Eccentric Neighborhood

Read Eccentric Neighborhood Online

Authors: Rosario Ferre

A Novel

Rosario Ferré

To the ghosts who lent me their voices

Part I: Emajaguas’s Lost Paradise

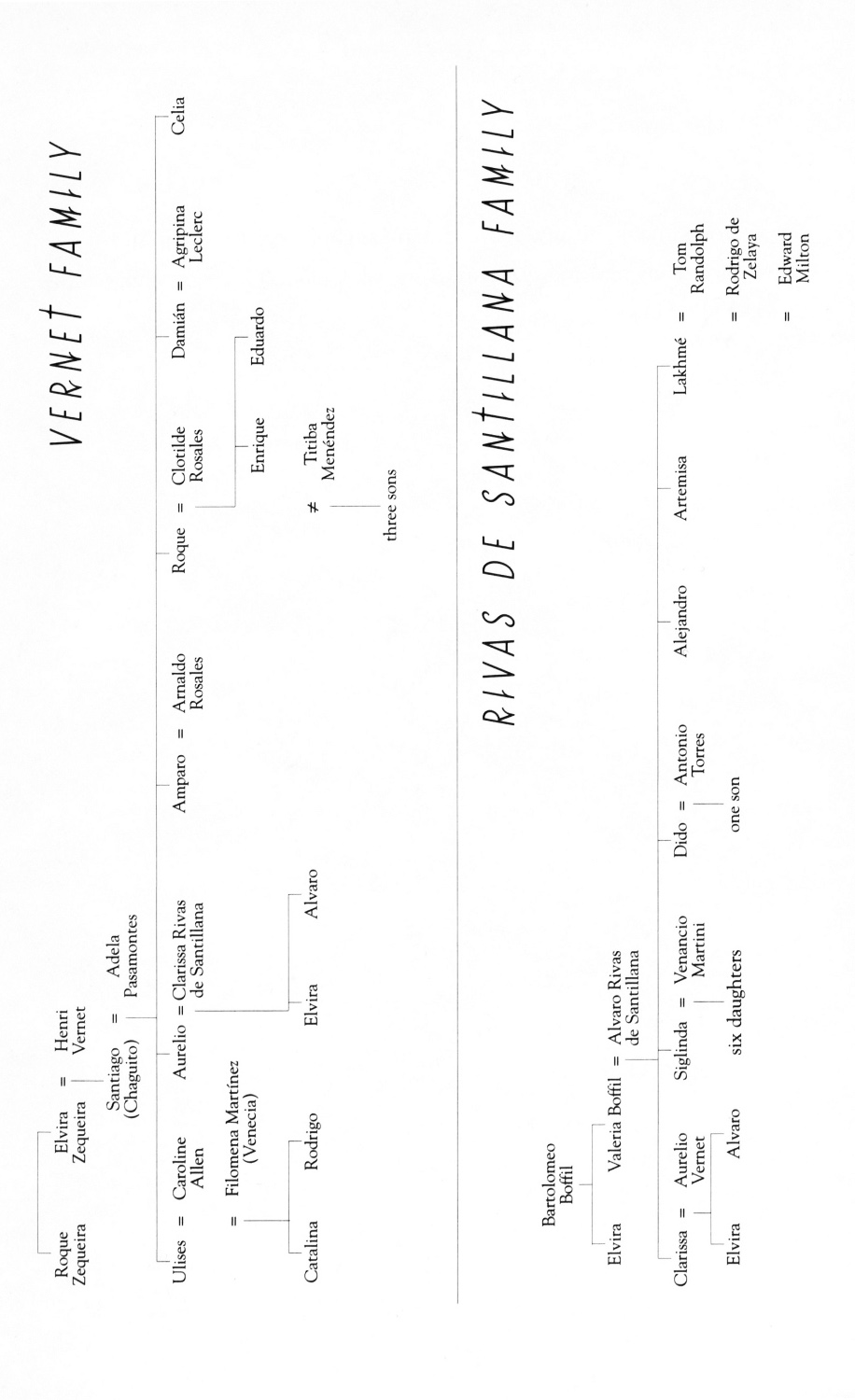

Two: Boffil and Rivas de Santillana

Four: The Piss Pot of the Island

Five: Christmas Eve at Emajaguas

Seven: Abuela Valeria’s Standoff

Part II: The Swans of Emajaguas

Eleven: The Venus of the Family

Twelve: Abuelo Alvaro’s Little Diamond

Fourteen: The Prince of Emajaguas

Fifteen: Tía Siglinda’s Elopement

Seventeen: Abuelo Alvaro Swims Away

Eighteen: Alejandro Sells the Plata

Nineteen: Alejandro Sails to Heaven

Twenty: Clarissa and Aurelio’s Wedding

Twenty-One: The House on Calle Virtud

Part IV: The Vernet Family Saga

Twenty-Two: Sailing Down the Caribbean

Twenty-Three: Chaguito Arrives at La Concordia

Twenty-Four: The Lottery Vendor’s Daughter

Twenty-Five: The House on Calle Esperanza

Twenty-Six: President Roosevelt Visits the Island

Twenty-Eight: Aurelio Grabs Ulises by the Heel

Twenty-Nine: The Obedient Giant

Thirty-One: Adela Passes the Baton

Thirty-Three: The Criollo Valkyrie

Thirty-Four: The Kingdom of Cement

Thirty-Five: The Vernets’ Star Begins to Rise

Thirty-Seven: Statehood and Sainthood

Thirty-Eight: Fernando Martín’s Mustache

Thirty-Nine: The Wedding Piano

Forty-Two: Mirror, Mirror, on the Wall

Forty-Three: Father Runs for Governor

Forty-Four: The Queen of Music

Forty-Five: Venecia’s Passage to Heaven

Forty-Seven: The Financial Wizard

Forty-Eight: Joining the Holy Roman Empire

Fifty: Roque’s Russian Roulette

Fifty-Three: Fosforito Vernet’s Last Spark

Fifty-Four: Xochil’s Converse Sneakers

Fifty-Five: The Cardinal’s Dinner Service

Fifty-Six: The Family’s Sacks of Gold

Fifty-Seven: Rebellion at the Beau Rivage

Fifty-Eight: Clarissa’s Passing

EMAJAGUAS’S LOST PARADLSE

G

EOGRAPHIES CAN BE SYMBOLIC

; physical spaces determine the archetype and become forms that emit symbols.

—

OCTAVIO PAZ

,

Postdata

Fording Río Loco

R

ÍO LOCO GOT ITS

name because it was so temperamental. When it rained in the valley and the other rivers stampeded toward the sea like runaway horses, Río Loco was dry. But when the sun was nailed to the sky like a hot coal, charring the cane fields and forcing the scorpions out of their burrows to look for water, it reared up like a muddy demon and tumbled this way and that over the dusty plain, enraged at everything that stood in its way. The river’s source was far away in the mountains, and when it rained the floods rose, even when there was fair weather in the valley.

Río Loco always reminded me of my mother, Clarissa. We would be sitting peacefully in the pantry having breakfast—Aurelio, my father, would be reading the paper, Alvaro and I would be reviewing our homework before leaving for school—when Clarissa would suddenly rise and run to her room. Aurelio would follow hurriedly behind her. As I left for school in the family’s Pontiac, I could hear Clarissa’s sobs behind closed doors, mingled with the apologetic murmur of Father’s voice.

She never explained to me why she cried, and if I insisted on asking, I risked putting myself at the mercy of one of her sharp pinches or an angry yank at a tuft of my hair. It was as if it were raining in her mind, when all around her the sun was shining.

Once a month Clarissa and my aunts journeyed to Emajaguas from different parts of the island to visit Abuela Valeria. I used to accompany Mother on these trips. Family was very important then.

I always knew when we were driving to Emajaguas because Crisótbal Bocanegra, our black chauffeur, would start whistling softly as soon as he was told of the trip. Crisótbal had a good-looking girlfriend in Guayamés, and when we traveled there he always spent the night with her, happy to get away from his wife.

Crossing Río Loco was one of the high points of our journey to Emajaguas. The old winding road from La Concordia to Guayamés had been built by the Spaniards, and although the towns were really not that far apart—twenty miles at most—the journey took two and a half hours, much longer than it should have. Father always joked about it with Mother and said the Spaniards had used the “burro method” when they built the road: they took a burro from La Concordia to Guayamés, let it loose, and followed it as it ran home down the shortest path.

Río Loco remained without a bridge through the 1940s; it was the last important river on the island to be spanned by one. The government was too impoverished to build one until the 1950s, when a human wave rose from the island and thousands of immigrants crashed into New York. They were desperately poor, and in the Bronx and in Harlem they’d still be poor, but a little less so. The bridge was good for the local economy, and soon the government began to invest in public works.

