Duke (15 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

This may or may not be so, but it is true that Mills pulled the string that got Ellington into the Cotton Club. It was attached to Jimmy McHugh, who later composed such blue-chip standards as “I’m in the Mood for Love” and “On the Sunny Side of the Street.” McHugh started out writing and plugging songs with Mills, in due course becoming general manager of Jack Mills Inc. Unable to make it on Broadway, he took a shot at Harlem and started writing songs for the Cotton Club. Andy Preer, the leader of the house band, died in 1927, and McHugh saw in his death an opportunity to improve the quality of the club’s music: “I heard Duke and I wanted him. For one thing he and his boys could read [music]. The band I had to let go couldn’t. I had to sit down at the piano and play every tune for them until they learned it.”

All that was needed was to get Ellington out of a conflicting engagement, which was no trouble for a multiple murderer. One of Madden’s associates made Clarence Robinson, the producer of the Philadelphia show in which the band was appearing, an offer he couldn’t refuse: “Be big or you’ll be dead.” Two weeks later, on December 4, 1927, Ellington and his men opened at the Cotton Club. “Everybody was betting we wouldn’t last a month,” he said in 1940. They lasted for three years, and when they left to go on the road, their leader was on the verge of becoming a star.

• • •

Nineteen twenty-seven was a phenomenal year for American culture. It was the year of

Show Boat,

The General,

Elmer Gantry,

Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies,” Stuart Davis’s

Egg Beater No. 1,

Aaron Copland’s jazz-flavored

Piano Concerto,

and the last volume of H. L. Mencken’s

Prejudices

. Charles Lindbergh flew from New York to Paris in May, and Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in August. For those who knew how to make it, there was money to burn: Babe Ruth, who hit sixty home runs for the Yankees that year, was paid a yearly salary of $70,000, the equivalent of $857,000 today. (A laborer at Fisher Body’s assembly plant in Flint, Michigan, made $1,783.) You could buy a loaf of bread for nine cents, a copy of

Time

for fifteen cents, a raccoon coat for $40, an Atwater Kent radio for $70, or a Model T for $290. Radio was big, but the phonograph was bigger: One hundred million records were sold in America in 1927, and among them were Louis Armstrong’s “Potato Head Blues” and Bix Beiderbecke’s “Singin’ the Blues.”

The entertainment listings in the “Goings On About Town” section of the December 3 issue of

The New Yorker

read like a magic carpet ride. On Broadway Katharine Cornell was starring in Somerset Maugham’s

The Letter,

Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne in George Bernard Shaw’s

The Doctor’s Dilemma,

and Fred and Adele Astaire in George and Ira Gershwin’s

Funny Face

. If you felt like taking in a movie, you could check out

The Jazz Singer,

which had opened in October and was still going strong, though the magazine gave it a mixed notice: “Al Jolson superb in the Vitaphone which accompanies this dull movie.” Alfred Stieglitz was showing works by John Marin, America’s first cubist painter, at Room 303, the photographer’s modernism-friendly art gallery. Among the books reviewed in the magazine was Thornton Wilder’s

The Bridge of San Luis Rey,

and the list of recommended new titles for Christmas shoppers included Willa Cather’s

Death Comes for the Archbishop

and Ernest Hemingway’s

Men Without Women

.

“Goings On About Town,” however, had yet to come upon the Cotton Club. The only Harlem nightspots mentioned in the December 3 issue, and for many more issues to come, were Barron Wilkins’s Exclusive Club, Small’s Paradise, and Club Ebony. “The later the better, and do not dress,” the magazine advised readers interested in visiting Harlem. A week later Lois Long, the wife of high-society cartoonist Peter Arno (“We’re going to the Trans-Lux to hiss Roosevelt”) and the cabaret correspondent of

The New Yorker,

whose “Tables for Two” column she wrote under the fey pseudonym of “Lipstick,” announced, “I am mad at Harlem. It is getting too refined. All the Harlemites are getting a little ashamed of the Black Bottom, that quaint old native dance handed down by levee-working grandfathers. . . . Give me a Holy Rollers meeting any time. Or Small’s. Or, possibly, the Ebony.”

