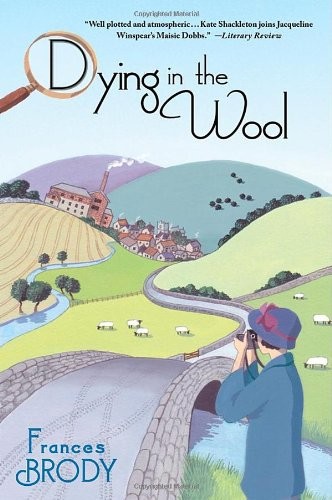

Dying in the Wool

Authors: Frances Brody

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Traditional, #Traditional British, #Women Sleuths, #Historical, #Cozy

Frances Brody

is a pseudonym for Frances McNeil, author of four novels and winner of the Elizabeth Elgin Award for best new saga of the millennium for

Somewhere Behind the Morning

. Frances has written many stories and plays for BBC radio, and scripts for television. Her stage plays have been toured by several theatre companies and produced at Manchester Library Theatre, the Gate and Theatr Clwyd, with

Jehad

nominated for a

Time Out

Award.

Frances lived in the USA for a time before studying at Ruskin College, Oxford, reading English Literature and History at York University, teaching English and History at Bradford College and tutoring writing courses for the Arvon Foundation. She lives in Leeds where she was born and grew up.

Dying in the Wool

is Frances's first crime novel. Frances says, “Murder, mystery and family secrets have always fascinated me and featured strongly in my writing. Kate Shackleton sprang to life from our family album, circa 1920. She came carrying her camera, looking at me, looking at her.”

To find out more about Frances, visit her website at

www.frances-brody.com

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 978-1-405-51170-4

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2009 by Frances McNeil

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

In memory of Peter

Inspector Singh Investigates: A Most Peculiar Malaysian Murder

Bradford once had its mill millionaires who owned more Rolls Royces per silk top hat than London. The mills are silent now. Those that did not mysteriously catch fire years ago have been converted to other uses.

Bridgestead will not be found on any maps nor Braithwaites Mill in the trade directories.

My name’s Kate Shackleton. I’m thirty-one years old, and hanging onto freedom by the skin of my teeth. Because I’m a widow my mother wants me back by her side. But I’ve tasted independence. I’m not about to drown in polite society all over again.

Seven o’clock on a fine April morning, cosy under my blankets and red silk eiderdown. Through the open curtains I looked at the blue sky with its single small white cloud. In Batswing Wood, a blackbird sang. A crow alighted on my window ledge, head tilted, beady eye peering as I swung myself out of bed, planted my feet on the lambs-wool rug, stretching and curling my toes. Crow visitor turned tail, plopping a parting souvenir on the window sill.

Time to start the day. From downstairs came the sound of the letter box, first a rattle then a series of gentle thuds as post hit the mat.

As I brushed my teeth, a horse clip-clopped along the road towards Headingley Lane.

The back door opened. Mrs Sugden would be at her self-appointed task. She would clank round with bucket and shovel, stepping along the little path to the road, and scoop up horse muck. Manure. Good for the roses, she says. Waste not, want not. But how much fertiliser does one garden need?

A small mountain of horse dung grows between the coal shed and the fence that separates the back garden from the

wood. Resident armies of flies and bluebottles delight in its stench.

Knowing that some people, particularly my mother, hold my way of life and pastimes odd, I don’t like to interfere with Mrs Sugden’s manure habit. For a reason I dread to fathom, my housekeeper has appointed herself horse muck monitor for the neighbourhood.

I live a short cycle ride from the centre of Leeds, not far from the university, and from the General Infirmary where Gerald once worked as a surgeon. Ours is the lodge house, sold off by the owners of the mansion up the road when the new occupants cut down on staff. A neat extension provides Mrs Sugden with her own quarters, a situation which suits us both.

Because of the university and the infirmary, we have our fair share of soaring intellects in this part of the world, though I don’t count myself among them. My nose for solving mysteries comes from having a police officer father, a poke-your-beak-in persistence and an eye for detail.

Dressing gown round my shoulders, I sat on the bed and pulled on my stockings. Knees are a very strange part of the anatomy. Mine are too bony for my liking. As I contemplated my knees, I thought of the mystery I have not yet solved. My husband Gerald went missing, presumed dead, four years ago.

Like a sleepwalker, I allowed his and my family to persuade me into claiming insurance, transferring the house into my name, and drawing down his legacy. Financially, I am secure. I do the things we humans have devised to find some meaning in life. The sleepwalking is at an end, yet my world stays out of joint.

Try as I might, I have not yet been able to find an eyewitness to Gerald’s last moments, or to discover the circumstances of his death.

