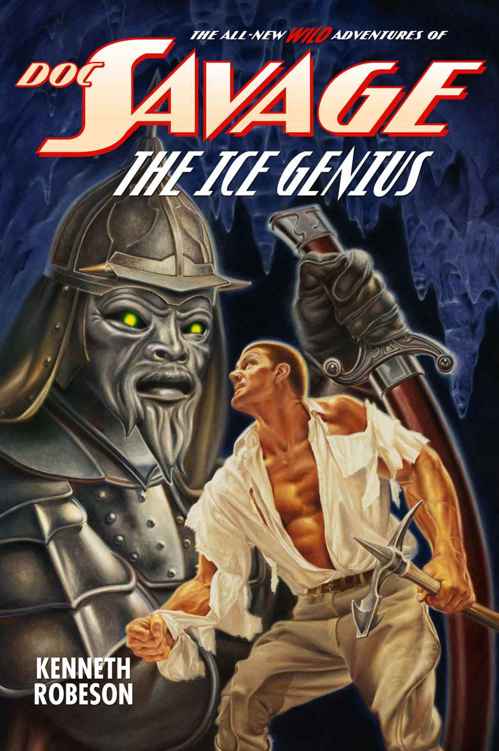

Doc Savage: The Ice Genius (The Wild Adventures of Doc Savage Book 12)

Read Doc Savage: The Ice Genius (The Wild Adventures of Doc Savage Book 12) Online

Authors: Kenneth Robeson,Will Murray,Lester Dent

Tags: #Action and Adventure

The Ice Genius

A Doc Savage Adventure

by Will Murray & Lester Dent writing as Kenneth Robeson

cover by Joe DeVito

Altus Press • 2014

The Ice Genius copyright © 2014 by Will Murray and the Heirs of Norma Dent.

Doc Savage copyright © 2014 Advance Magazine Publishers Inc./Condé Nast. “Doc Savage” is a registered trademark of Advance Magazine Publishers Inc., d/b/a/ Condé Nast. Used with permission.

Front cover image copyright © 2014 Joe DeVito. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Designed by Matthew Moring/

Altus Press

Like us on Facebook:

The Wild Adventures of Doc Savage

Special Thanks to James Bama, Jerry Birenz, Condé Nast, Jeff Deischer, Norma Dent, Dafydd Neal Dyar, Bob Gasparini, Dave McDonnell, Lohr McKinstry, Matthew Moring, Brian Pruitt, Ray Riethmeier, Howard Wright, The State Historical Society of Missouri, and last but not least, the Heirs of Norma Dent—James Valbracht, John Valbracht, Wayne Valbracht, Shirley Dungan and Doris Leimkuehler.

Dedication

For Marc Jaffe—

The visionary Bantam Books editor who had the foresight to revive the Man of Bronze fifty years ago in 1964.

Chapter I

COLD CAVERN

THE MOST MOMENTOUS discoveries are sometimes made by accident, so history tells us.

The navigator Christopher Columbus, considered a great man today, set out to discover a short cut to the East Indies, and stumbled upon the New World, hitherto unknown.

It was an accident. Ignorance of the world’s true geography resulted in the great discovery. That Columbus died in abject poverty matters not a whit. The world changed forever because of him.

The scientist Sir Isaac Newton, resting beneath a fruit tree, discovered the mysterious force called gravity because a common apple chanced to collide with his skull.

The European continent, it is said, was on the verge of being conquered by the Mongol warlord, Sabatoi, when word of the death of his chieftain, the fearsome Genghis Khan, reached his ears. Sabatoi Khan promptly turned his horde around and Europe was spared horrors undreamed.

A few centuries later, Europe was scourged by plague—the direct result, historians claim, of a lack of hungry cats to keep the flea-bearing rodent population in check. Superstitious belief that cats were in league with the Devil had brought about their unfortunate downfall. Without cats, the rats thrived. Plague-bearing fleas enjoyed free reign. And for the lack of tabby cats, humanity suffered greatly.

More recently, an Austrian nobleman’s touring car happened to take a wrong turn. This detour brought the nobleman into the sights of his assassin. And his death became the spark that plunged the modern world into the bloody fuss called the World War, in which ten millions died.

Accidents. Mistakes. Happenstance. By such freakish gyrations do the wheels of history sometimes turn.

So it was with William Harper Littlejohn, the eminent archeologist and geologist. The history book publishers had already set aside a barrel of ink with which to enter the prodigious accomplishments of Professor Littlejohn in future tomes, as well as a roll of the finest paper the size of a box car to print the laudatory words upon, when William Harper Littlejohn made the most amazing discovery of his remarkable career.

It was, as it turned out, the most terrible one, as well. Great fame would attach itself to the renowned archeologist because of it, and great sorrow, too. By the time the world learned of it all, William Harper Littlejohn had reached the dark place in his soul wherein he would have gladly swapped his discovery for the peace of mind he had enjoyed before he found the strange cave on the arid steppes of Mongolia.

Ironically, William Harper Littlejohn had come to the rough land in search of bones. Human bones to be exact. Pre-historic human bones, to be absolutely clear about it.

The scientific world was in a frame of mind that caused them to think that early man, primitive man, had first come into this sorry world in Mongolia. The theory was not exactly new, but with the Japanese gobbling up parts of Asia at an alarming rate, the world’s archeologists were concerned that any discovery of proof that man came forth in the Gobi wastes would be lost forever—or at least delayed many generations—should Mongolia be consumed by spreading war before any prehistoric bones were found.

So a great many archeologists representing the finest universities all over the world piled into chartered aircraft and picked spots for their digging. William Harper Littlejohn just happened to be one of the many.