The New Yorker

had only just started covering “popular records” in 1927, and the unnamed critic who wrote about them seemed not to have heard any black musicians. (He favored Ben Bernie and the Clicquot Club Eskimos.) Indeed, one could read the magazine for month after month without running across a hint that black people of any kind existed, though a couple of weeks later a poetess named Frances Park opined on “Harlem 1927”: “A slim brown girl / With a heart of flame / Will never admit / She feels it shame / To be dark of skin / With ink-black hair, / Nor wish she were / As the white folk there.” But “Lipstick,” unlike her colleagues, knew her way around Harlem, and she also knew that certain of its nightspots were friendlier than others to visitors from downtown. In due course “Goings On About Town” advised its readers to stick to Connie’s Inn and Small’s unless you have “a friend who’ll personally conduct you.” Soon the advice was more direct: “Better find a friend who knows his way about; the liveliest places don’t welcome unknown whites.”

As for the Ellington band, it was already known throughout upper Manhattan. A reviewer for

The

New York Age

had written in October that “with the possible exception of Fletcher Henderson’s band, Duke Ellington seems to head the greatest existing aggregation of colored musicians.” But Ellington had to win the support of white journalists in order to make it big. Fortunately, Abel Green, who had been following the band since its Hollywood Café days, covered its Cotton Club debut for

Variety

. Green devoted most of his column to the “teasin’est torso tossing” of the “almost Caucasian-hued high yaller gals” of the chorus line: “Possessed of the native jazz heritage, their hotsy-totsy performance if working sans wraps could never be parred by a white gal.” But he also gave a nod to the musicians who backed them up: “In Duke Ellington’s dance band, Harlem has reclaimed its own after Times Square accepted them for several seasons at the Club Kentucky. Ellington’s jazzique is just too bad” (i.e., very good).

Some witnesses felt that the Ellington band wasn’t at its best that night. One of them was Irving Mills, who said years later that “the first show was kind of weak.” That stands to reason. Because the band was brought in at the last minute, Ellington didn’t have enough time to rehearse his men, and it wasn’t until he opened at the Cotton Club that the ten-piece instrumentation heard on his recordings became permanent. Prior to that time, the size of the group had fluctuated from gig to gig. Adding new players to so unified an ensemble at the last minute would have thrown the old ones off their game—though not for long. Ellington and the band played two floor shows a night, one at midnight and the other at two

A.M

., and they played for dancing before, between, and after the shows. The long hours that they spent on the bandstand evidently whipped them into shape, for the records that they cut for Victor on December 19 include a well-played version of “Harlem River Quiver,” a song written by McHugh and Dorothy Fields, his fresh-faced new lyricist, for the band’s first Cotton Club revue.

What else did the band play? This question is difficult to answer with exactitude. Ellington made studio recordings of a half dozen McHugh-Fields songs, most of which were written for Cotton Club shows, but little else is known about the other Ellington-penned numbers that were heard there. Surviving programs of the five shows seen at the club between 1927 and 1929 are insufficiently informative on this point, nor do newspaper reviews offer much more in the way of specific detail. No live recordings of the band were made during this period, and almost no contemporary manuscript material survives.

¶¶

It has long been taken for granted that many of Ellington’s compositions of the late twenties were written to accompany Cotton Club production numbers, and some scholars have suggested that the chance to write music for the club’s shows played a pivotal role in his development as a composer, but it wasn’t until 1930 that he wrote a score of his own. Prior to that time, McHugh and Fields wrote the songs. All that Ellington did was orchestrate them.

It’s possible that some of his instrumental compositions were used to accompany production numbers, but we cannot be sure.

Music Is My Mistress,

as usual, sheds little light on the subject: “The music for the shows was being written by Jimmy McHugh with lyrics by Dorothy Fields. . . . They wrote some wonderful material, but this was show music and mostly popular songs. Sometimes they would use numbers that I wrote, and it would be these we played between shows and on the [radio] broadcasts.” Barney Bigard, who joined the band after it opened at the Cotton Club, makes things marginally clearer: “We played two shows each night to accompany the chorus line or acts that they had. . . . We played for dancing in between. Some of the acts brought in their own music, but Duke wrote for a lot of them.” While this sounds plausible, Ellington identifies only one composition in

Music Is My Mistress,

“The Mystery Song,” that was written specifically to accompany a Cotton Club act. Hence it seems likely that when the band played his music at the club, it was usually for dancing by the customers.

