Dixie Betrayed (52 page)

Authors: David J. Eicher

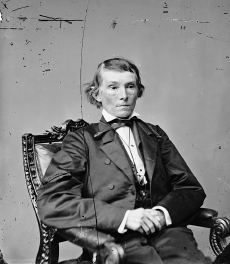

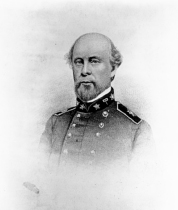

Gruff, audacious Louis T. Wigfall started the war as a Jefferson Davis confidant and transformed into the president’s most vocal critic in the Senate.

Library of Congress

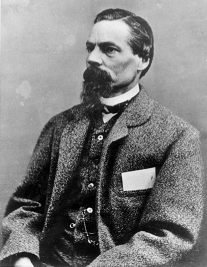

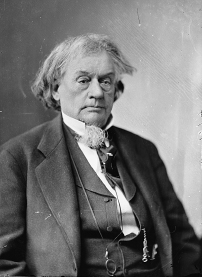

The Confederacy’s vice president, Alexander H. Stephens, was a sickly, frail man who never weighed more than ninety pounds and, according to one newspaper-man, “looked like a freak.” Although charged with presiding over the Confederate Senate, Stephens spent most of the war at home in Georgia, bedridden.

Library of Congress

Dedicated on Washington’s birthday in 1858, the monumental equestrian statue of George Washington gracing Capitol Hill served as a rallying point for Confederates during the war. Others claimed the statue issued a warning, as the general pointed his arm toward the state penitentiary.

Library of Congress

Three long blocks northeast of Capitol Square, at Twelfth and Clay streets, stands the John Brockenbrough House, now known as the White House of the Confederacy. This lovely mansion, built in 1818 and lived in by several occupants before the war — including would-be Confederate Secretary of War James A. Seddon — was purchased in 1861 by the city of Richmond as a residence for the Jefferson Davis family.

Library of Congress

As chairman of the Military Affairs Committee, South Carolina Congressman William Porcher Miles was the most powerful man in the House of Representatives. He disagreed with Davis over a variety of issues, including the need for a Supreme Court and the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus.

The Museum of the Confederacy

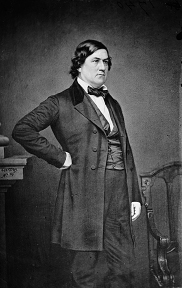

A Virginian who thought like President Davis on most issues, Robert M. T. Hunter was a slow, methodical planner who became Confederate secretary of state and later a senator in Richmond. He staunchly supported state rights and disagreed violently with Davis over the matter of freeing and arming slaves.

Library of Congress

Henry Stuart Foote was one of the most explosive characters in the Civil War South. In 1847 he fought with and nearly dueled Jefferson Davis at a Washington tavern. In Richmond as a Confederate congressman, he claimed to be a “voice of the people” as he constantly attacked the administration. His troublemaking career in the House came to an end when he sneaked away from Richmond on a self-appointed peace mission behind the Yankee lines.

Library of Congress

South Carolina’s celebrated “father of secession,” Robert Barnwell Rhett was the consummate Southern “fire-eater.” A former U. S. senator and owner of the influential

Charleston Mercury,

Rhett was spurned in Montgomery in trying to seize leadership of the Confederacy. He attacked Davis with a passion before leaving Richmond to criticize the administration in angry editorials in the

Mercury

, terming Davis “criminally incompetent.”

Library of Congress

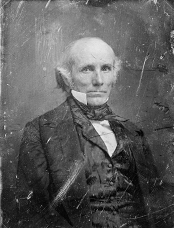

A large man who lived large, Robert A. Toombs was a Georgia politician who was considered too radical for the Confederate presidency. His hard drinking in Montgomery during the genesis of the Confederacy sealed his fate: Davis named him secretary of state for a nation that had no foreign relations. He tired of this and turned to a generalship in the field before returning to Georgia and creating a full-time job of criticizing Davis and his administration.

Library of Congress

This panoramic view of central Richmond includes part of the “burnt district,” the territory of the evacuation fire, and was made by Alexander Gardner on April 6, 1865. The Capitol is visible on the horizon; the Spotswood Hotel stands in front of it. This view was made from Gamble’s Hill.

Cook Collection, Valentine Museum

The Stars and Stripes again flies from the staff atop the Capitol in this Richmond image taken across the James River in April 1865. The burnt district lies between the Capitol and the river; the Customs House, where Jefferson Davis had his office, stands right of the Capitol.

Library of Congress