Drinking Water (23 page)

As a society, we clearly have deeply conflicting feelings about bottled water. As the story of McCloud in the introduction made clear, there are deep divisions within society over whether our relationship with drinking water should be based on the market or considered a human right. Nowhere is this starker than with bottled water. What explains its remarkable ascent not only to market dominance but to cultural dominance, as well, where bottled water is now taken for granted as the

primary

way to drink water? Is it really better for us than tap water?

These are current questions, but the answers lie many years back, for the story of bottled water is older than the introduction of Perrier a few decades ago—far older, and much more surprising.

T

HE NEED FOR BOTTLED WATER GOES BACK TO THE VERY FIRST SOCIETIES

. Whether in goatskins, gourds, or clay pots, hunters and groups on the move needed containers to transport water with them, particularly if they were unsure where the next source of safe water might lie. There is no evidence, however, of a true market for bottled water in ancient times, in the sense of containers of water sold for consumption somewhere else. Instead, local water needs were satisfied by water sellers who provided a drink or filled containers brought by customers.

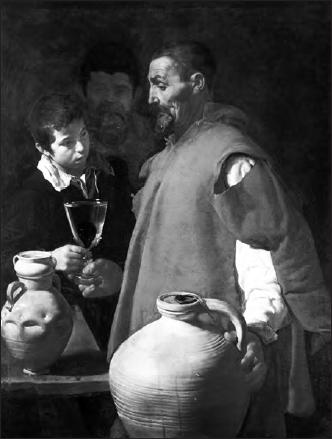

The famous seventeenth-century painting by Velázquez of a water seller in Seville suggests the human precursor of the modern vending machine

.

The origins of bottled water markets lie not with water sellers, however, but with an entirely different and unexpected source: the veneration of spring waters thousands of years ago. After all, what could be more mysterious to premodern people than a natural spring? How the water came to the surface, literally flowing out of rock, could not be easily explained, much less the mysterious minerals, carbonation, heat, and smells of the strange waters. How else to explain these but by mystic origins? No surprise that springs and wells were often explained by a divine presence, by local gods who looked after the waters, sometimes for good and sometimes for ill.

From earliest times, natural water sources have been linked with mystical healing and divine powers. The Bible is filled with references to particular wells. Other regions, such as the Scottish Isles, have long boasted their own special waters. As recounted earlier, in Scotland in the Middle Ages, those suffering from insanity were cured by drinking at St. Maelrubha’s Well, while those suffering from toothaches could seek relief by drinking from the healing well on the isle of North Uist.

Similar stories from around the world speak of waters with miraculous healing powers. According to local legend, different wells could cure the sick or restore movement to the lame, eyesight to the blind, and fertility to the barren, not to mention provide relief from rickets, lameness, whooping cough, leprosy, paralysis, etc. These cures may sound ridiculous to modern ears. Spring waters, though, really can have curative powers. Like Coke, some of these waters are the Real Thing.

There is no such thing as pure water in nature. Lots of substances, both organic and inorganic, like to dissolve in water. All spring water starts originally as rain or snow falling to the ground. Water’s particular nature comes from both the downward path it takes as it seeps through the earth and its upward path as it slowly ascends through geologic layers, emerging at a different point. As with all journeys in life, the nature of the passage makes all the difference. Water passing through limestone will be higher in dissolved calcium and magnesium. Water filtering through igneous

rocks will pick up dissolved sodium in its slow years-long migration returning to the surface.

While it may sound pretentious to compare water to wine, it’s a fair analogy. Just as wine grapes are flavored by their vines’ soil, so, too, does mineral water gain its chemical composition through the rock strata it has passed. The precise composition of the water—its

terroir

, if you will—depends on the local geology, and, it turns out, so does the water’s therapeutic value.

Modern medicine has demonstrated that natural salts can soothe the pains of arthritis. Sulfates and bicarbonates found in some spring waters are routinely used to treat gastrointestinal ailments. Calcium strengthens bones and teeth. And water containing naturally dissolved lithium, a drug long used to treat depression, may even be useful for those with mental health problems. Thanks to their dissolved minerals, some healing waters really

do

heal beyond the power of positive suggestion.

In the era before modern medicine, and even today in some regions, these mineral-bearing waters were particularly important to health. Because of their unique natural composition of salts and minerals, many spring waters became widely known for their curative powers. Specific waters were recommended for specific ailments. Julius Caesar favored the hot waters at Vichy in France, known in Roman times as the Hot Town (Vicus Calidus). The great Renaissance artist Michelangelo suffered from kidney stones. His doctor ordered him to take the waters from a nearby town, and Michelangelo reported, “I am much better than I have been. Morning and evening I have been drinking the water from a spring about forty miles from Rome, which breaks up the stone. … I have had to lay in a supply at home and cannot drink or cook with anything else.” The German Romantic author Goethe swore by Fachingen waters near Wiesbaden with their high bicarbonate content. He wrote his daughter-in-law that the “the next four weeks are supposed to work wonders. For this purpose, I hope to be favored with Fachingen water and white wine, the one to liberate the genius, the other to inspire it.”

While we now understand the chemistry behind the curative powers of sacred springs, people at the time obviously looked to different explanations. In a society with no understanding of geology or modern disease, there was a need to attribute some cause to these waters’ origins and medicinal benefits. Attributing divine creation and curative powers to springs made sense from both a physical and metaphysical view. Thus did waters become sacred and imbued with special powers because of their mystic origins. These holy waters married the myth to the real, and their reputations endured over time.

