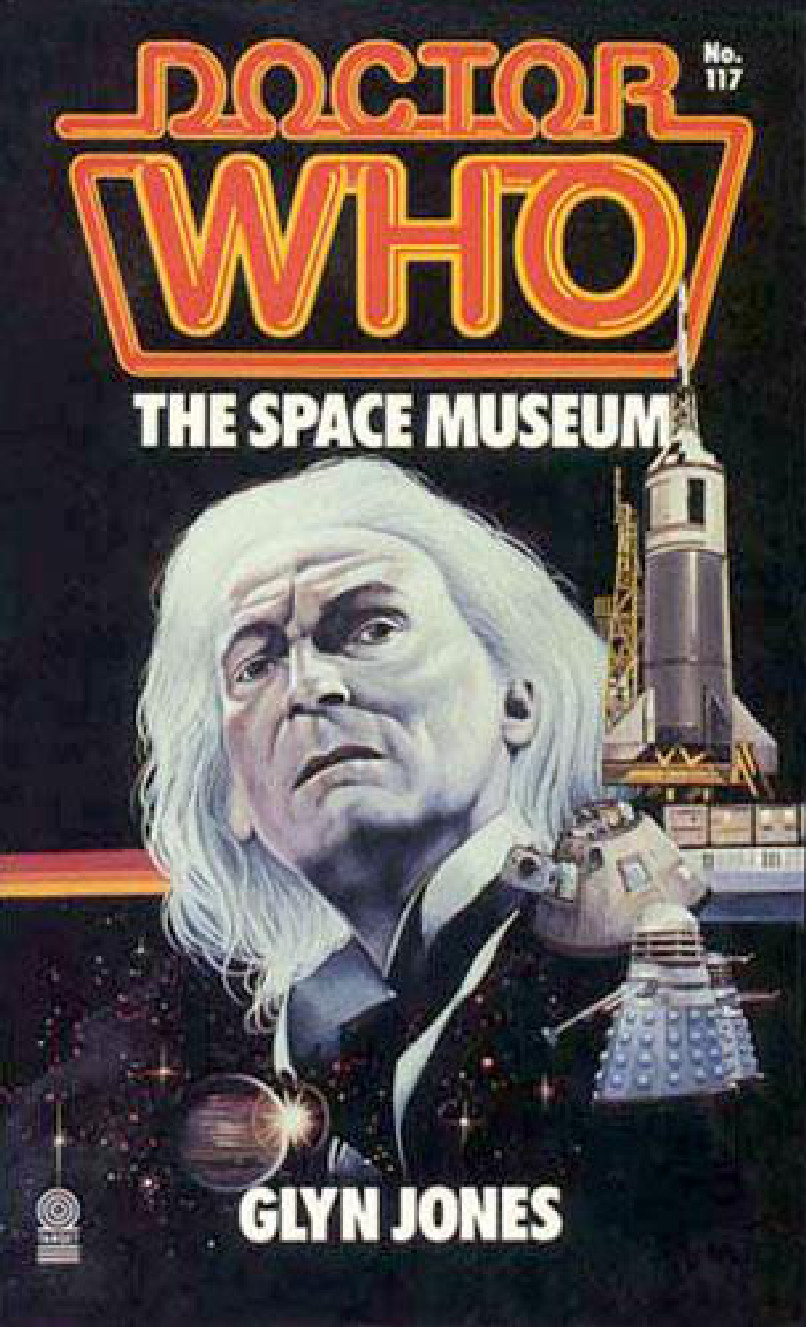

Doctor Who: The Space Museum

THE SPACE MUSEUM

GLYN JONES

Based on the BBC television series by Glyn Jones by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation

Number 117 in the

Doctor Who Library

A TARGET BOOK

published by

the Paperback Division of W. H. ALLEN & CO. PLC

Three pairs of eyes gazed at the scanner screen, eyes like those of a sad and lonely person in a strange town desperately seeking the smile of a friendly face. The fourth pair of eyes gave no hint of emotion. The Doctor was totally absorbed, totally fascinated.

