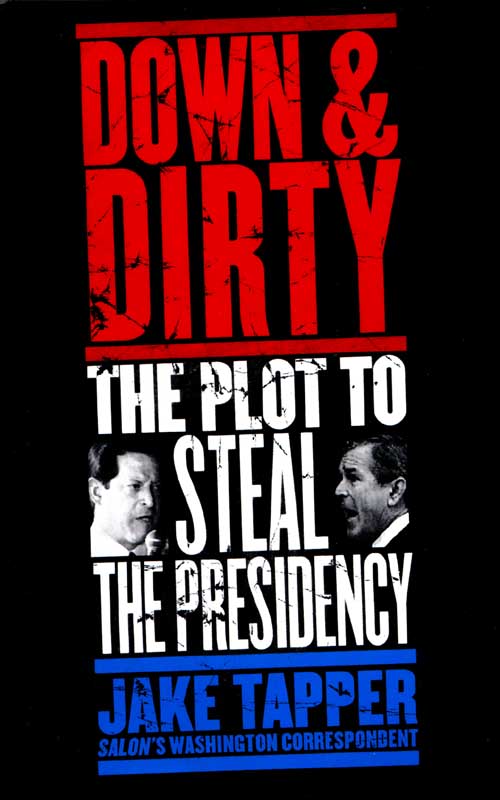

Down & Dirty

Authors: Jake Tapper

Copyright © 2001 by Jake Tapper

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including

information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may

quote brief passages in a review.

The map on

page 2

appears courtesy of Time Inc. The butterfly ballot,

page 18

, and chad diagram,

page 118

, appear courtesy

© 2000 Sun-Sentinel Company.

Excerpts from John DiIulio’s essay “Equal Protection Run Amok” originally published in

The Weekly Standard

of December 25, 2000, appear courtesy of Mr. DiIulio and

The Weekly Standard,

copyright 2000 News America, Inc. Excerpts from

The Recount Primer

appear courtesy of Jack Young.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: March 2010

ISBN: 978-0-7595-2318-0

Contents

Chapter 1: “Do you get the feeling that‘Florida might be important‘in this election?”

Chapter 2: “You don’t have to be snippy about it.”

Chapter 3: “Do you remember us hitting anything?”

Chapter 4: “Palm Beach County is a Pat Buchanan stronghold.”

Chapter 5: “That limp-dicked motherfucker.”

Chapter 6: “You fucking sandbagged me.”

Chapter 8: “I’m willing to go to jail.”

Chapter 9: “We need to write something down.”

Chapter 10: “You know what I dreamed of today?”

Chapter 12: “ARREST HIM! ARREST HIM!”

Chapter 14: “This has to be the most important thing.”

Chapter 15: “Like getting nibbled to death by a duck.”

Chapter 16: “We’re going to massacre them.”

Chapter 17: “You were relying on the Gore legal team to give you the straight facts, weren’t you?”

Chapter 18: Subject: gore clean up

Chapter 19: “A little matter down the road.”

Chapter 20: “Boy, that was some Election Night, huh?”

To Dad

U

sually when Americans go to Florida for a spell, they come back looking better—tan, refreshed, relaxed, a few piña coladas

under their belt.

It didn’t quite work out that way for America as a whole.

America is the greatest country in the history of the world, and the fact that we had a peaceful transfer of power even after

everything that went down from November 7 through December 13, 2000, is a testament to that fact. But what happened in Florida

brought out the ugliest side of every party in American politics, as if the state became a fun-house mirror with harsh lighting,

magnifying the nation’s blemishes and cellulite.

Democrats were capricious, whiny, wimpy, and astoundingly incompetent. Republicans were cruel, presumptuous, indifferent,

and disingenuous. Both were hypocritical—appallingly so, at times. Both sides lied. Over and over and over. Far too many members

of the media were sloppy, lazy, and out of touch. Hired-gun lawyers pursued their task of victory, not justice. The American

electoral system was revealed to be full of giant holes.

The people themselves were split into three groups: Those who cared so much about their candidate winning they lost all sense

of reason, consistency, or civility. Those who were so apathetic they couldn’t care one way or another, they just wanted it

to be over. And people like you, gentle reader, who fell somewhere in between.

In many ways, Florida was the perfect setting for the freak show. Long before Vice President Al Gore and Gov. George W. Bush

began battling over Florida—pouring millions of dollars and days and days in campaign stops in pursuit of its 25 electoral

votes—the area currently known as the Sunshine State was ground zero for the eighteenth-century struggle for domination over

the New World. With Britain, France, and Spain tripping over one another in the northern end of the state—Britain in Georgia, France

in Louisiana, and Spain in Florida—the three superpowers constantly squared off against one another.

Gore isn’t even the first to refuse to concede Florida in the face of crushing evidence to the contrary. When Seminole chief

Billy Bowlegs surrendered after the Third Seminole War, going west in 1858 with about one hundred of his fellow Native Americans,

more than three times that number remained in the Everglades. The Seminole tribe never officially conceded, remaining to this

day in a declared state of war with the United States. Even Gore didn’t prove that tenacious.

