Drinking Water (14 page)

Inscriptions of water treatment devices have even been found in the tombs of the Egyptian pharaohs Amenophis II and Rameses II

.

In the late 1890s, for example, Pittsburgh’s city government considered plans to pass its water supply through a sand filtration system. This was strongly opposed by Edward Bigelow, director of the city’s public works department, who argued that “the city’s water did not cause typhoid and warned that impugning its quality would discourage investment in the city.” Nor was he alone in his concern about bad press. Philadelphia’s city council raised identical concerns over hurting the city’s image if its water were filtered.

The most significant development in drinking water treatment occurred at the turn of the twentieth century, with the realization that adding low concentrations of chlorine to water would kill most of the microorganisms. Prior to that time, no municipalities had ever added chemicals to their drinking water supplies. The technical challenge lay in delivery, how best to mix reactive chlorine into large amounts of water. The town of Middelkerke, Belgium, installed the first chlorine disinfection system in 1902. Jersey City

took the lead in the United States, providing in 1908 the first chlorination of drinking water for an entire city.

Easy to apply, inexpensive, and persistent in the water, chlorination gradually took hold. The adoption of chlorinated water was accelerated by the U.S. Department of the Treasury, which appointed a commission in 1913 to establish the nation’s first drinking water standards. While these standards were binding only on common carriers involved in interstate commerce (particularly trains), they had a widespread and immediate impact. Since water was taken on at local depots along the rail lines, national standards indirectly forced all communities providing water to common carriers to chlorinate their water, as well. By 1941, 85 percent of the country’s more than five thousand water treatment systems chlorinated their drinking water.

The widespread adoption of chlorinated drinking water had two immediate effects. The first was in the marketplace, where the bottled water sector collapsed. We tend to think of bottled water as a recent market entry, but it was big business at the turn of the twentieth century. With Philadelphia and other cities’ provision of chlorinated public water, however, the prime reason for buying bottled water in the first place—safety—was no longer relevant. And the chic branding that bottled water might have enjoyed was swamped by the appeal of chlorinated water. More than just a novelty, chlorinated water meant that water for an entire city could be made safe because of human ingenuity. In an age of technological optimism, municipal chlorination was a heady achievement. It was trendy, “modern” water. It is hard not to appreciate the irony of how this has reversed today, where tap water is seen as pedestrian and bottled water chic.

The second impact was on public health. The age-old scourges of waterborne disease—typhoid and cholera—had finally been neutered. Both pathogens, deadly and easily spread by water, were acutely vulnerable to low levels of chlorine. Typhoid epidemics were still killing thousands of Americans in the 1920s, but by the 1950s, even individual cases of typhoid had become rare. It has been claimed that chlorination of drinking water saved more lives

than any other technological advance in the history of public health.

In retrospect, chlorinating drinking water supplies seems an obvious decision. At the time, though, it was highly controversial. Despite high incidences of waterborne disease, drinking water was still generally regarded as safe. Adding a chemical to water to make it safer had never been done before on a large scale, and it seemed to many

unnatural

—to use a term with particular resonance in the bottled water market today. A pro-chlorine writer in 1918 summarized the many complaints against chlorination:

The nature of the complaints against chlorinated water is very diversified and includes imparting foreign tastes and odours, causing colic, killing fish and birds, the extraction of abnormal amounts of tannin from tea, the destruction of plants and flowers, the corrosion of water pipes, and that horses and other animals refuse to drink it.

In fact, in 1911, the Jersey City government refused to pay its innovative water supplier, the East Jersey Water Company. The company had signed a contract with the city committing to provide pure and wholesome water. It built a treatment plant for chlorination. Jersey City argued that the water also needed to be free from upstream sewage and therefore filtered. The company responded that its contractual obligation was to provide safe drinking water, which chlorination assured. Expensive filtration was therefore unnecessary. The dispute between old and new visions of water treatment eventually went to court. The judge sided with progress and chlorination, concluding that “the device for removing dangerous germs, now in operation, is effective and capable of rendering the water delivered to Jersey City pure and wholesome for the purposes for which it was intended.” The

New York Times

article reporting the decision proved remarkably prophetic, predicting, “So successful has been this experiment that any municipal water plant, no matter how large, can be made as pure as mountain spring water.” A century old, its appeal to the purity of natural spring waters almost reads like an ad for bottled water today.

Water can be made safe to drink, but it still needs to be moved to its final point of use. During this journey, water can be contaminated once again, frustrating the earlier efforts. Distribution, then, warrants just as much attention as source protection and treatment.

Water Distribution

In 701 BC, the Assyrian king Sennacherib had assembled a vast army and was imposing his empire’s might on the Kingdom of Judah. Judah’s fortified cities fell one after the other. Jerusalem was now in the conqueror’s sights. Hezekiah, the king of Judah, was determined that his capital would not fall to Sennacherib’s assault. While his kingdom’s cities were captured and plundered, Hezekiah busily prepared Jerusalem to withstand the coming siege. According to the biblical account, “he took courage, and built up all the wall that was broken down, and raised it up to the towers, and another wall without, and strengthened Millo in the city of David, and made weapons and shields in abundance.”

Hezekiah realized, however, that fortifying walls and towers would be futile if the city ran out of water. The problem was that the Gihon Spring, Jerusalem’s main source of drinking water, was located in a cave outside the city walls. Without water, a siege of just a few weeks might prove more effective than any armed assault by Sennacherib’s forces.

Hezekiah’s solution was simple in concept but fiendishly difficult in execution. Working round the clock, workers rushed to dig a tunnel through the local limestone, diverting water from the Gihon Spring to a well within the city walls. If done properly, this would not only provide water to the besieged population but also divert the water from the spring—denying it to the Assyrians.

