at that point, and I was five months pregnant. “If you could see him, I know you would help.” I was crying and begging, “Please come.”

My father got on the phone. “Stop it. You’re upsetting your mother,” and he hung up on me.

I was distraught. I called Edie’s former doctor, Jane O’Neil at Bloomingdale, to get her to intercede with my parents and she told me very firmly to get hold of myself, that Bellevue was as good a place as any in an emergency and that my parents had a lot to bear. She said my brother could spend the night there and be tested and then be moved to a private hospital after diagnosis. Bobby stayed in Bellevue for ten days, and then he was committed to Manhattan State Hospital, that ghastly institution on Ward’s Island underneath the Triborough Bridge.

As far as I know my father never came, but eventually they did pay for him to go to the Institute for Living in Hartford. I only went up there once to see him because I was nursing my son. As I was leaving I told Bobby that I loved him and he cried. He was fat! That beautiful boy was fat from the drugs. He walked like a fat man. His hair was turning gray. He had lost that marvelous physical beauty he had when he was younger, and the feeling of power. And there was something almost . . . if s strong to say . . . eunuchlike about him . . . something soft and unmanly. They had him at work there making those appalling, clumsy ashtrays.

SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG

While Bobby was at the Institute for living, he wrote me a long letter asking for my help in getting him accepted at the Harvard Graduate School as a Special Student in Fine Arts in the fall of 1964.1 had the feeling that if we could attach him to a serious, at least paraprofessional interest, I could give Bobby the feeling that he was committed to something; it might serve not only as a concrete training but also as a very significant kind of psychological support for him. He needed a platform, an anchor. I felt so strongly about his quality as a person and an intelligence that I thought he deserved my taking the responsibility for his coming back, and I succeeded.

MARIANA WINKLE

Just before Bobby returned to Harvard for his graduate work, he went out to his younger brother Jonathan’s wedding in Santa Barbara. I had known both Bobby and Jonathan in Cambridge, and the wedding was my first visit to the ranch. Jonathan was going to marry Louise Veblen, who was the daughter of the editor of the Santa Barbara newspaper. Her family lived at the far end of the Valley and were close friends of the Sedgwicks. This was the first time Bobby had been home for years.

One evening after dinner there was almost a physical confrontation between Bobby and his father over me. It started out as verbal play, but after a while I felt like a hunk of meat between two dogs. My approval was not asked for, but that was not what was important. It was father and son hitting heads. I had been talking to Mr. Sedgwick after dinner in front of the fireplace. It was a warm night, but the fire was lit. It had been a kind of engagement dinner, quite a big thing, and everyone had been drinking. It was quite dressy. In those days everyone wore short evening dresses. Mr. Sedgwick and I were having

a general conversation about God knows what, but when Bobby entered the room it became very personal . . . about how desirable I was, and to whom I belonged. Mr. Sedgwick said something like, “I got here first. She’s mine.” Then Bobby called his father an old lecher. Mr. Sedgwick said Bobby always arrived late on the scene and caused trouble. In the middle of this it came out that Bobby had come out to try to make Jonathan’s fiancée, and if he couldn’t, he would settle for me.

The whole thing started out being sort of friendly. Then it got serious, with the two of them pushing at each other’s shoulders. At that point, I got really uncomfortable and I said, “Quit it, this isn’t funny any more.” When I got up, it broke the tension and that was the end of it. But Bobby stormed out.

I remember Jonathan’s fiancée felt uncomfortable with Mr. Sedgwick’s attention. She was a very voluptuous sort of girl, who sometimes didn’t wear a bra, which in those days was unusual. She said to me, “God, he hugs me awfully hard when I don’t wear a bra.”

SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG

When Bobby returned to Harvard that fall, he was not the graceful person he used to be. He was conspicuously heavier. The whole person had become roughened. That deliberate roughness he’d acquired had stuck. You had the feeling that he hadn’t shaved that morning, or that the clothes seemed not so much casual as shapeless. Deliberately he had exorcised a measure of his native grace and cultured background, the quality of that background. It wasn’t gone, but he had tried to put it away.

He had invented a way of speech to disguise his background. It was the damnedest noise. It sounded so absolutely unright coming out of Bobby. But then after a while all this play-acting began to pall. I think he felt it was for him a kind of hollowness.

He didn’t come and see me as much that year. He was not as dependent. He had matured significantly and didn’t need someone to talk to, talk at, be sympathetic with. Despite his appearance, he seemed so much more self-reliant.

WILLIAM ALFRED

Bobby had a lovely Mexican girl with him at Harvard—gentle, beautiful, funny. They would come over to my house for a drink two or three times a week, this very beautiful girl riding pillion on the back of his motorcycle. He was an entirely changed person, except that he did have that reckless streak. He rather fancied himself—as all people do who ride motorcycles—in a somewhat vain

way. He saw himself with his hair blowing in the wind—that sort of thing. He didn’t wear a helmet, though I kept nagging him about it. I’d lost two students because they didn’t wear their helmets.