Still, it was an accident, the horrible thing that happened.

For a land reputed to be the birthplace of Adam and Eve—if the paleontologists were correct in their surmises—Mongolia was no Garden of Eden.

The area outside the few cities the great sprawling country boasted consisted mainly of snow-capped red-brown mountains and flat, endless steppes. Cold, bitter, barren land, barely able to support the wandering nomads who moved with the seasons, seeking the tough scrub grass that sustained their sheep and shaggy ponies.

And there were bandits.

Most of the bandits had come up from the Manchurian border, fleeing Japanese occupation. They were cruel devils, accustomed to bloodshed. Their trade was pillage, but bandits on ponies were no match for Japanese warplanes and armor-plated tanks. Besides, there was no money in fighting Japanese. Only sudden death.

This particular band of brigands had ranged up into the south of Mongolia, where they lived off the land by pillaging the tiny camps of Mongol sheep herders. By reputation, Mongols are fierce fighters, and after four or five months of this activity, each member of the bandit band could boast of owning two fine ponies—the original owners of the riderless ponies having succumbed to Mongol blunderbusses.

So it was decided one howling night around a feeble campfire that in the future more worthy victims would be selected. This decision was arrived at after three days’ argument and many flagons of sour

kumis

—fermented mare’s milk—had been quaffed.

When their minds cleared, the bandit group shoved assorted knives and pistols into the sashes of their voluminous robe-like coats, mounted their ponies and, waving rifles in the air, set out in search of more suitable victims. Ones that did not shoot back, was the unspoken assumption.

They rode like wild Indians. The war cries they offered the impossibly blue sky would have done credit to Cochise.

When they appeared on a ridge overlooking the archeological site where William Harper Littlejohn was doing his excavating, silhouetted against the setting sun, they looked remarkably like Comanches—minus the eagle feathers.

“An equestrian calamity impends,” muttered William Harper Littlejohn, who had been speaking the Mongolian tongue for so many weeks now he had all but forgotten his English.

Despite having held the Natural Science chair in a prominent American university in his past, William Harper Littlejohn was currently affiliated with no particular seat of learning. Thus, he had no white helpers. Only Mongols willing to do the hard, dusty work for which he paid them in good American greenbacks.

Hearing William Harper Littlejohn’s tone of voice, the Mongol helpers looked in the direction he was staring.

And their chins began trembling.

“Bandits!” a man hissed.

Then, as if the hissed word had carried all the way up the ridge, the bandits let out a whoop and their ponies plunged down, kicking up dirt and grass.

They were a blood-curdling sight.

NOW, digging for fossil bone is not unlike drilling for oil. Locations do not advertise themselves. To the untrained eye, one great patch of inhospitable land looks much like another.

Johnny Littlejohn—they called him Johnny, never William or Bill—had selected this particular patch of ground for two reasons, both having to do with the great ridge which the setting sun threw into shadow. First, the ridge kept the prevailing winds from burying the stretch with bone-covering soil. Second, it also cut the bitter winds so prevalent this time of year.

Johnny dropped a short-handled shovel and sifting tray that might have been used to pan for gold at one time, and unfolded his wonderfully bony length in the direction of a duffel bag with alacrity.

The duffel bag was something he kept at hand at all times. The gangling geologist was not, like some college products, ignorant of the perils of Mongolia.

As his helpers dived for the protection of the pit they had been excavating, Johnny fished out a remarkable weapon from the bag. It resembled an ordinary automatic of foreign manufacture. But it was very large for an automatic. There was a drum mounted before the trigger guard and Johnny yanked this off. He fumbled in the bag for another as the bandits continued negotiating their difficult way down the ridge.

The spectacle was not unlike a semi-organized avalanche.

“I’ll be superamalgamated!” declared Johnny in his native tongue, which was a brand of English not ordinarily encountered during common conversation. He had found the drum he was looking for. It had a dab of red paint on it for identification purposes.

The drum was hastily clipped into place, the safety latched off, and the bony archaeologist lifted the weapon. He was, for a moment, a ludicrous sight. Johnny Littlejohn was an elongated articulation of bones and skin—with only the skin keeping him from looking like something dug out of the pit after burying. A white pith helmet sat on his long skull like an inverted bowl precariously balanced on the shaggy end of a mop. Tied to the lapel of his jacket was a monocle too thick to be used as such.

No man with a pistol can hope to overcome a wall of hard-riding bandits—even if the pistol is equipped with an ammunition drum packed with bullets.

Then, a long linkage of skin-wrapped bone that was Johnny’s trigger finger pulled back the firing lever. The weapon’s performance was remarkable. It hooted. An ear-splitting bawl of sound accompanied the furious shuttling of the mechanism, and bullets poured out of the smoking muzzle at a frightful rate. Quantities of brass cartridges dribbled from the breech.

The sound, although loud, was probably lost upon the scrambling bandits, who were preoccupied with making frightful noises of their own.

The commotion that directly followed the striking of the bullets in a line several hundred feet above and behind the line of bandits was impossible to ignore, however.

First, there came a procession of noticeable explosions, spaced fractional seconds apart. The top of the ridge came apart, seemed to fly in all directions at once, and suddenly—gravity exerting its inexorable pull—plunged downward, returning to its former place.

The weight of the returning earth was too much for the broken ridge top. A rumbling landslide commenced.

That was the sound that really got the attention of the bandits. They had already begun throwing open-mouthed glances over their shoulders—neglecting to pilot their mounts would have been dangerous under the circumstances—and these glances rapidly changed character. Surprise followed shock, and shock came hard on the heels of utter terror.