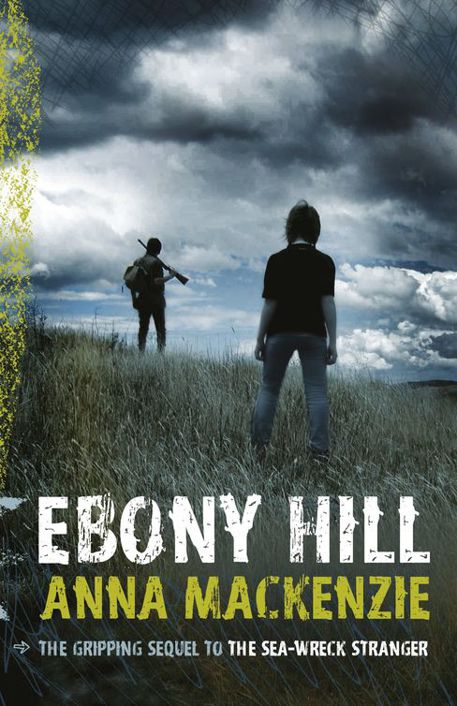

Ebony Hill

Authors: Anna Mackenzie

ANNA MACKENZIE

With thanks to Barbara Larson, Nicky Page and the team at Random House for finishing touches, and to Jo Morris, Emme Neale, Kirsty van Rijk and Embla Thorolfsdottir for early feedback. Thanks throughout to Hamish, Madeleine and Callum, and to Jane Hurley, without whom I might never have set foot on the road.

F

or Saskia,

Rory, Bec and Jess whose new horizons

will – hopefully – prove a little less daunting

.

From above the gardens that stride in wide stairs up the hillside, I look out over the wreckage of a world I’ll never know. Vidya, the city of Devdan’s promises, is all and more and none of what I expected.

For all that Dev told me before we left Dunnett Island, I had no scale to fit his stories around. The bared and broken skeletons of buildings sprawl across the heart of the old city, scarred concrete gradually giving way to a creeping carpet of green. Flags mark off the sites that are unstable or toxic, while the dark stain of fire is all that remains of the housing that once cloaked the hills.

But the city is more than ruins. Not far from where I stand, the buildings of the old university spill down the hillside like a tumbled stack of blocks, covered walkways spidering between them like veins. The university is Vidya’s heart and purpose. ‘Knowledge is both past and future: salvage, enhance, extend’ it says above the archive doors. The motto makes a mockery of the game my brother Ty and I once played, speculating on the sea-wreck

that washed up in Skellap Bay.

As I step into the trees that hide the path to the headland, I let out a small sigh. Wind whispering through the storm-battered branches almost lets me forget the ruined city at my back – almost, but not quite. Its tainted air still curls into my nose and its towers loom empty-eyed, even unseen.

Whenever the smog-count allows I escape to the headland. Esha doesn’t approve such a use of my time. “You should learn to like your own company less,” she says, but it’s not for solitude that I come. Maybe she knows that too.

After nearly two years in the city, I still don’t feel easy with the constant press of people, nor with the noise and hurry of their lives, but what troubles me more, what I come here to acknowledge, is the sense of loss that Vidya’s brought me, alongside all its gains.

A gust of wind curls across the ridge and I close my eyes, the better to taste its salt breath and the memory it brings of Dunnett Island, of my brother Ty and cousin Sophie, of running with the tide along the sand of Skellap Bay.

Like a shadow the memory shifts and Colm Brewster stands before me. Colm, who pronounced that nothing remained of the world beyond our island, and that only evil came of the sea-wreck that washed up on Dunnett’s shores.

At a sound my eyes fly open, shoulders hunching as I flinch.

“Are you all right, Ness? I didn’t mean to startle you.”

Anjan’s familiar voice pulls me back to myself, winnowing my memories into line. “I was remembering something.” I try to smile.

Anjan is younger than me, the same age as Sophie left behind on Dunnett Island, and we share Marta as our mentor. Like me, Anjan’s an orphan.

“Have you been out to the headland?” I ask.

She shakes her head. “I like the trees. Marta says I should apply for the land-sci programme.”

I nod. Marta has advised me likewise to consider a placement in research. I’ve not told her that if I did my preference would be sea-sci: I know without hearing that my reasons won’t stand up to her scrutiny.

“You should,” I tell Anjan. She’s fine-boned as a sparrow and as quick. In class her brain takes a grip on new ideas more readily than mine.

“Grand-da thinks it’s the right choice,” she says, then cocks her head to one side. “He says you’d be best in med-sci. He told me before he left for the farms.”

I frown. I met Anjan’s grandfather, Jago, soon after I arrived in Vidya – he’s head archivist and records the stories of all newcomers to the community – but he’s not chosen to share with me his views on my future.