Despite particular springs gaining notoriety for their curative powers, visits to distant springs for health were quite uncommon. Prior to the eighteenth century, traveling in Europe purely for health reasons was simply too expensive and often too dangerous. Yet people still traveled great distances to visit wells and springs, indeed large numbers of people. They traveled not for physical but for spiritual health. Particularly during the Middle Ages, pilgrimage routes were popular throughout Europe. Some, as Chaucer recounted, led to great cathedrals such as Canterbury; others led as far as Jerusalem. Near or far, however, many led to holy waters.

Most springs’ creation myths involved a miracle of some sort. To entrepreneurial Church officials, this created an intriguing business opportunity. Indeed, a number of holy wells began to compete with one another for the burgeoning commerce of pilgrims and holy objects. In a precursor to modern travel websites extolling white beaches, bronzed bodies, and pulsing nightlife, boosters of holy wells entered into an arms race of hyperbole. A comprehensive history of ancient wells relates, for example, how a monk of Winchecombe Abbey in Gloucestershire:

invented a story that Prince Kenelm of Mercia was murdered by his sister Quendreda’s lover, who buried Kenelm’s head under a thorn tree. A white dove carried a scroll that described the evil deed to the Pope in Rome, who ordered the body be found. Local

clerics used a white cow to locate it on the slopes of Sudely Hill, where a spring burst forth. Quendreda tried to curse the ensuing funeral procession by reading Psalm 108 backwards, but her eyes exploded. On the strength of this amazing tale, Winchcombe Abbey became a popular destination for pilgrims and one of the largest abbeys in England.

This incredible—truly incredible—tale invented at Winchcombe Abbey was a likely result of such boosterism, as pilgrimage sites competed with one another to get a cut from the revenue stream. One can just imagine the enterprising pilgrimage marketing materials. “You think going on pilgrimage to St. Maelrubha’s Well is holy? Just listen to what happened at Winchcombe Abbey! Exploding eyeballs!”

The intense interest in visiting such holy places and offering contributions created a sizable stream of revenue to Church coffers. In fact, the Church often had well-managed staff in place precisely to gather the pilgrims’ offerings. Holy wells had strongboxes strategically located to accept donations, and priests collected the daily inflow. The take could be huge.

The Church was not entirely corrupt, of course, and men of good faith were troubled by this practice. Thus one can find a series of canons and laws from the period that forbade pilgrims to travel to wells and holy water sites or to worship there. King Egbert declared in the ninth century, “If any keep his wake at any wells, or at any other created things except at God’s church, let him fast three years, the first on bread and water, and the other two, on Wednesdays and Fridays, on bread and water; and on the other days let him eat his meat, but without flesh.” The Bishop of Lincoln actually threatened to excommunicate pilgrims journeying to holy wells in Buckinghamshire. These paternalistic efforts to protect pilgrims and their money seem to have had little effect. The allure of holy wells and their sacred waters was just too strong.

So how do these stories of holy waters and pilgrims explain the rise of bottled water?

A sketch of water bottles with their distinctive seals from St. Menas’s holy well in Egypt

Pilgrims that chose to visit a famous well or spring faced a problem. While drinking or being blessed with the holy waters was all well and good, many wanted to bring some of the waters back with them. There was, after all, a booming trade in holy relics at the time. But how could pilgrims prove that the water they carried was really filled with holy waters? Just as a skeptical neighbor might cast doubt on whether a pilgrim had returned from Jerusalem with a piece of the True Cross, so, too, might he question whether the water the pilgrim carried was from distant Winchcombe Abbey or the nearby stream. “You say that’s holy water? Prove it!” The ingenious solution to this challenge provides the first example of bottled water marketing.

To validate pilgrims’ claims of authenticity, each holy well produced its own special flask that could only be obtained at that particular site. Every site had its own ceramics works, producing its own distinctive container with a special seal. These represent the earliest known case of water branding through packaging—a full fifteen hundred years before Perrier’s distinctively shaped green bottle.

While the market for bottled waters originated in the holy

relics trade, it was concerns over physical rather than spiritual health that transformed the market into what we see today. Starting in the eighteenth century, spas became the vacation spot to go and to be seen, both in America and Europe. As described above, the chemical content of mineral waters often provided real medical benefits. Contrexéville in France was renowned for its water’s powers in breaking up kidney stones and curing urinary complaints. Ferrarelle in Italy, described by Pliny the Elder as “miraculous waters” in his

Natural History

, was known to soothe digestive complaints. Évian-les-Bains near Switzerland was effective against skin diseases. Other spas’ waters were recommended for sufferers of arthritis, confusion, and an impressive range of ailments.

Clever entrepreneurs transformed the towns around the waters into destination sites themselves. The best-known spa town of all, the aptly named Bath in England, had been a popular site since Roman times. With hot mineral springs supplied by virtue of an underground volcanic fault, the Romans constructed a temple to Minerva and the English crowned King Edgar beside the springs in 973. By the eighteenth century, Bath had become a fixture in the aristocracy’s social calendar. During “The Season,” the great and the good would venture to Bath and revel in the balls, gambling, and promenades, all the while “taking the waters”—the convenient excuse for being there in the first place. This involved not only drinking the mineral waters but bathing in them, as well. Christopher Anstey described in 1766 the fully clothed men and women in what must have been a peculiar stately promenade in the steaming spa waters: