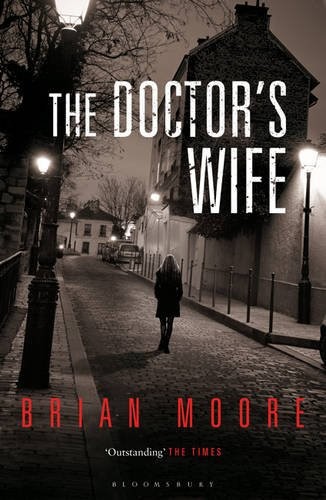

Doctor's Wife

Authors: Brian Moore

The Doctor’s

Wife

Brian Moore

Farrar, Straus and Giroux • New York

Copyright © 1976 by Brian Moore

All rights reserved

First printing, 1976

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Cynthia Krupat

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication

Data

Moore, Brian. / The doctor’s wife. / I.

Title.

PZ4.M81QDOC3 /

[PR6063.06] / 813’.5’4

76-21294

For Jean

The Doctor’s

Wife

Prelude

• The plane from Belfast arrived on time, but when

the passengers disembarked there was a long wait for baggage. “This

plane is full seven days a week,” said a chap who stood beside Dr.

Deane watching the first suitcases jiggle down the conveyor belt.

“It’s the best-paying run in the whole of the British Isles,” the

chap said. Dr. Deane nodded: he was not a great one for

conversation with strangers. He saw his soft canvas bag come down

the ramp looking a bit worn at the edges, and no wonder. It had

been a wedding present from his fellow interns twenty years ago. He

picked up the bag, went outside, and took the bus to Terminal II to

catch the twelve o’clock flight to Paris. It was raining here in

London. It had been very blustery when he left home this morning,

but the weather forecast had predicted clear skies over the

southeastern part of the British Isles. In the airport lounge,

after being ticketed and cleared, he decided to have a small

whiskey. It was early in the day, but he thought of the old Irish

licensing law. A bona fide traveler is entitled to a drink outside

normal hours.

On his way to the bar, Dr. Deane stopped at the

newsstand and, after browsing, bought the

Guardian

and a

copy of

Time

magazine. He then went and stood, a tall

lonely figure, at the long modern bar. “John Jameson you said,

sir?” the barman asked, and found the bottle. When Dr. Deane saw

the amount of liquid poured in the glass, he remembered that he was

in England. “Better make that a double,” he said.

“A double, very good, sir.”

He tasted the whiskey. Over the intercom a voice

announced flights to Stockholm, Prague, and Moscow. He still found

it odd to think that people could walk out of this lounge and get

on planes for places which, to him, were just names in the

newspaper. When he had finished his whiskey, he took two Gelusil

tablets. He had ulcers, a family ailment, had had two bleeds over

the years, and was supposed to be careful. Lately, he had been the

opposite. Of course everyone at home drank more these days. It was

to be expected.

When his flight was called, he was one of the first

to board the bus that took the passengers out to the waiting

aircraft. On the bus, he unbuttoned his fly-front raincoat,

revealing a green tweed suit, a yellow shirt, and a green tie. The

colors made his face seem failed and gray. His wife liked to choose

his clothes for him. She had no taste. He knew this, but did not

argue with her. He was fonder of peace than she.

Ahead, like wound-up toys, a line of planes crawled

toward the takeoff point. Dr. Deane watched a huge American jet

begin its lift-off into the rain-filled sky and wondered if he

himself were taking off in the wrong direction. And then, with a

rush of engines, his own plane was airborne and he was watching the

English countryside below. If you could call it countryside. So

many more houses and roads and people than at home. Fifty million

on this island and less than five million in all of Ireland.