We know even less about the shows themselves, which were staged by Dan Healy, a vaudevillian turned Broadway performer who had appeared in Irving Berlin’s

Yip Yip Yaphank

and the

Ziegfeld Follies of 1927

. Fields recalled that in addition to the songs that she and McHugh wrote for the club, the performers there interpolated other numbers that were among “the most shocking, ribald, bawdy, dirtiest songs anyone had ever heard in the 1920s,” though the surviving lyrics now seem tame: “Jelly roll, jelly roll, nice and brown / If you want my jelly roll, you’ve gotta come to town.”

***

Spike Hughes, however, agreed with Fields: “Every dance routine was too long and too loud, and after an hour of suggestive songs sung without charm or humour the discriminating customer could scream at the reluctance of the singers to say in plain language that fornication was fine, and leave it at that.” According to Healy, such songs were a must. “The chief ingredient [in the shows] was pace, pace, pace!” he said. “The show was generally built around types—the band, an eccentric dancer, a comedian . . . And we’d have a special singer who gave the customers the expected adult song in Harlem.”

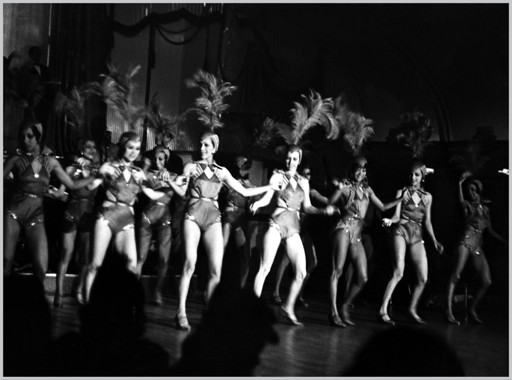

“Pace, pace, pace”: The frenzied climax of a Cotton Club floor show. Note the skimpy attire and “high yellow” complexions of the Cotton Club Girls, who were paid adequately and treated decently by the white gangsters who ran the club

That was all that Healy had to say about what happened onstage. In 1930 a British newsreel cameraman shot a minute-long sequence showing Ellington accompanying the chorus line in fragments of a lively finale-type production number, but contemporary reviews contain only sketchy descriptions of the routines, and the only detailed account that has come down to us is that of Marshall Stearns:

I recall one where a light-skinned and magnificently muscled Negro burst through a papier-mâché jungle onto the dance floor, clad only in an aviator’s helmet, goggles, and shorts. He had obviously been “forced down in darkest Africa,” and in the center of the floor he came upon a “white” goddess clad in long golden tresses and being worshipped by a circle of cringing “blacks.” Producing a bull whip from heaven knows where, the aviator rescued the blond and they did an erotic dance. In the background, Bubber Miley, Tricky Sam Nanton, and other members of the Ellington band growled, wheezed, and snorted obscenely.

This lurid description puts flesh on the memories of Howard “Stretch” Johnson, a high-minded Cotton Club tap dancer who later became a Communist Party organizer. For Johnson, Healy’s shows were “top-flight performances designed to appease the appetite for a certain type of black performance, the smiling black, the shuffling black, the black-faced black, the minstrel coon-show atmosphere which existed.” It was all part of the image of the club, one of whose programs was bedecked with a caricature of a grinning darky doorman bowing obsequiously to three white patrons in evening dress.

But Ellington and his sidemen were not coon-show clowns, nor did they think it demeaning to perform at a popular nightspot that paid each of them $75 a week, an annual salary of nearly $48,000 in today’s dollars, not counting tips, which were often considerable. According to Ellington, “It didn’t really matter what the salary was. A big bookmaker . . . would come in late and the first thing he’d do was change $20 into half dollars. Then he’d throw the whole thing at the feet of whoever was singing or playing or dancing. If you’ve ever heard $20 in halves land on a wooden floor you know what a wonderful sound it makes.” That was more than decent money for a man of any color in 1927, and Ellington himself took a pragmatic view of what he and his colleagues had to do to get it: “The girl you saw doing the squirmy dance . . . was not in the throes of passion. She was working to get that salary to take home and feed her baby, who sometimes lived pretty well.” Even Johnson saw the bandleader’s music as “a creative form of irony which masked the commercial pandering to an upper-class white audience thrilled at the opportunity to hear and witness what it thought was genuine black exotica.”