“You must miss him,” I say. I had been sorry to see Jago exiled by the city’s smoggy air, but after a winter where each of his breaths was reduced to a battle, Esha had been firm about his choices.

At his farewell, Jago had joked about being banished to the farms. “I’ve been in archives long enough,” he’d said. “A career in ag-sci might suit me.”

But I’d known, looking at his sunken chest and the lines that age and illness had written on his face, that he’d been put out to pasture, like a draught horse too old to pull the plough.

“I do,” Anjan says. “I miss him more than you can imagine.”

Though I doubt that’s true, I don’t say so.

“Esha says he might be able to come back to visit in the summer.”

Esha is constantly seeking solutions for everyone’s problems, fraying herself thin as an old dishcloth in the process of finding them. It’s no easy burden, being responsible for the community’s health.

“Or else she says I could sign on for the seasonal crew that helps with the harvest. I’ve never been to the farms,” Anjan adds with a frown. “I’m not sure I’d want to be so far from home. Oh!”

I shrug. From the day I fled Dunnett, the island was lost to me. Thanks to Dev, I’ve since counted Vidya my home.

“I didn’t mean …” Anjan begins and trails off.

“It’s all right,” I tell her, but she bobs her head and darts away along the path.

As I walk on toward the headland, I nudge cautious as a mouse through my memories. By the time Dev found his way across the ocean to Vidya, I’d long since lost track of the days we’d been at sea. I’d lost track of about everything. It was Esha who coaxed our shrivelled and sun-battered bodies back to health and Esha, as well, who helped me find a place for the grief that squeezed my heart.

Dev recovered far quicker than I did, shrugging himself back into the life he’d led before he met me the way you might slip on an old coat – one fitted too close to offer shelter for two. Esha tried to help me come to terms with that too.

Maybe more than I did, she understood how much leaving Dunnett had cost me. It was her idea that I stay on at the med centre even after I’d recovered, and not because Dev told her that I had a talent for healing, that he wouldn’t have survived if it weren’t so. When she spoke to the governors on my behalf, she said the last thing I needed was more changes. She said I shouldn’t be troubled by anything more than finding a way to belong.

Esha, as much as Dev, is my family here in Vidya.

Where the path snakes out of its thin wrapping of trees, I stop to pull my hair into a plait that locks it away from the wind’s wily fingers and cast my eyes back across the city.

The smog is thin today, so that I can see past the looted malls – consume-alls, Esha calls them – to the tower that Dev told me once housed all the wealth of the old city. I didn’t understand how you could keep wealth in a building. Wealth is rich soil and a harvest gathered in before the winter. Wealth is productive land. Dev laughed when I said so, and told me I belonged at Ebony Hill.

Turning my back on the ugliness of the ruined city, I scramble up the bank where the path has long since been swept away. At the top of the slope, a platform of cracked tarmac, its surface ruptured by a hundred weed-seamed

scars of time and heat and cold, spreads its grey stain across the soil. Beyond, the barrier that once held the hilltop in check leans drunkenly out towards the ocean.

Closing my eyes I taste the brine-laced air on my tongue. Just for a moment, I let my thoughts slide across the sea to Dunnett.

Leaves will have begun to tip the trees in green and it’ll soon be time to plant out the early vegetables. It will be Sophie who has taken over the tasks that once were mine, tending the goats and gardens and milking old Sal. Ty will be nearly full-grown. Marn will have him working dawn to dusk in the fields at planting time and harvest. Against my closed lids, memory paints the outline of Cullin Hill.

No matter how much you might want to leave a place, if it’s where you were raised it holds a piece of you it doesn’t easily give up.

A gull shrieks. Chest filled to bursting with the salty tang of memory, I open my eyes. The sky is taut-bellied above white-ruffled waves. Across the channel – my heart skips and kicks, all thoughts of Dunnett fleeing like dawn fog before sunlight. Near the rocks that guard the harbour’s narrow mouth, a sail billows outward – a sail I recognise, that I can only now admit I was hoping to see, that sends me skimming like a gull down the hill, through the trees, back into the heart of the old city.

Esha calls a greeting from the steps of the med centre as I pass. I hesitate. The ship will take an hour or more to angle its way into the inner harbour.

“

Explorer

is back.” The words burst out of me. “They’re just now coming through the heads.”

Esha’s mouth lifts in its customary gentle smile. “Ah.” She pushes a hand through the short black spikes of her hair. She looks tired, shadows emphasising the lines that spider out from her eyes. “They’ve been away longer than Lara expected. I hope that means the news is good.”

I nod. Dev told me the trip would last six weeks but it’s been closer to nine. “Dev was sure the northern fishing grounds would be safe again by now.”

