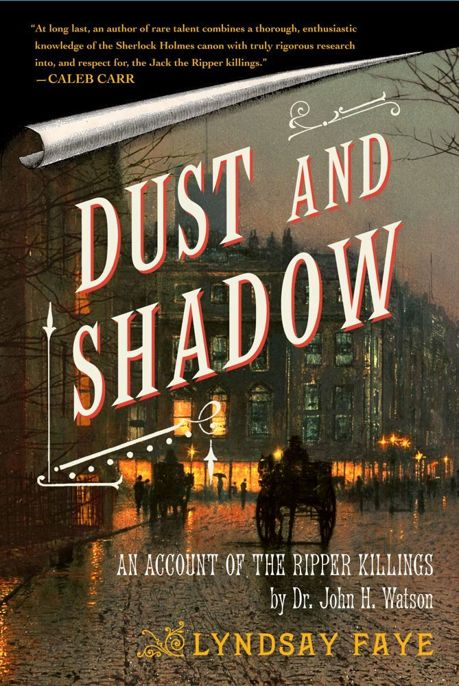

Dust and Shadow

Authors: Lyndsay Faye

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Mystery & Detective, #Traditional British, #Historical, #Thrillers

Simon & Schuster

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2009 by Lyndsay Faye

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-8362-2

ISBN-10: 1-4165-8362-9

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

For Jim LeMonds

and his Five Easy Pieces

AND

SHADOW

At first it seemed the Ripper affair had scarred my friend Sherlock Holmes as badly as it had the city of London itself. I would encounter him at the end of his nightlong vigils, lying upon the sofa with his violin at his feet and his hypodermic syringe fallen from long, listless fingers, neither anodyne having banished the specter of the man we had pursued for over two months. I fought as best I could for his health, but as a fellow sufferer I could do but little to dispel his horror at what had occurred, his petrifying fear that somehow, in some inhuman feat of genius, he could have done more than he did.

At length, though never for publication, I determined that in the interests of my own peace of mind I should write the matter down. I think only in my struggle to record the Reichenbach Falls business have I borne so heavy a weight as I laid pen against paper. They were evil days for me, and Holmes more than once, up and about as the cases flooded in with more force than he could practically avoid, leaned against my desk and remarked, “Come see about the Tarlington matter with me. You needn’t write this, my dear fellow. The world has already forgotten him, you know. One day we shall too.”

However, as was very seldom the case, Sherlock Holmes was mistaken. The world did not forget him. It has not forgotten him to this very day, and it is a brave lad indeed who does not experience a chilling of the blood when an elder sibling invokes the frightful phantom of Jack the Ripper.

I finished the chronicle, as much as possible in that measured biographical tone which had become my habit. I did so many years ago,

when Holmes’s part in the matter was still questioned. But our role in the Ripper murders soon ceased to be a topic of any interest save to a select few. Only the cases visibly solved by my friend drew the accolades of a grateful public, for a story without an end is no story at all, and for London’s sake, as well as for our own, the solution to the Ripper affair had to remain absolutely secret.

Though I may act against my own best interests, I cannot now bring myself to burn any records of the cases Holmes and I shared. I intend to leave my papers in my solicitor’s capable hands, with this particular missive resting upon the very top of my dispatch box. No matter how vehemently I may insist upon it, however, I cannot be certain that my desire to leave this account unpublished will be obeyed. This tale throws into stark relief the most distant margins of man’s malevolent capacities, and I will not stand accused of embellishment or of sensationalism. Indeed, by the time anyone lays eyes on these pages, I pray that Jack the Ripper will have faded into a mere memory of a less equitable, more violent time.

My sole intent in setting the story down at all was to applaud those indefatigable talents and high-minded purposes which I hope will ever single out my friend of more than fifty years. And yet, I am gratified to note, even as I write—beset with tidings of new war and of new grief—posterity in her kindness has already singled out a place in history for the great Mr. Sherlock Holmes.

Dr. John H. Watson, July 1939

FEBRUARY

1887

“My dear Doctor, I fear that I shall require your services this evening.”