To ensure completion before the Assyrian army arrived, digging started both near the Gihon Spring and within Jerusalem. The hope was that the two parties of miners would meet halfway along the five hundred meters separating their starting points. The problem, of course, was that both parties were deep underground, encased in rock. There was no obvious way to guide their respective paths, and an error of just a few meters would result in their blindly passing

one another, dooming the city. Against all odds, they succeeded in time, solving the problem of water distribution with the sword hanging over their heads. As the Bible recounts:

And when Hezekiah saw that Sennacherib was come, and that he was purposed to fight against Jerusalem, he took counsel with his princes and his mighty men to stop the waters of the fountains which were without the city; and they helped him. So there was gathered much people together and they stopped all the fountains, and the brook that flowed through the midst of the land, saying: “Why should the kings of Assyria come, and find much water?”

How the two groups of miners met each other remains a subject of archeological debate. Tourists today can slosh through the dark, winding 533-meter path, with dead ends and false starts clearly evident. One possibility is that the tunnel engineers simply widened a natural karst formation—essentially a preexisting fissure running through the rock. Another possible solution is that the tunnelers were guided through acoustic communication from a team on the surface. No one really knows for sure.

Whether Hezekiah’s efforts to withstand the siege were successful depends on which history you consult. Hezekiah did pay three hundred talents of silver and thirty talents of gold in tribute to Sennacherib, upon which the Assyrian king reportedly boasted “I ruined the wide province of the land of Judah. On Hezekiah, its king, I imposed my yoke.” According to the Hebrew biblical account, however, “the Lord sent an angel, who cut off all the mighty men of valor, and the leaders and captains, in the camp of the king of Assyria. So he returned with shame of face to his own land. And when he was come into the house of his god, they that came forth of his own bowels slew him there with the sword.”

The challenge of distribution, of moving safe water from its source of origin to final consumption, is unavoidable. Throughout most of human history and for much of the world today, water distribution has meant manual labor: walking to the water source and filling a gourd, leather sack, clay pot, bucket, or jerry can with water

and then carrying it back to the home. Water is heavy—more than eight pounds for a gallon of water—so water that has to be transported a distance exacts a real cost in time and labor.

Piped water largely avoids this problem. We have already discussed the graceful aqueducts of the Roman Empire, many of which stand today, but irrigation channels, canals, and pipes have been the hallmark of most enduring civilizations. Subject to the unyielding force of gravity, engineers have needed to rely on clever solutions that ensure a downward gradient from source to collection.

As cities grew in size, the importance of the distribution system also grew since the nearby water sources became polluted over time. This continued well into the Middle Ages. The Great Conduit of London was built in the thirteenth century between London and the springs at Tyburn. Water was transported to cisterns in the city, and the water then sold by leasing official mugs to people for drawing water. One can find impressive technology in some monasteries as well. Indeed, the cities of Southampton and Bristol contracted with their local monasteries to use their more advanced water systems.

N

O DISCUSSION OF MODERN WATER DISTRIBUTION WOULD BE

complete without describing the rise of the drinking fountain. The ancient precursors to the modern drinking fountain were the village wells,

lacus

, or fountains where people would either bring their own containers or share a communal cup to slake their thirst. As cities became more and more crowded and polluted during the industrial revolution, finding safe drinking water became increasingly difficult. As

Punch

magazine explained in its description of the Great Exhibition in 1851, “Whoever can produce in London a glass of water fit to drink will contribute the best and most universally useful article in the whole exhibition.”

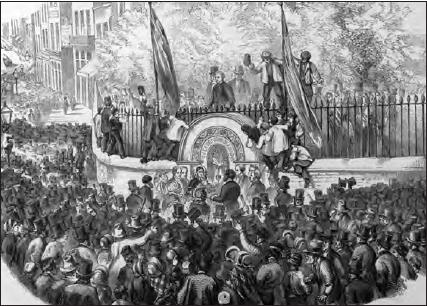

Given the foul state of easily accessible water, drinks from pubs provided the easiest accessible beverages. Thus it is no coincidence that the Quakers, a Christian denomination that abstained from alcohol, founded in 1859 the Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association—a philanthropic society that built free public fountains

around London. The motivation was twofold, in part a public service for those too poor to purchase drinking water, and in large part a strategy of the temperance movement. Many of the fountains were strategically located next to popular pubs, tempting thirsty souls with free, safe, and wholesome water rather than the purchase of sinful beer or spirits.

The Free Drinking Water Association gained immediate support from establishment figures such as Prince Albert and the Archbishop of Canterbury. As the resolution adopted at the inaugural meeting made clear, this was to be a venture dedicated to the common good. The resolution declared:

That, where the erection of free drinking fountains, yielding pure cold water, would confer a boon on all classes, and especially the poor, an Association be formed for erecting and promoting the erection of such fountains in the Metropolis, to be styled “The Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association”, and that contributions be received for the purposes of the Association. That no fountain be erected or promoted by the Association which shall not be so constructed as to ensure by filters, or other suitable means, the perfect purity and coldness of the water.

The association built its first fountain soon after on the wall of St. Sepulchre’s church. This was recognized at the time as such a historic event that a banner reading “

THE FIRST PUBLIC DRINKING FOUNTAIN

” was chiseled into the stone and a celebration was held with formal speeches.

Excitement over the first fountain carried over well into the next decade, with funds pouring in. As noted above, the association sought to provide safe water for free to the poor, and this often competed with pubs. To attract customers, a number of pubs also provided water troughs, enticing people to buy a drink inside while their horses drank outside. Sensitive to the thirst of animals and the temptation of pubs’ alcohol, the association changed its name to the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association. Within eleven years of its founding, there were 140 fountains and 153 cattle troughs available to the public for free use throughout London.