Esha gestures me into her office. “If we could fish again it would make a difference to our diet that I, for one, would welcome.” She pauses. “You’ve been up to the headland?”

Uncomfortable under her scrutiny, I let my eyes roam the familiar room, its walls tight-packed with shelves of medical texts. On Dunnett books are burned, alongside everything else the Council blames for the damage the world’s suffered. I’ve seen more of that damage than the islanders ever have, and I know it’s not books that are to blame – or ‘tecknowledgie’ as Colm would have it. At least not all of it. Unlike Colm and his Council, I’ve also seen the good that study and research brings. I have Vidya to thank for that.

“You need to spend less time alone, Ness,” Esha says, in a familiar refrain.

“I went with Anjan,” I claim. “Only she didn’t go as far.” My pale skin betrays me: I feel myself colour.

She lifts a sceptical eyebrow. “Perhaps Anjan doesn’t share your interest in the comings and goings of Lara’s sea-sci research team.”

I tilt my head to acknowledge her views – and my right to ignore them.

She tries a new tack. “Devdan will be pleased that Marta has given consent for you to start your placements. Have you made a decision yet, Ness?”

“Not yet.” I change the subject. “Anjan was talking about Jago. Will his lungs heal at the farm?”

The furrows between Esha’s brows pull tight, aging her beyond her not quite forty years. “He’ll breathe easier in the cleaner air, but the damage – Ness, you know what the air here is like. A lot of our older people develop problems.”

I purse my lips.

“It’s less an issue now that our monitoring has improved.”

Knowing when the smog is most toxic so we can hide behind masks or cower indoors is not a solution that sits easily with me. My tongue nudges hard against my teeth, as if I might bar Vidya’s tainted air from my lungs.

“I was wondering, Ness, whether you could spare me a few hours tomorrow. I’ve been so busy since the accident in the old docklands that I’ve not had a chance to finish logging the new vaccine trials.”

I wince at the memory. Six members of the decontamination crew had been injured, four badly, when a wall collapsed in a warehouse they were clearing. I’d been with Esha when they carried them in.

“They’ll recover,” she tells me.

I bob my head. Decon is dangerous work, but it’s rare to lose lives.

“I’ll have to schedule health scans for

Explorer’

s crew as well,” she adds. “You might prefer to help with that.”

“I’ll do the trials,” I say quickly. I’ve always shied from helping with clinics. My ignorance makes me feel too exposed.

The vertical grooves between Esha’s brows deepen and she takes the taut little breath that warns me she’s planning to say more. I glance toward the window.

Explorer

will be in the inner harbour by now. “They’ll be here soon,” I say, to forestall her.

I scarcely notice her slow sigh, my thoughts already darting ahead to the jetty.

You might think that by now I’d be accustomed to Dev being away from the city more time than he’s in it, but it still leaves an ache in my chest when he’s gone. An ache that I know the sight of him will heal.

Esha flaps a hand. “Off you go then.” As I reach the door she adds: “Take care, Ness.”

Afternoon shadows are leaning over the city. I jump down the med centre steps and dodge a maintenance crew trudging towards the food hall. Shared meals are a big part of Vidya’s daily life.

A group has already gathered by the time I reach the city’s floating jetty. My breath rasps in my throat as I slow, the amused smiles that greet me bringing fresh colour to my cheeks. I stand a little apart.

Explorer

is tracking up the harbour, prow lifting in the swell, gulls dancing across her wake. As she nears, the slight figure at the wheel raises an arm.

“Yo, Captain,” one of the men on the jetty calls.

Lara returns his greeting. As

Explorer

angles in toward the wharf I scan the deck for Dev. Ropes are tossed, caught, stretched taut as the muscles banding my chest. I take a gulp of air, brine overpowering the old city stench.

A burst of shouting and the gangplank hits the jetty and is swiftly secured. Kush is first down, escorting Tian whose arm is in a sling: fresh business for Esha. Then come Malik, Lara, Jae, each carrying cold-crates that they pass to the waiting crowd. Research? Samples? I don’t care. Someone laughs and the smell of fish reaches me – and the gulls as well. They shriek and skitter overhead.

At last I see him, climbing from the hold. Two years ago on Dunnett I saved Dev’s life; in return he saved mine, which you could say makes us even. It’s never so simple. I push a strand of hair from my face.

At the top of the gangway Dev looks up at last and sees me. He raises a hand. My heart skips as I send an answering wave, but he’s already turned to speak with someone behind him. The stranger is Dev’s height, half boy, half man. Straight brown hair falls untidily across his face as he dips his head. With a hand on his shoulder, Dev steers the newcomer – reluctance showing in every tense line of him – down the gangway. At its foot the waiting group swallows them both.

My feet are fixed to the spot. Waves cuff the jetty, my stomach lurching as I stare at the planking’s deceptive rise and fall.