Vicki sighed, a sigh so audible that Ian could not resist a sidelong glance at his young companion. He turned back to the screen and, knowing exactly how she felt, almost mechanically placed a comforting arm across her shoulders. She didn’t seem to notice. Barbara sighed, perhaps not quite so audibly but, with gentlemanly impartiality, Ian’s other arm reached out to comfort her.

All he could see on the screen was sand, sand, sand, and more sand. Why couldn’t the TARDIS, just once, materialise in a pleasant, leafy, tree-lined street in Hampstead, or on Wimbledon Common? How about a pretty Yorkshire dale, or a Welsh mountain top with nothing around more menacing than a flock of silly sheep? Or, if it had to be sand, why not a sun-drenched Californian beach? Or maybe even the South of France? Yes, there was a pleasant thought: cafes and cordon bleu restaurants, palm-shaded promenades and contented humans basking on that sand, soaking up the sun’s rays through their sunscreen, swimming and playing in a beautiful blue and silver sea; smiling, laughing, happy people, sipping cool drinks, tasting delicious ices. At that moment Ian could almost taste tutti-frutti.

And why couldn’t the TARDIS materialise in the good old twentieth century, in some peaceful corner of the world where they could just relax and not be caught up in the stupidity of human wars or some other folly? Ian sighed deeply and three pairs of eyes turned to look at him. He did not return their gaze but he felt himself blush.

‘Where are we?’ he asked, as though they were travelling from London to Manchester and he just happened to have dozed off for a few minutes. The eyes turned back to the screen and now, for the first time, something other than sand appeared as the scanner moved on.

‘A rocket!’ Ian squeaked. ‘In the middle of miles and miles of nothing but sand?’

It was the Doctor’s turn to sigh but, before he could say anything, a second rocket appeared, then another, and another; then a spaceship, and a second spaceship, and more spaceships, so many ships of such diverse shapes, periods, and design that now four pairs of eyes were rivetted to the screen.

There was no sign of life, only the ships, motionless in a sea of sand. And then, beyond them, a building came into view. The scanner moved in for a closer inspection. The building was large, very large, in shape something like a ziggurat. The surface was made up of geometric panels, triangles forming pyramids, and covered with what seemed to be a dullish metal which, although the sky was bright, gave off no reflection.

‘It’s the casino,’ Ian thought, his mind still on sunlit beaches and gentle pleasures, ‘like the casino at Monte Carlo, or Nice. We’ll find two-headed monsters playing three-dimensional roulette.’ He chuckled to himself and then stopped, in case someone decided to investigate his sense of humour. He needn’t have worried. Everyone was too engrossed in studying the building in question. He was intrigued though by the non-reflective panels. ‘Do you suppose this planet has a sun?’ he queried.

The Doctor shrugged. ‘Presumably,’ he muttered,’otherwise where would the light be coming from?’

‘I only asked.’ Ian was a trifle peeved at the Doctor’s brusque reply. He was anxious now to be up and about doing something, and the Doctor, as far as he was concerned, was being his usual cautious self. Ian sighed again.

‘What is the matter with you, my boy?’ the Doctor snapped. ‘If you carry on like that you’ll sigh your life away.’

‘There doesn’t seem to be any sign of life,’ Ian answered, ‘Why don’t we go and take a closer look? Hmm?’

‘Oh, so you want to go and take a closer look, do you? Well go ahead, no-one’s stopping you.’

‘I’m not going on my own!’

‘Then you’ll just have to be patient and wait for us, won’t you?’ And the Doctor turned his attention back to the screen. Ian glowered at the top of his companion’s head. ‘And it’s no good looking like that,’ the Doctor added, ‘if the wind changes direction you’ll stay that way.’ And he chuckled to himself.

Ian folded his arms, deciding not to say another word, and it was Vicki who eventually broke the silence.

