Edie (2 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

The Sedgwick Pie, Stockbridge, Massachusetts

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

Although Judge Sedgwick lived in Boston toward the end of his life when he was Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, the family was always based in Stockbridge, where the Judge had built the Sedgwick mansion just after the Revolution. It has always been the Old House to the family, and a real haven and home. They lived rather quietly, always well educated and fairly well off, brought up to think of themselves as neither rich nor poor.

JOHN P. MARQUAND, JR.

It’s important to think of the Sedgwicks not as Bostonians but as from Western Massachusetts—what the Kennedys call “the Western

pate

of the state”—Berkshire County about fifteen miles below Pittsfield, which is the main metropolis in that area. The only Sedgwicks who could even remotely be called Bostonian were those who married into Bostonian families. Historically, this part of the state was once heavily populated with the Stockbridge Indians, who were much more interesting than anybody else, including the Sedgwicks. Jonathan Edwards, the great Calvinist divine and hellfire-and-brimstone preacher, was sent up there to establish a mission when he fell into disgrace with the Hartford establishment of the church. He was sent to Stockbridge to do penance, and it may be that the Indians were the first to hear his famous sermon about man’s soul . . . the one where he says that the grace of God is the strand of web which keeps a man suspended above the fires of hell. Robert Lowell wrote a beautiful poem about that—“Jonathan Edwards in Western Massachusetts.”

The irony is that today on the site of Jonathan Edwards’ residence is the Riggs Center, a very fancy nut house for young people. Some of the Sedgwicks passed through there. If s right across the street from the Old House.

Stockbridge and the Sedgwick tradition can be somewhat intimidating. One year I took Norman Podhoretz, the editor of

Commentary,

up to see Stockbridge and the Sedgwick Pie and the rest of the Sedgwick world . . . a sort of cultural exchange in which I was going to take him on a tour of Waspland. I told Norman that it was going to be like taking a trip to the other side of the moon. To give him a bit of a foretaste of what he might be running into, I had him read

In Praise of Gentlemen,

written by my great-uncle Henry Dwight Sedgwick, who was called Babbo in his family. It produced quite a reaction. As Norman and his wife, Midge Decter, were putting their suitcase in the

trunk of our car, he said, “Look, I’ve got to tell you before we go anywhere that I

hated

that book by your uncle. I don’t think I’m going to like any of those people or anything else if it’s like that book. There’s no excuse for such views.” I tried to calm him by saying that the old gentleman was from another era, and besides he was dead. Norman kept saying, “That doesn’t matter, there’s just absolutely nothing to be said in defense of a book like that. He’s taking the view that the only people who have made it are God’s gentlemen and that

they

don’t have to try any more—that’s a tremendous insult.”

As we drove along, Norman wouldn’t even help with the directions. I’d say, “Ask this guy which way to turn,” and he’d say,

“You

better do it, these are your people.” He began to get more and more apprehensive the closer we got to Stockbridge, as if we were going into some sort of enemy world. In fact, I heard afterwards he told somebody that he and Midge felt like—it was some Russian reference—yes, that they were like little people hiding in the snowdrifts from the Cossacks. The Cossacks were going to pour out of the Sedgwick house and just beat up on everyone.

The weekend turned out to be a collision of cultures. I remember at one point Norman asked me where all the Sedgwick money came from—a question he never would have asked if he had read Babbo’s book carefully: you’re not supposed to ask things like that. And that’s what I told him—that I didn’t really know, it’s just

there,

and that he shouldn’t ask, which made him furious at my implicit arrogance. But it’s a question which would occur to anyone, particularly a very intelligent man like Norman and a journalist to boot. Anyone would want to know where all that loot came from. No, it wasn’t at all easy for Norman.

I took them to see the Sedgwick Pie. It was winter with a heavy snow on the ground so that the Pie became rather more impressive or oppressive, depending on what you thought of it, with evergreens all around and this great drooping snow everywhere. Norman was trying to suppress a great deal of hostility and handle it nicely because we were friends. I pointed out a cousin of mine named Kate Delafield who was buried there, saying, “And that’s my cousin Kate.” Upon which Norman began to sing . . . he did a strange little dance . . . snapping his fingers to the rhythm of “I wish I could shimmy like my sister Kate!” Lillian Hellman, who had come along for the fun, wasn’t interested in the Sedgwick Pie. She wanted to get to the Ritz in Boston. She kept asking: “When are we going to get to the Ritz?”

Even family feeling is not unanimous about the Pie. I’ve heard

of a quarrel which took place on the main street of Stockbridge. A Cabot shouted across the street at her Sedgwick sister-in-law, “At least

my

family’s graveyard isn’t the

laughingstock

of the entire Eastern seaboard.” But most of the Sedgwicks take it very seriously. In 1971 my cousin Minturn Sedgwick, Edie’s uncle, wrote a letter to the town Selectmen asking the town to return some property next to the Pie which the family had donated to the community. By the year 2101, he prophesied, the Pie would be overcrowded with Sedgwicks, and if more land was not made available, the Sedgwicks would have nowhere to go. The Selectmen considered all this carefully and replied to Minturn that since the Doomsday date for the family was well over a century away, his anxiety seemed premature.

