Dorset Murders (25 page)

âI'VE BEEN A GOOD WIFE TO HIM AND NOBODY CAN SAY I HAVEN'T'

N

ineteen-year-old Charlotte McHugh, an illiterate Irish gypsy girl, once believed that she had found her prince charming in the form of an English soldier. Frederick John Bryant was a military policeman serving with the Dorset regiment and met Charlotte when he was sent to Londonderry, one of 60,000 English soldiers dispatched to assist in the repression of the Sinn Fein movement during the Irish troubles of 1917â22.

When Bryant left Ireland to return to civilian life and his job as a cowman in Dorset, Charlotte went with him. The couple married in March 1922 at Wells in Somerset, and settled in a tied cottage at Nether Compton, near Sherborne.

However, life in rural Dorset wasn't the idyll of Charlotte's dreams. She had simply exchanged poverty and squalor in Ireland for the same in England. Frequently, she sought relief from her desperate circumstances by visiting the local pub, where she became known amongst the locals as âCompton Liz', âBlack Bess' or âKillarney Kate'. As well as gaining several nicknames, Charlotte also gained a reputation for accepting drinks from strange men, many of whom were subsequently invited back to the cottage she shared with Frederick.

Not only were these liaisons extremely pleasurable for Charlotte, but they were also a means of supplementing the meagre 38

s

her husband received as his weekly wage. Bryant was well aware of his wife's extra-marital activities and even condoned them. âI don't care what she does', he told a neighbour who had informed him of Charlotte's visitors. âFour pounds a week is better than thirty bob.'

Charlotte had pretensions to an extravagant lifestyle. On occasions, she was known to buy luxury foodstuffs and she also sometimes hired a car and driver for a day, the cost of which was almost the equivalent of a week's wage for her husband. To support her aspirations, Charlotte became adept at thinking of new ways to extract money from her gentleman callers. On one occasion, she managed to convince a Yeovil businessman that she was carrying his baby. The man â doubtless terrified of the likely scandal â quickly handed over £25 to pay for an abortion but, months later, Charlotte returned with a baby in her arms, demanding regular child support payments. In fact, the baby was fathered by neither the businessman nor Charlotte's husband, but was the progeny of one of her most regular lovers, Leonard Parsons.

Parsons â or Bill Moss as he was sometimes known â was a travelling salesman and horse dealer with a gypsy background and nomadic lifestyle similar to Charlotte's own. Moss lived with Priscilla Loveridge on Huish gypsy camp at Weston-super-Mare. Together they had four illegitimate children. However, once he met Charlotte and became her lover in 1933, Parsons all but moved in with the Bryant family. Surprisingly under the circumstances, he and Frederick Bryant became good friends, often drinking together at the Crown public house and even sharing a razor.

It was while Parsons was staying at the cottage that Fred Bryant suffered the first episode of what was to become a prolonged illness. On 13 May Bryant went to work as usual, while Parsons left to conduct some business, taking with him Charlotte and Ernest, the Bryant's oldest child. Fred ate the lunch of meat, potatoes and peas left for him by Charlotte and, shortly afterwards, became seriously ill with what looked like food poisoning.

Weakened by severe vomiting and diarrhoea, all Fred could do was to call out for his next-door neighbour, Mrs Ethel Staunton. When Mrs Staunton heard his cries, she immediately went to see if she could help, finding Fred sitting on the stairs, groaning and shivering violently. Fred asked her to fetch a tin bath from the garden, which she did, making him a solution of salt water to induce vomiting. She then went off to fetch her husband, Bernard.

By the time she came back, Frederick Bryant had managed to drag himself upstairs to bed. He had also vomited into the bath, bringing up a large quantity of what Mr Staunton described as âgreen frothy stuff'. Staunton sent someone to telephone for the doctor and, while waiting for him to arrive, made up several hot water bottles for his neighbour who was complaining of feeling bitterly cold.

Dr McCarthy eventually arrived to find Frederick Bryant complaining of stomach pains and cramp in his legs and suffering from bouts of severe sickness and diarrhoea. Concluding that his patient had an attack of food poisoning, he gave him an injection and left him to rest. When he called back at the cottage the next day, he found Bryant's condition to have greatly improved. Charlotte Bryant was attending to him and McCarthy questioned her about what her husband had eaten over the previous couple of days. Charlotte assured him that Fred had eaten exactly the same food as the rest of the family and that nobody else had suffered any ill effects, which appeared to rule out food poisoning as the cause of Fred's illness.

Fred eventually made a full recovery but, on 6 August, he again fell ill with similar symptoms. This time he was diagnosed with gastroenteritis and, once more, after a few days, he was back to his normal rude health.

In October 1935, the Bryant family moved to a new cottage at Coombe. It was around this time that Leonard Parsons' attraction for Charlotte began to show signs of waning. Afraid that he was about to leave her, Charlotte tried numerous ways to keep him by her side. First, she hid his clothes. A few days later, she visited a garage where he had left his car for repairs. Posing as Mrs Parsons, she told the garage owner to be careful about working on the car since her husband had no means of paying the bill.

Her efforts were in vain as, in November, Parsons left the Bryant household never to return. Charlotte, however, had no intention of letting him get away and made strenuous effort to track him down. She hired a car and driver to take her to the Huish Camp to see Priscilla Loveridge. Priscilla wasn't there on that day, but Charlotte managed to speak to her mother, Mrs Penfold, telling her that she wanted to open her daughter's eyes to the baby her partner had fathered. Mrs Penfold asked Charlotte if she had a husband, to which Charlotte replied that she had, but that he was seriously ill in a nursing home and she didn't think he would be coming home.