I looked up quizzically from an article on the local elections in the

Colwall Gazette.

“With pleasure, Holmes.”

“Dress warmly—the barometer is safe enough, but the wind is chill. And if you don’t mind dropping your revolver in your pocket, I should be obliged. One can never be too careful, after all, and your revolver is a particularly businesslike argument.”

“Did I not hear you say at dinner that we would return to London by the morning train?”

Sherlock Holmes smiled enigmatically through the gauzy veil of pipe smoke which had gradually enveloped his armchair. “You refer to my remarking that you and I would be far more productive in the city than here in Herefordshire. So we shall be. There are three cases of variable interest awaiting us in London.”

“But the missing diamond?”

“I have solved it.”

“My dear Holmes!” I exclaimed. “I congratulate you. But where is it, then? Have you advised Lord Ramsden of its whereabouts? And have you sent word to Inspector Gregson at the inn?”

“I said I had solved it, not resolved it, my dear fellow.” Holmes laughed, rising from the damask chair in our elegant guest sitting

room to knock his pipe against the grate. “That work lies ahead of us. As for the case, it was never a very mysterious business, for all that our friend from the Yard appears to remain bewildered.”

“I find it just as inexplicable,” I admitted. “The ring stolen from a private vault, the absurd missing patch of lawn from the southern part of the grounds, the Baron’s own tragic past…”

“You have a talent of a sort, my dear Watson, though you make shockingly little use of it. You’ve just identified the most telling points in the whole affair.”

“Nevertheless, I confess myself all in the dark. Do you intend this evening to confront the criminal?”

“As it happens, no actual lawbreaking has yet been committed. However, you and I shall tonight don as much wool as we can lay our fingers on in order to witness a crime in action.”

“In action! Holmes, what crime can you mean?”

“Grave robbing, if I have not lost all my senses. Meet me upon the grounds at close upon one o’clock, if convenient—the staff will be largely abed by that time. I would not be seen exiting the house, if I were you. Needless delay could prove very unfortunate indeed.”

And with that, he disappeared into his bedroom.

At ten to one I quit the manor warmly bundled, for the night was bitter indeed, and the stars were mirrored by frozen moisture upon the grass. I spotted my friend with ease as he wandered down a stately path groomed with an almost Continental exactitude, apparently engrossed by the prospect of Nature’s constellations strewn across the sky with perfect clarity. I cleared my throat, and Holmes, with a nod, advanced in my direction.

“My dear Watson!” he said quietly. “So you too would prefer to risk a chill than to miss the Malvern Hills by night? Or so the housekeeper must assume?”

“I do not believe Mrs. Jeavons is awake to assume anything of the kind.”

“Marvelous. Let us see, then, what a brisk walk can do to combat this frigid weather.”

We followed a path which at first pointed toward the gardens but soon banked to trace the curvature of the nearby bluffs. It was not long before Holmes led us through a hinged gate of moss-covered wood, and we left the grounds of Blackheath House behind us. Feeling at a severe disadvantage regarding our intentions, I could not help but inquire, “You have somehow connected grave robbery with a recently stolen heirloom?”

“Why recently? Remember, we have very little evidence as to when it disappeared.”

I considered this, my breath forming ghostly miasmas before my eyes. “Granted. But if there is any question of grave robbery, should we not prevent rather than discover it?”

“I hardly think so.”

Though I was entirely inured to Holmes’s adoration of secrecy at the closing moments of a case, on occasion his dictatorial glibness grated upon my nerves. “No doubt you will soon make clear what a bizarre act of groundskeeping vandalism has to do with the defilement of a sacred resting place.”

Holmes glanced at me. “How long do you suppose it would take you to dig a grave?”

“Alone? I could not say. Given few other constraints upon my time, a day perhaps.”

“And if you required utter secrecy?”

“Several more, I should think,” I replied slowly.

“I imagine it would take you nearly as long to undig a grave, were the need to arise. And if it were imperative that no one discover your project, I presume your native cunning would suggest a way of hiding it from public view.”