Minturn had always been very much involved in the traditions of the Pie. For a long time, I remember, he’d been looking for the family pall, a deep purple cloth that’s put over the casket. Apparently it was missing. The tradition was that the casket, with the pall over it, was taken about Stockbridge not in a hearse but in an open cart, like a gun carriage, drawn by a black horse and hung with hemlock and a few white lilacs. An elderly mailman, Thomas Carey, led the horse on foot. They’d leave the funeral services in the small Episcopalian stone church, St. Paul’s, and the family and friends would walk along behind the cortege. When the procession passed the Sedgwick house, it stopped for a moment of silence, and then everyone continued on up the main street to the graveyard and the Pie.

Three or four days after John F. Kennedy’s funeral I received a letter from Minturn which I gave to my aunt, who took one look at it and said, “Oh, no, no, no . . . it’s got to be

burned!

” Minturn’s letter reported that he had heard from a cousin, Charles Sedgwick, who for a brief period had done some interpreting in French for President Kennedy, that Kennedy knew all about the Sedgwick Pie, and Minturn wondered after having watched the sad but impressive events of the Kennedy funeral on television—the casket on the horse-drawn cart, the widow and the mourners walking along behind, and so forth—if perhaps Mrs. Kennedy hadn’t “borrowed” the idea from us. That was the way he put it: “borrowed”—with quotes around it. Such was Minturn’s curiosity that he sent a self-addressed stamped postcard on which I was to inform him whether it was indeed true that Mrs. Kennedy had “borrowed” our funeral procedures.

As I say, that would have been just like Minturn. The Pie meant a great deal to him. He stocked up on simple coffins—ornate mahogany coffins with gold handles just aren’t used by the Sedgwicks. But it’s

very difficult to buy a simple coffin: if you ask for just a plain Puritan pine box, the undertakers look at you with disgust and they say, “Oh, we have those for the potter’s field, Mac—for paupers, city cases.” Minturn persisted, apparently. He got a whole stack of simple pine boxes up in Pittsfield somewhere—certainly enough for his immediate family. A Stockbridge woman friend of mine who plays the organ at the church and is hired to perform at funerals told me that the local undertaker simply couldn’t understand this man, Minturn Sedgwick, who not only insisted on these plain boxes but got into them and “tested” them. He was a big man, a famous Harvard football player, and he got into his box to make sure it was long enough and would accommodate his shoulders.

ALEXANDER SEDGWICK

There’s a General William Bond in the Sedgwick Pie who may be somewhat surprised to find himself rising and facing Judge Sedgwick on the Day of Resurrection. He was one of the few field generals killed in the Vietnam War—he was picked off by a sniper as he was climbing out of a helicopter to take over his command—and he probably would have ended up in the Arlington cemetery if it hadn’t been for his Sedgwick wife, Theodora, who felt that since the General was married to a Sedgwick he ought to be buried up in Stockbridge. Theodora was a very staunch Sedgwick. She was once overheard saying to a companion at the bar in the Red lion Inn in Stockbridge: “I was a Sedgwick; therefore I am a Sedgwick.” So it wasn’t surprising that her husband would end up in the Pie. Actually, there were

two

funerals—the first at the military cemetery at Arlington, a service full of pageantry—a riderless horse with the stirrups up, and General Westmoreland there—and suddenly, just at the point when the coffin would normally be lowered into the ground, a hearse drove up and the coffin was transferred into it . . . almost as if the Sedgwicks were plucking the General from his sleep among the military heroes and hauling him back to the bosom of the family. The Army didn’t let go of him easily. It sent a detachment of Green Berets to Stockbridge as part of the honor escort. They caused quite a stir. The troops—almost a company of them—marched up and down the village streets and scared the life out of the hippies who were thronging the place in the 1960s, a lot of them draft-dodgers who must have assumed the Berets had been sent to get

them.

So General Bond was seen to his hero’s funeral in the Sedgwick Pie. He’s buried right behind Ellery Sedgwick, his wife’s father.

Elizabeth Freeman (Mumbet, 17429-1829) by Susan Sedgwick

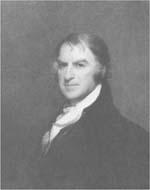

Judge Theodore Sedgwick (1746-1813) by Gilbert Stuart

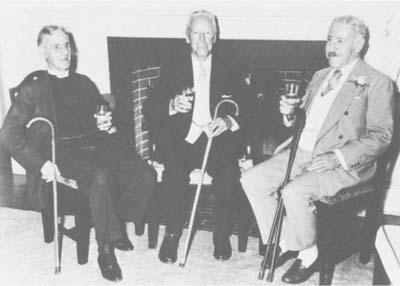

The three Sedgwick brothers

(left to right):

Theodore, Henry Dwight (Babbo), and Ellery

JOHN P. MARQUAND, JR.

My great-uncle Ellery Sedgwick is one of the best-known members of the Sedgwick clan. He became the editor of die

Atlantic Monthly

in about 1905 and maintained its influence and status during the Twenties and Thirties. I always thought him a pretentious, rather arrogant man with an enormous ego. He was born in New York in a house where Radio City Music Hall now stands, about which he says in his memoirs,

The Happy Profession

—one hopes jokingly—“What an appropriate memorial to me!” Toward the end of his life he became very reactionary—a friend of Generalissimo Franco and so forth. He was quite a snob, which was not surprising for a Sedgwick. The Sedgwicks always looked down on my father when he married into the family—they just didn’t like the idea of their darling daughter Christina throwing herself away on a penniless nobody they must have thought of as a beatnik—but when my father made it as an author, Ellery began to suck up to him. I always felt my father never should have given in to this sort of behavior, but at the end of his life he was always delighted to lunch with Ellery in Boston at the Somerset Club. When my father was young he was very insecure among them—so he must have found it comforting when they accepted him.