What happened in Florida was the perfect ending to campaign 2000. Gore was an uninspiring technocrat politician—cold and ruthless— who

constantly sold out his friends, staffers, and values in his pursuit of power. So anemic were his campaign and communication

skills, so apparent and easily exploitable were his vulnerabilities (especially his tendency for puffery), he couldn’t manage

that last final step to the crown that he had been groomed from the crib to assume. His three debate performances were so

different in tempo and temperature, it was as if he hadn’t spent his entire adult life in the public eye. More important,

the multiple personality disorder seemed to symbolize the larger problem of a man who didn’t really know who he was.

The Republicans caricatured him as one who would do anything to get elected, but Gore happily handed them the Magic Markers.

And while Gore’s lack of an inner core—behind closed doors as vice president, he reportedly argued with other Clinton advisers

against affirmative action, while he tried to slam Bush for opposing it during presidential debates— may have created no more

than an uneasiness among middle-of-the-road undecided voters, it had disastrous consequences in his party’s white left wing.

After the campaign-finance abuses of the Clinton-Gore 1996 reelection campaign and his administration’s actions on trade agreements like

NAFTA and GATT, Gore’s protestations to be a fighter for the little guy rang so hollow that 2,878,000 lefty and disillusioned

Americans voted for Ralph Nader—including almost 100,000 Floridians.

Bush, conversely, was a brilliant schmoozer and deft liar, but he had the intellectual inquisitiveness of your average fern.

Not only did the Yale grad actually utter the word “subliminable”—not once but twice—but in the closing months of the presidential

race he was still expressing ignorance about federal institutions, like the Food and Drug Administration, laws, like the Employment

Non-Discrimination Act, and long-passed bills, like the Violence Against Women Act, through which $50 million had been given

to his state’s budget during his tenure. He do-si-do’ed his way to the White House with little to recommend him but a fratty

charm that wore

thin quick. It was barely enough to recommend him for president of DKE, much less commander of the known universe. More darkly,

during his South Carolina primary campaign against Arizona senator John McCain, Bush seemed more than willing to cozy up to

the eviler forces in his party. His first stop in the Palmetto State: fundamentalist Bob Jones University, where anti-Catholic

dogma is the norm, and interracial dating was banned until 2000. McCain and his family were attacked ruthlessly, disingenuously, by

Bush and his forces and their allies. Once, after I wrote a story criticizing Bush for “the race-, gay-, and Jew-baiting campaign

that he and his allies waged in South Carolina,” a senior Bush staffer called me to angrily complain. “Where was the Jew-baiting?!”

*

he asked, not even remotely understanding the pathetic hilarity underlying his selective defensiveness.

Both candidates were wanting. After the first presidential debate, I wrote that “Gore’s still unlikable, Bush still seems

dumb. Feels like a tie.” And that pretty much summed up the whole shebang. Neither man deserved it. Neither man captured the

hopes of the nation as had, say, Ronald Reagan in 1980.

So it was only fitting that both Gore and Bush were forced to continue their respectively unconvincing pitches for the White

House for more than a month after the race was supposed to have ended. Neither of them had proved worthy of the job to begin

with, and neither deserved to win as desired a prize as others had. They needed to fight for it even more, and more desperately,

and whoever ended up winning it needed the position deflated.

When it became clear in 1961 that New York Yankee Roger Maris might well break the revered Babe Ruth’s sixty-home-run record,

commissioner of baseball Ford Frick made a ruling that would forever sully Maris’s achievement. Frick ruled that since the

Babe’s record was set in 1927, when seasons lasted 154 games, Maris would have to break the record in the exact same number

of games. Maris broke the record, hitting sixty-one homers,

but, because the baseball season in 1961 consisted of 162 games, an asterisk stained his appearance in the record books until

1992, when Frick’s ruling was scrapped. Of course, by then Maris had been dead for seven years.

Far more so than in the case of Maris, between Gore and Bush it wasn’t tough to argue that whoever ended up winning the presidency

needed to have, forever more, an asterisk next to his name.

And one big mother of an asterisk President Bush did get. We will never know who would have won Florida had all the ballots

been hand-counted by their respective canvassing boards. Adding to the confusion were thousands of trashed or miscast ballots—including

Palm Beach County’s infamous “butterfly ballot.” We will never know who, therefore, truly was the choice of the most Floridians

and who, therefore, really earned the state’s critical electoral votes and therefore the presidency. That Gore ended up winning

more than a half million popular votes over Bush complicated matters. Of course, had Gore been the one who successfully engineered

a victory, there would have been innumerable reasons why he, too, was undeserving. Perhaps reasons even greater than Bush’s.

How the figurative asterisk came to pop up next to Bush’s name is a fascinating tale, both for lofty, academic reasons—for

what it says about our republic—as well as for the sheer insanity of it all. I spent two years, 1999 and 2000, following Bush

and Gore around, and most of the thirty-six days following the November 7 Election Day in Florida, watching in horror and amusement—mostly

amusement—the circus. I spent the following months tracking down the players who briefly appeared on our TV screens and catching

up on what the rest of us who weren’t in their shoes missed. The following is what I saw and what I learned from the players

after it was all over.

About the research methods for the book.

Quotes are taken directly from transcripts, reconstructed by one or more of the players in the conversation, or—where noted—from

specific media stories. Thoughts attributed to an individual come from an interview with that individual.