The plane came through rain and cloud to the clear

skies predicted in that morning’s forecast and, after a while, the

stewardesses came around selling cigarettes and drinks. He ordered

a Haig and noted that, duty free, it cost a quarter of what he had

paid for the Jameson in the airport bar. Unbuckling his seat belt,

he lifted the glass, looking at the pale yellow of the Scotch. His

wife was dead against his making this trip, needle in a haystack,

wild-goose chase, all the clichés she had in that head of hers. He

had warned her to tell nobody, but perhaps that was asking more

than she had in her. He looked down, saw that the plane was already

over water, and craned his head back trying to catch a glimpse of

the white cliffs of Dover. The stewardesses were coming up the

aisle again, bringing trays of cold lunch. He thought of the letter

that had turned up in Paris two days ago, a letter from the

American, addressed to Sheila, in care of Peg Conway. His

tachycardia began. It’s just nerves, my heart’s all right. I’m all

right. I’m going over to see Peg and to talk to that priest. To see

what I can find out.

The stewardess leaned in from the aisle holding a

plastic tray on which were a plate of cold meat, a cream puff, and

a green salad. “Are you having luncheon, sir?”

Dr. Deane did not feel hungry but there was his

ulcer to be fed. He accepted the tray.

•

Peg Conway, a small woman, came in again from the

front hall of her flat to stand like a child before Dr. Deane’s

lonely height. Old-fashioned, he had risen from the sofa as she

re-entered the living room. “Please don’t get up,” she reassured

him. “Here it is.”

Dr. Deane turned the letter over in his hands,

noting the American airmail stamps, the address to which it had

been sent:

MME SHEILA

REDDEN

C/O CONWAY

29 QUAI

SAINT-MICHEL

PARIS, 75005

FRANCE

Faire

suivre, s.v.p.—

Urgent.

Please forward

And the address from which it had been sent:

T. LOWRY

PINE LODGE

RUTLAND, VERMONT

05701

U.S.A.

“You’ll see that it was posted in Vermont on the

second. That’s four days after they were supposed to leave

Paris.”

Dr. Deane lowered himself back down on the worn

brown velvet sofa. He tapped the envelope on his knee.

“Why don’t you open it?” Peg said.

He smiled nervously, and looked at the letter again.

“Ah, no, I don’t think I should do that. It wouldn’t be right.”

“It’s an emergency, after all.”

“I know.”

“Look,” Peg said. “She’s supposed to be in America.

Well,

is

she? Look at the date on the envelope. If he

wrote her that letter, it means they’re no longer together.”

“Not necessarily.” Dr. Deane lit a Gauloise from a

crumpled pack. “She might have got cold feet that night, then

joined him later.”

“After the letter was posted?”

“Exactly.” He inhaled and blew smoke through his

nose.

“I thought doctors didn’t smoke nowadays.”

“I backslid.”

“So, what’s your next move?”

“I was thinking,” Dr. Deane said. “It’s just

possible she’s with him now, at that address in Vermont. I might

try ringing her up.”

“You mean, ring up America? That Pine Lodge

place?”

“Yes.”

“You’d rather do that than open the letter?”

“Yes.”

“Well, all right, then,” Peg said. “It’s an idea.

Look, I’ll go and get supper started. That way you won’t be

disturbed if you do reach Sheila. The phone’s over there.”

“I’ll find out the charges on the call, of

course.”

“Don’t worry about that.”

He stood up as she left, then heard her shut the

kitchen door with a loud noise, indicating that he would not be

overheard. A big tabby cat came stalking in from the hall, arching

its back, then leaning against his trouser leg. He looked again at

the address on the envelope, and went to the desk where the phone

was. Through Peg’s French windows he could see the Seine far below,

winding through the city; to his left, the floodlit spire of the

Sainte-Chapelle behind the law courts, and, downriver, the awesome,

sepulchral façade of Notre-Dame. To look out at a view like this,

so different from any view at home, to pick up the telephone and

speak words which would be carried by undersea cable to that huge

continent he had never seen. It was as though he were not living

his own life but acting in some film, a detective hunting for a

missing person or, more likely, a criminal seeking to make amends

to his victim. And now, dialing, and talking to an international

operator, within a minute he heard a number ring, far away, clear

and casual as though he were phoning someone just down the

street.

“Pine Lodge,” an American voice said.

“I have a person-to-person call from Paris, France,”

the operator said. “For a Mrs. Sheila Redden.”

“I’m sorry, we don’t have anyone registered by that

name.”

Dr. Deane cut in. “Do you have a Mr. Tom Lowry

there?”