The only news of him, if you could call it that, can be summed up in a few words. Captain Gerald Shackleton of

the Royal Medical Corps was last seen in the second week of April, 1918 on a road near Villiers-Bretonneux, following heavy bombardment. There had been gas in the valley and many casualties. Gerald had taken up position in a quarry, his stretchers and supplies stored in a large cave. He had written to me that there was so little he could do in a first aid post – just make the men feel better for having him there. A shell hit the quarry. His stretcher-bearers were killed and supplies destroyed. The few men that were left set off to walk to Amiens. I tracked down a lieutenant who spoke to Gerald on the road. The lieutenant said that there was barrage after barrage. Somebody must have seen Gerald again, just once. Somebody must know what happened.

Four years on, one side of my brain knows he is dead. The other side goes on throwing up questions.

It was after Gerald went missing that I began to undertake investigations for other women. I have uncovered some clinching detail about a husband or son, some eyewitness account from a friend or comrade. As late as 1920, I tracked down a soldier who had lost his memory, and reunited him with his family. One officer I traced last December remembered only too well who he was and from where he hailed. He had simply decided to turn his back on family and friends and begin a new life in Crays Foot, cycling to work each day at the Kent District Bank.

I wake in the night sometimes, startled, with the sudden thought that Gerald may still be somewhere on this earth – not dead but damaged and abandoned.

Searching for people and information, sifting through the ashes of war’s aftermath, drew me deeper into sleuthing. Where I failed for myself, I succeeded for others. It’s something useful I can do.

The enticing aroma of fried bacon drifted up the stairs, snuffing out my reverie and propelling me towards the wardrobe.

Opening the wardrobe door makes me groan. I can pounce on something wonderful, like the pleated silk Delphos robe, my elegant black dress, stylish Coco Chanel suit and the belted dress with matching cape that you can’t get a coat over. These outfits are squashed by pre-war skirts, shortened to calf-length, divided cycling skirt, and the shabby coat I wore when setting off with the other Voluntary Aid Detachment women and girls from Leeds railway station back in the mists of time. Fortunately I have several afternoon dresses. Mrs Sugden and I peruse the ‘Dress of the Day’ in the

Leeds Herald.

She can make a fair copy of almost anything and I am an excellent assistant.

I pulled on my favourite skirt and took a pale-green blouse from the drawer, vowing to shop this very week and become highly stylish. I topped off my outfit with a short military-style belted jacket. To go downstairs in anything less substantial would draw Mrs Sugden’s warning to ‘Never cast a clout till May goes out’.

Glancing in the mirror, I brushed at my hair. Before the war, I wore it long. In some ways long tresses made life easier, except on bath night, but I shan’t grow it again. If hair could speak, I suspect it would express a preference for length. It takes against me and has to be forced with water and brush into lying down.

After breakfast at the kitchen table, I poured a second cup of tea and reached for the post.

Mrs Sugden busied herself at the kitchen sink. She has a look of Edith Sitwell, with the high forehead and long nose people associate with intelligence and haughtiness. She turned her head and primed me in her usual fashion. ‘You’ve only two proper letters. One from your mam.’

It would not amuse my mother to be called ‘your mam’.

I slit open my mother’s letter first because it would be bound to contain instructions of some kind.

Mother reminded me that she had booked our railway tickets to London for 11 April, a week on Tuesday. I like Aunt Berta and wouldn’t want to miss her birthday shindig. She and Uncle Albert live in Chelsea, in a house that expands as you enter.

‘Don’t bring that same black dress,’ Mother wrote. ‘You have worn it for the last three years. And before you say you will wear the Delphos robe, don’t forget who passed it on to you and that it is practically an antique. We will shop in London but before that I will catch the train to Leeds this coming Monday. You and I will visit Marshalls for an evening gown. It is time for a burst of colour.’

I’m sure there must have been a time when I liked shopping for clothes. Hmm, Monday. Today was Saturday. It might not be so bad. I could do that. Would have to do it. Yet … I might as well admit now that my aversion to buying a new evening gown is compounded by the totally illogical feeling that if Gerald does by some miracle come back, and we go out to celebrate, I ought to be wearing something he will recognise. I know that makes me irrational and a suitable case for treatment but there it is.

The brown envelope held my application form for the 1922 All British Photographic Competition, closing date 30 June. I have been a keen photographer since Aunt Berta and Uncle Albert bought me a Brownie Outfit for my twentieth birthday. I still remember the delight in cutting the string, folding back the brown paper, opening the cardboard box and discovering item after item of magical equipment. There was the sturdy box camera, ‘capable of taking six 3

1

/

4

x 2

1

/

4

inch pictures without re-loading’, the Daylight Developing Box, papers, chemicals, glass measuring jug and the encouraging statement that here was ‘everything necessary for a complete beginner to produce pictures of a high degree of excellence’. I subscribe to the

Amateur Photographer

magazine and occasionally

attend the slide shows and discussions of the local club here in Headingley but have never yet entered a competition.