‘Have you noticed something?’ she asked no-one in particular and everyone in general.

‘What is that, my child?’ The Doctor peered benignly at her, smiling encouragement. Ian snorted, but not too loud, just enough to show he didn’t approve of favouritism.

‘We’ve got our clothes on,’ Vicki said.

‘Well, I should hope so, I should hope so indeed!’ The Doctor sounded quite shocked.

‘No,’ Vicki persisted, ‘I mean, our ordinary, everyday clothes.’ She looked from one to the other. No-one seemed to understand what she was getting at. ‘Barbara, what was the last thing we were wearing?’ she asked.

‘We were at the Crusades,’ Ian said. ‘Are we never going to get away from deserts?’

‘Exactly,’ Vicki replied. ‘So why aren’t we still in our crusading clothes?’

‘Because we’re not crusading anymore,’ Ian laughed.

‘I don’t think it’s funny,’ Vicki said, ‘I’m being perfectly serious. How did we get from our crusading clothes into these, and where are those clothes now?’

‘Probably hanging up where they should be,’ the Doctor suggested, ‘And if it concerns you that much, I suggest you go and take a look.’

‘Very well, I will,’ Vicki pouted and turned to go. ‘Oh, and on your way back,’ the Doctor continued, ‘you might fetch me a glass of water. I’m quite parched.’ ‘It’s all these deserts,’ Ian said.

‘I don’t know,’ the Doctor muttered, ‘all this fussing just because our clothes change. It’s time and relativity, my boy, time and relativity, that’s all. That’s where the answer lies.’

‘I dare say,’ Ian replied, ‘but we’d be much happier if you explained it.’

‘Yes, well... er... yes...’ The Doctor didn’t quite know how time and relativity should affect their apparel or, to be more exact, their change of apparel, but felt somehow he should. However, he wasn’t going to admit it so turned back to the control panel and flicked a few switches at random, hoping something interesting would come up on the screen to divert attention from his lack of perception. But it was Vicki’s voice that created the diversion as she called from the sleeping cabin. ‘Our crusading clothes are here, Doctor!’

‘Hmm? Oh, good, good.’ Feeling somehow vindicated he looked up at Ian and Barbara and smiled. ‘You see?’ The two exchanged a wry look.

Feeling a little like Alice in Wonderland, Vicki stood staring at the neatly hung clothes. It was all most peculiar. What was the last thing she remembered? ‘I blacked out,’ she murmured. ‘How could I change my clothes if I blacked out? And the others didn’t seem to know anything so presumably they must have blacked out too.’

Shaking her head, she moved away, though the puzzle stayed with her. She filled a glass with water and turned to go. The hanging clothes caught her eye and, still distracted, she let the glass slip from her fingers.

It seemed an eternity before it hit the floor and shattered. She watched it happen almost as if it were in slow motion. Then, before she could do anything, a reversal took place. The fragments of glass came together again and seemingly leapt into her open hand, an intact and full glass of water. Vicki was too amazed to do anything other than stand and gape.

And she was not the only one. In the console three pairs of eyes were staring at the space-time clock. It was Barbara who had seen it first and her gasp of astonishment had immediately caught the attention of the others.

The clock read ‘AD 0000.’

‘What on earth does it mean?’ Ian whispered when he had more or less rediscovered his voice. ‘I mean, if we were on Earth, what on earth would it mean?’

‘Perhaps it’s broken down,’ Barbara ventured hopefully.

‘I certainly hope so,’ was the rejoinder. ‘It’s like being suspended in time, in limbo, and that doesn’t appeal to me one little bit.’

Vicki, carefully nursing her glass of water, entered the console room to be brought up short by the expression of Ian’s sentiments and she too joined in the contemplation of the clock.

‘Perhaps it has something to do with our blacking-out,’ she said finally.

Ian turned to the Doctor. ‘What do you make of it?’ he asked.

The Doctor shrugged, meaning he didn’t make much of it at all. ‘Well...’ He tapped the side of his nose and pursed his lips, then went on ‘... it could be any one of a dozen things.’

Barbara and Ian exchanged glances.

‘There’s no such year of course,’ the Doctor went on. ‘You’ve probably worked that out for yourselves already. I’ve only ever had trouble with that clock once before.’ He wagged an admonishing finger at the offending instrument. ‘That was when Augustus Caesar created his own calendar and left a day out of the one I’d been working on. Very inconsiderate. Amateurs should not tamper with things they know nothing about.’

‘I wouldn’t have thought just one day would make all that much difference,’ Barbara said.

‘One day per year over several million years is quite significant, Barbara.’

‘Yes, of course,’ Barbara agreed.

Ian resisted the temptation to say that several million years hadn’t passed since the time of Augustus and instead, somewhat impatiently, he asked, ‘Yes, but what has happened this time?’

But the Doctor had given himself time to think. He put out a hand in a most delicate gesture and inclined his head slightly. It was something he had once seen Lao-Tzu do and it had impressed him mightily. It certainly had had the desired effect on the lapsed disciple at the time.

‘Patience,’ he gently chided, ‘I’m just coming to that. After that impertinent piece of Roman interference I decided I couldn’t have the clock going wrong again. It took far too long to repair. So I decided on an added refinement. If something is about to go wrong the dials set themselves in the position you see now and the clock isolates itself from the circuit. Saves a tremendous amount of trouble.’ He was glad he had remembered this and smiled, well pleased with himself.

‘Then something has gone wrong,’ Barbara said simply. ‘Yes, I suppose it has,’ the Doctor replied, equally as simply and feeling somewhat deflated.

‘Well what can it he?’ she persisted.

‘I don’t know.’ For a moment his admission of fallibility deflated him even further but the sudden look of panic on the faces of his companions quickly brought him round. ‘Obviously,’ he said in his most authoritative manner, ‘the trouble is a direct result of time friction..’

‘What is that?’ Ian asked, unable to hide the incredulity in his voice.

‘A sort of space static electricity, I suppose, would be the best description,’ was the answer.

‘I know!’ Vicki burst in. ‘Like people have when they can’t wear a watch. You know, they put the watch on their arm and it stops but, when they take it off, it starts again. And then when they...’

‘All right, Vicki,’ Ian cut in, ‘we’ve got the picture.’ He turned back to the Doctor. ‘You mean it would set up some sort of interference with the clock mechanism?’

‘Well, something has!’ the Doctor snapped.

Ian nodded his head slowly. ‘So the clock reverted to the safety device.’

‘Well done,’ the Doctor congratulated him, not without a hint of sarcasm.

‘You don’t seem at all worried,’ was the response. The Doctor’s eyes narrowed. Was Ian on the attack or merely stating what he thought was obvious? He decided to parry the question. ‘Why should I be?’ he shrugged.

‘All right...’

Wait for it, the Doctor thought, here comes the thrust... What year are we in?’

The Doctor parried again. ‘A good question,’ he said.

‘Deserves a good answer. After all, we’ve got billions to choose from. Shall we take a guess and see who is the closest?’

‘Ian!’ It was Barbara deciding to cut short the discussion. She wasn’t prepared to referee a fight and was also aware that Vicki was getting frightened.

‘There is no need to guess,’ the Doctor said. ‘The clock has a built-in memory. It will adjust itself as soon as we move off again. Time friction has a convenient habit of being localised.’

‘Do you think it was this time friction that made us go to sleep?’ Vicki asked.

‘Oh, no doubt about it.’ The Doctor felt he was on firmer ground again. ‘Just as the clock protected itself by becoming neutralised, so we have been protected by falling asleep. At least that is the best theory I can advance at the moment.’

‘All right,’ Ian said, ‘I accept the fact that we don’t know when we are, but couldn’t we at least try to find out where we are?’

‘Certainly... Of course... Immediately.’ The Doctor returned to his seat and his dials.