“Sir, hold on, do you want to make that

person-to-person to Mr. Lowry instead?” his operator asked.

“Yes, please.”

“Thank you. Hello, Vermont? Do you have a Mr. Tom

Lowry there, please?”

“Okay, hold on,” the American voice said. “Tom?

Paris! Take it on two.”

“Hello”—a voice, young, very excited.

“Mr. Lowry, I’m Sheila’s brother and I’m calling

from Peg Conway’s flat in Paris. My name is Owen Deane.”

“Oh.” The voice went cold. “Yes?”

“I’ve been trying to get in touch with Sheila. I

want to talk to her about some money I’m supposed to send her. Is

she there?”

There was a moment’s hesitation. “I’m sorry, I can’t

help you.”

“I’m calling because there’s a letter here from you,

addressed to Sheila. We thought she was with you. Naturally, we’re

worried about her.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Well, look, if you know where she is, would you

please pass a message on to her? Would you tell her to ring me

collect in Paris at the Hôtel Angleterre? I’ll give you the

number.”

“I’m sorry. Goodbye,” the boy’s voice said. The

receiver clicked.

Dr. Deane stood, holding the phone, his heart

starting up with the tachycardia that had affected him ever since

this business had started. He put down the receiver, saw his pale

face in the mirror, and, again, thought of what she had said to him

that day.

Forget me. I’m like the man in the newspaper story,

the ordinary man who goes down to the corner to buy cigarettes and

is never heard from again

. To think it was only four weeks

since she came here to Paris to start a perfectly ordinary summer

holiday. She came to this flat, she stood in this very room. His

eyes searched the mirror as though, behind him, his sister might

reappear. But the mirror room gave him back only his own

reflection, his Judas face.

Part 1

Chapter 1

• Put your things in the spare room, Peg had

written, and make yourself at home, because I won’t be back till

six. Sheila Redden let down her heavy suitcase and felt under the

carpet runner on the top step of the stairs where Peg’s letter said

it would be. She pulled the key out, put it in the lock, and the

door opened inward with a groan of its hinges. As she bent again to

pick up the suitcase, a big tabby cat bounded past her, skipping

into the flat. Would that be Peg’s cat? Mrs. Redden went inside,

calling “Puss, Puss,” although Puss wouldn’t mean much to a French

cat, she supposed. Weren’t French cats called Minou? She went into

the front hall, still calling “Puss, Puss,” damned cat, but then

she saw it, very much at home, lapping water from a cat dish in the

kitchen. So that was all right. She took off her coat.

It was quiet here: this far up, the street noises

blurred to a distant monotone. In the living room, thinking of the

great view there must be, she unlocked the middle set of French

windows and stepped out onto the narrow balcony. Below her, the

Seine wound among streets filled with history no Irish city ever

knew and, as she looked down, from the shadowed underside of the

Pont Saint-Michel a sightseeing boat slid into sunlight, tourists

massed on its broad deck staring up in her direction. If they saw

her, she would seem to them to be some rich French woman living

here in luxury, right opposite the Ile Saint-Louis. The sightseeing

boat slid sideways, as though it had lost its rudder, but then,

righting itself, went off toward Notre-Dame in a churn of dirty

brown water. Mrs. Redden leaned out over the iron railing to look

down six floors to the street, where white-aproned waiters, tiny as

the bridegroom figurines on a wedding cake, hurried in and out

among sidewalk tables. Into her mind came the view from her living

room at home. The garden: brick covered with English ivy, Belfast’s

mountain, Cave Hill, looming over the top of the garden wall, its

promontories like the profile of a sleeping giant, face upward to

the gray skies. Right opposite her house was the highest point of

the mountain, the peak called Napoleon’s Nose. She thought of that

now, staring out at Napoleon’s own city. L’Empereur on his white

charger Marengo, riding into the Place des Invalides, triumphant

after Austerlitz; clatter of hoofbeats on cobblestones, silken

pennants, braided gold lanyards, fur shakos, the Old Guard.

Napoleon’s Nose. And this. She stepped inside again, closing the

big windows, going to the front hall to get her suitcase. But

then—it put the heart across her—heard someone moving about inside

the flat.