“Holmes,” I gasped, the answer suddenly clear to me, “do you mean to tell me that the missing patch of sod—”

“Hsst!” he whispered. “There. You see?” We had crested the top of a wooded ridge perhaps half a mile from the estate and now peered

down into the rough depression forming one of the boundaries of the nearby town. Holmes pointed a slender finger. “Observe the church.”

In the vibrant moonlight, I could just make out through the trees of the cemetery the stooped figure of a man laying the final clods of dirt upon a grave graced with a diminutive white headstone. He wiped his brow with the back of his hand and started directly for us.

“It is Lord Ramsden himself,” I murmured.

“Back below the crest of the ridge,” said Holmes, and we retreated into the copse.

“He is nearly finished,” my companion observed. “I confess, Watson, that my sympathies in this matter lie squarely upon the side of the criminal, but you shall remain behind this outcropping and judge for yourself. I intend to confront the Baron alone, and if he proves reasonable, so much the better. If he does not—but quick, now! Duck down, and be as silent as you can.”

Settling onto a stone, I lightly grasped my revolver within the pocket of my greatcoat. I had just registered the hiss of a vesta being struck and caught a whiff of Holmes’s cigarette when muffled footsteps all at once thudded against the incline. I found that Holmes had chosen my hiding place with great care, for though I was concealed in the lee of the rock, a crack between it and the adjacent boulder afforded me a contracted view of the scene.

The Baron came into sight as he crested the ridge, perspiring visibly even in the frosty air, drawing his breath in great gasps. Glancing up into the woods before him, he stopped in horror and drew a pistol from his fur-lined cloak.

“Who goes there?” he demanded in a rasping voice.

“It is Sherlock Holmes, Lord Ramsden. It is imperative that I speak with you.”

“Sherlock Holmes!” he cried. “What are you doing about at this hour?”

“I might say the same to you, my lord.”

“It is hardly any business of yours,” the Baron retorted, but his words were brittle with panic. “I have paid a visit. A friend—”

Holmes sighed. “My lord, I cannot allow you to perjure yourself in this manner, for I know your errand tonight dealt not with the living but with the dead.”

“How could you know that?” asked the Baron.

“All is known to me, my lord.”

“So you have discovered her gravesite, then!” His hand wildly trembling, he waved his pistol at the ground in small circles as if unsure of its purpose.

“I paid it a brief visit this morning,” Holmes acknowledged gently. “I knew you, upon your own confession, to have loved Elenora Rowley. There you thought yourself wise, for you reasoned that too many trysts and too much correspondence had occurred between you for utter secrecy to be maintained after her death.”

“I did—and so I told you all!”

“From the instant your family realized the ring was missing, you have played the game masterfully,” Holmes continued, never moving his hypnotic grey eyes from the Baron’s face, though I knew his attention as well as my own was firmly fixed upon the pistol. “You summoned Dr. Watson and myself to aid the police; you even insisted we remain at Blackheath House until all was settled. I extend my compliments to your very workmanlike effort.”

The Baron’s eyes narrowed in fury. “I was forthright with you. I showed you and your friend every imaginable courtesy. So why, then, did you do it? Why would you ever have visited her grave?”

“For the very simple reason that you claimed not to know where it was.”

“Why should I have?” he demanded. “She was the entire world to me, yes, but—” He took a moment to master himself. “Our love was a jealously guarded secret, Mr. Holmes, and I abased myself once already by mentioning it to a hired detective.”

“Men of your station do not venture upon painful and intimate

subjects with strangers except out of dire necessity,” Holmes insisted. “You gambled that employing complete sincerity at our initial conference in London would terminate my interest. Your candour would indeed have bought you time enough to complete the affair had you been dealing with a lesser investigator. Even your tale of rebellious village boys vandalizing the grounds by night was a plausible fabrication. Much was revealed to me, however, by the condition of your clothes last Sunday evening.”

“I’ve told you already—my dog went after a pheasant and was caught in one of the villagers’ snares.”

“So I would have thought if your trousers alone had been muddied,” Holmes replied patiently. “But the soil was heaviest on the back of your forearms, just where a man rests his elbows to pull himself out of a hole in the ground nearly as high as he is himself.”

With a crazed look, Baron Ramsden leveled the pistol at Holmes, but my friend merely continued quietly.

“You loved Elenora Rowley with such a passion that you removed your grandmother’s wedding ring from the family vault, which you knew to be secure enough that it is scarcely ever inventoried. You then bestowed the gift on Miss Rowley, fully intending to marry a local merchant’s daughter whose beauty, or so I have been told, was matched only by her generosity of spirit.”

Here the Baron’s eyes dimmed and his head lowered imperceptibly, though the pistol remained trained on Holmes. “And so I would have done had she not been taken from me.”

“I had a long conversation with Miss Rowley’s former maidservant this morning. When Elenora Rowley fell ill, she sent you word she had departed with her parents to seek a cure on the Continent.”

“The specialists could do nothing,” the Baron acknowledged, his free fist clenched in his misery. “When she returned, the strain of travel had only hastened the course of her illness. She sent a note through the channels we’d created, telling me she loved me as she ever had—since we were both children and she the daughter of the

dry-goods supplier to our household. Within three days she—” A spasm seemed to shake him and he passed a hand over his brow. “Any fate would have been better. Even my own death.”

“Be that as it may, the lady died,” my friend replied compassionately, “and before it could occur to you in your grief that she had kept your token sewn into the lining of her garments, it had been buried with her. When you regained your senses, you realized, no doubt, that the heirloom had passed beyond your reach.”

“I was ill myself then. I was mad. For the better part of a month I was the merest shadow of the man I had been. I cared for nothing and no one,” the Baron stated numbly. “Yet my brother’s many follies follow each other like days upon a calendar, and our family is not as wealthy as my mother would have us suppose.”

“A matter of accounting, then, brought the missing jewel into the public eye.”

“I would never have taken it back from her else—in life or death. God help me! All the woes my brother has brought upon our heads are as nothing compared to my own. What will the appellation ‘grave robber’ do to the name of Ramsden?” he cried. Then, calming himself with all the reserve he could muster, Lord Ramsden drew himself up to his full height, his blue eyes glimmering eerily. “Perhaps nothing,” he continued, with a new and chilling precision to his speech. “Perhaps the only other person who knows of the matter will perish this very night.”

“It is not a very likely circumstance, is it, my lord?” my friend remarked evenly.

“So you may think,” his client snarled, “but you have underestimated my—”

“I am not so foolish as to have arranged this meeting in total solitude,” stated the detective. “My friend Dr. Watson has been good enough to accompany me.”

I emerged cautiously from behind the stony outcropping.

“So you have brought your spies!” cried the Baron. “You mean to ruin me!”

“You must believe, Lord Ramsden, that I have no intention of causing you the slightest harm,” Holmes protested. “My friend and I are prepared to swear that no word shall be breathed of this business to any living person, provided the ring is returned.”

“It is here.” The Baron placed his hand over his breast pocket. “But do you speak in earnest? It is incredible.”

“My little career would soon enough suffer shipwreck if I neglected my clients’ best interests,” my friend averred.

“Not the police, nor my family, nor any other person will ever hear of the matter now I have retrieved the ring? It is far more than I deserve.”

“They shall not on my account. I give you my word,” Holmes declared gravely.

“As do I,” I added.

“Then that is enough.” The Baron’s head fell forward as if in a daze, exhausted by his grief.

“It is not the first felony I have commuted, and I fear it is unlikely to be the last,” confessed my friend in the same calming tones.

“I shall be eternally grateful for your silence. Indeed, your discretion has been unimpeachable throughout this affair, which is far higher praise than I can apply to my own.”

“There I cannot agree with you,” Holmes began, but the Baron continued bitterly.

“Ellie died alone rather than betray my trust. What have I offered her in return?”

“Come, my lord. It is hardly practical to dwell on such matters. You acted in the interests of your family, and your secret is safe, after all.”

“No doubt you are right,” he whispered. “You may proceed to the house, gentlemen. It is over. I shall be more silent hereafter, you may trust.”