Río Loco was shallow, and most of the time we could drive across its dry gully without any problem, skirting the huge boulders that lay on the bottom like dinosaur eggs and the massive tree trunks left by intermittent floods. Come September, however, Río Loco was often flooded, and its waters pulled along everything that clung to its banks. Most of the poor peasants who worked the

central

Eureka cane fields lived in barracks; they cooked outside on coal stoves and shat in the latrines the owners had built for them. The company store was nearby, and there they could buy food on credit when they ran out of money and obtain medical supplies and services. But workers living in the barracks were closely supervised by the overseer, who would keep a tally on their debts. For this reason, some preferred the dangerous freedom of the riverbank, where they built their own shacks, to the convenience of living at the

central

. Riverbanks, like beaches, are all public property on the island.

The earth was black and fertile along the banks, and the peasants grew splendid plantains, manioc roots, and cane stalks there. But when the river flooded, it reclaimed with a vengeance the terrain it had temporarily ceded to the squatters. You could see doors, corrugated tin roofs, rocking chairs, tables, cooking pots, mattresses, all floating slowly toward the sea, as well as dogs, pigs, goats, and even cows, already swollen, pulled along, legs up, by the brown, toffee-like mass of water.

I loved crossing Río Loco when it was flooded, and as the family car set out for Emajaguas I always prayed for a

crecida

, never thinking about the havoc the river created for the peasants. It broke the monotony of the trip, the silence that inevitably sat like a block of ice between Mother and me. As we neared the river, my heart would begin to pound faster and faster. We never knew whether the current would be high or not, and if the river couldn’t be crossed, we would inevitably have to turn back toward La Concordia, with Mother in tears.

As soon as we neared Río Loco’s banks, Mother would instruct Crisótbal to drive the blue-and-white Pontiac to the river’s edge, and I would stick my head out the window to see what was going on. If the current was high, Mother would order him to pull up close to the water and we would wait in silence under a mango tree to see if it would recede. Mother could never wait very long, however. Without a quiver of fear in her voice, she would command Crisótbal to drive the Pontiac into the murky current. The car would soon be bobbing and half floating over the riverbed, maneuvering its way across the now-invisible boulders. By the middle of the river, Crisótbal would hardly be touching the accelerator; with the dangerous current flowing by on each side, we would be stranded, unable to get out.

This is precisely what happened one day. Crisótbal was following in the wake of some hardy soul who had plunged his car into the murky water ahead of us, when all of a sudden the Pontiac had an attack of delirium tremens and died midstream. Clarissa ordered us to roll up our windows, and for twenty minutes the three of us sat there in silence watching the brown water rise inch by inch until it was licking the windows, carrying with it the debris from upstream. The car was full of good things to eat that our cook at La Concordia had prepared—a leg of lamb, a roast turkey, a cauldron of

arroz con gandules

—and soon the delicious odors were all but stifling. A basket of oranges, pineapples, and breadfruit picked that morning from the garden lay on the seat between Mother and me. It was like sitting inside a watertight paradise dressed in our Sunday best—Clarissa in a printed silk georgette gown and high-heeled Saks Fifth Avenue shoes and me in my white organdy dress with a satin bow on my head—watching all hell break loose around us.

Clarissa looked at her diamond Cartier wristwatch on its black grosgrain band and saw that it was already half past eleven. If we didn’t hurry, we would be late for lunch at Emajaguas and wouldn’t be able to sit down at the table with Abuela Valeria and my aunts. Mother ordered Crisótbal to start the engine. He turned the ignition key; the car gave a couple of lurches and died on us again. Clarissa then commanded him to honk the horn. Soon four barefoot peasants dressed in faded khakis and scraggly straw hats, who had been standing on the shore with their oxen watching our predicament, waded silently into the river.

With rushing water up to their waists, they approached the car, yoked animals in tow. Clarissa opened her handbag, took out a dollar, and waved it at them from inside the window. The peasants tied the beasts to the Pontiac’s front bumper with a thick hemp rope, and slowly the car began to move forward. The smell of mud grew stronger, and I stared in horror as a thin line of water began to seep in through the bottom of the door. Clarissa signaled emphatically to the men to poke the oxen more sharply with their long poles. Once on shore, she slipped the dollar bill to the peasants through a crack at the top of the window and ordered Crisótbal to start the car. The Pontiac jumped forward, its shiny blue-and-white surface dripping with mud, and took off at full speed, an anxious Pegasus flying down the road toward Emajaguas.