The following day, Charlotte again secured the services of a driver and headed back to Weston-super-Mare, this time taking Parson's baby with her and also her next-door neighbour, Mrs Lucy Ostler, with whom she had become firm friends. This time, she was more fortunate. Priscilla Loveridge was at home and she and her mother were shown the baby, which bore a strong resemblance to its father, Leonard Parsons.

On 10 December, Frederick Bryant was again stricken with a mystery illness. Working in a stone quarry on the farm, he suddenly doubled over with stomach pain. Having been sick on the grass, he was sent home to recover and, according to one of his workmates, appeared to be dragging his feet as he walked.

He was attended by Dr Tracey who, on examination, found him to be suffering from the symptoms of shock, with a temperature that was well below normal. A seemingly unconcerned Charlotte told the doctor that her husband had suffered similar attacks in the past.

On 20 December, an insurance salesman, Edward Tuck, called at the Bryant's cottage hoping to sell Fred a life insurance policy. One look at the weakened, haggard man was sufficient for Tuck to decide not to proceed with the sale. Later that very day, Fred collapsed again and the Bryant's daughter, Lily, was sent to a neighbour for help. The neighbour, Mr Priddle, accompanied her back to the cottage where he found Fred vomiting profusely, groaning and writhing in agony. Byant asked for some water, but was unable to keep it down. When Charlotte put her husband's illness down to overeating, Priddle took matters into his own hands and telephoned for a doctor himself.

Dr McCarthy saw Bryant on 21 December and made up a prescription for medicine, which Charlotte was to collect from Sherborne that afternoon. Charlotte was away from home for three hours, during which time neighbours cared for Fred. He complained of awful pain, which he described as burning him inside like a red-hot poker and was convinced that he was going to die. When Charlotte returned, she unsympathetically remarked to a neighbour that it was a pity that she hadn't got him insured, saying that at least he could have a military funeral.

Fred received his first dose of medicine at six o'clock that evening, but said that it tasted foul. The medicine was promptly discarded and Fred spent an uncomfortable night in bed with his wife. Mrs Ostler also stayed overnight, sleeping on a pull out bed in the same room.

By morning, Fred's condition had worsened considerably. He had vomiting and diarrhoea and was so weak that he was unable to raise himself from the bed. Dr McCarthy was called and arrived at noon when, finding Bryant now gravely ill, he arranged for his admission to the Yeatman Hospital in Sherborne. It was there that thirty-nine-year-old Frederick Bryant died in agony just a few hours later. The doctor was at his bedside and it occurred to him that Bryant's symptoms were exactly those of arsenic poisoning. He refused to issue a death certificate.

A post-mortem examination was conducted the next day. Charlotte Bryant and Mrs Ostler visited the hospital to collect a death certificate, but once again it was refused. There would have to be an inquest, Charlotte was told.

Charlotte was not sure what this procedure involved but Mrs Ostler explained that âthey must have found something in his body which didn't ought to be there.' On their way home, the two women bumped into Edward Tuck, the insurance agent, who gallantly offered to drive them back to Coombe. During the journey, Tuck was struck by Charlotte's conversation. âThey can't say

I

poisoned him', she stated repeatedly, emphasizing the âI'. âI've been a good wife to him and nobody can say I haven't.'

The inquest opened on 24 December but was adjourned over Christmas. When it reopened on 27 December, a second post-mortem examination was ordered and Frederick Bryant's internal organs were sealed in jars and sent to Home Office analyst Dr Roche Lynch for testing.

Meanwhile, Dorset police began an intensive search at the Bryant's cottage. The investigating officers, led by Chief Inspector Alex Bell and Detective Sergeant Tapsell, sent Charlotte and her five children to the public assistance institution at Sturminster Newton, where she was shortly joined by her neighbour Lucy Ostler and her seven children.

With the widow Bryant and her children out of the way, numerous bottles, tins and items of clothing were removed from the cottage for testing. The floors were swept and the dust was collected. The Bryants' cat, dog, chickens and pigeons were put to sleep so that their bodies could be analysed. While police were conducting their search, a puppy from the farm on which the cottage stood died suddenly and unexpectedly. It, too, was subjected to a post-mortem examination but no connection could be found between its death and that of Fred Bryant.

Charlotte and her children were interviewed, as were Lucy Ostler and other neighbours. However, police were initially unable to trace Leonard Parsons in spite of sending cars to search large areas of Dorset, Somerset and Devon.

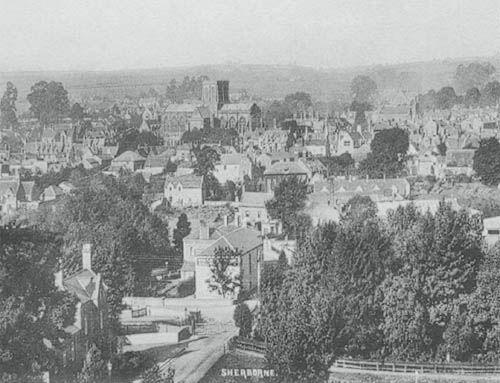

View of Sherborne

.