Disappearances (36 page)

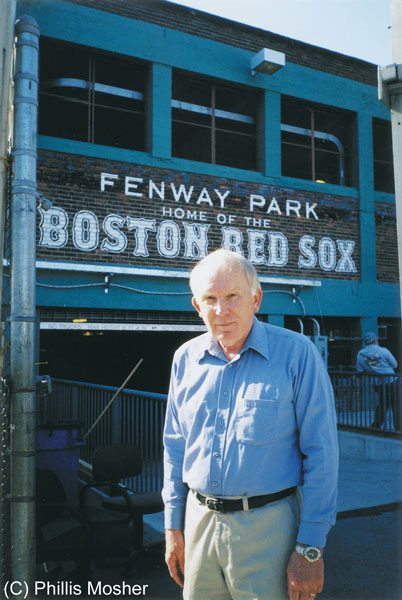

Authors: Howard Frank Mosher

Anything would be better than letting Carcajou drive us deeper into that place of deaths and disappearances. I veered to my left, running with my back to the North Star in an attempt to strike the tote road. Branches dumped snow down my neck and lashed my face. I didn't care. I bulled through a dense stand of cedars, holding my father to one side to protect him from the whipping branches.

“Put me down,” he said. “Put me down. He don't want you.”

As we came out into the raspberry clearing near where I would lose Henry's tracks eighteen years later my father passed out again. His head flopped loosely on my shoulder. In the starlight his long fox's face looked old. Cradling him against me like a baby, the scent of tobacco and woodsmoke strong in my flaring nostrils, I ran.

I knew that the tote road was some distance south of the far edge of the raspberry clearing. In order to reach the road I would first have to circumvent that immense thicket, through which Carcajou now came crashing, shouting in a strange harsh language. I ran between the thicket and the woods with my heart pounding in my ears.

My father said something I didn't catch. I didn't see how Carcajou could move two feet through those raspberry thorns. He was still shouting guttural deep phrases. “Indian,” my father said.

In a different voice Carcajou yelled the words “heathens,” “abomination,” “hell-fire.” “Sinners,” he roared, “you are in the hands of an angry god.”

Indian words. Then that terrifying illusion of many voices shouting simultaneously: a fusillade of Indian, English, French.

“Put me down, Wild Bill.”

I ran faster.

“Close ranks,” Carcajou shouted. “Don't let them rebs break through.”

We seemed to be outdistancing him. I had my second wind and with it the confidence that I could reach the tote road before he did. Once I was on the road nothing was going to overtake me.

Just as I started into the woods between the raspberries and the road I stumbled to my knees. I held onto my father but my foot was caught in a brush pile under the snow. I struggled to pull it out. Carcajou was bearing down on us and baying like a pack of werewolves.

My father didn't realize what had happened. He thought I couldn't carry him any further, that I was floundering under his weight. “For Christ's sake put me down,” he shouted.

Close behind us I could see Carcajou thrashing through the briers. I set my father on the snow and began hacking at the brush around my foot with the hatchet.

“LaChance,” Carcajou bellowed, “you are a dead man.”

As my foot came loose he burst out of the thicket only a few yards away. His clothes had been torn completely off by the thorns. He was the most horrifying sight I have ever seen. I froze in terror. Then I remembered the hatchet.

Carcajou began to scream as I brought back my arm. It was a long bloodthirsty scream of anger, the scream before the kill, indistinguishable from the roar of agony when the hatchet struck his head. I saw a chunk of his head fly out and land in the snow. He fell back into the thicket, where he continued to thrash after the screaming stopped.

I knelt by my father and put my arm around his shoulders. It was very still again. The thrashing in the brush had subsided. Most of the stars had disappeared. It was beginning to get light.

“You got him,” my father said. “This time you really got him, Wild Bill.”

I slid my hand under his knees to pick him up. Then I drew it back out again. It was warm and wet. A dark stain was spreading out over the snow under his right leg.

I took off my jacket and began wrapping it around my father's leg. “You got him all right,” he said.

He reached inside his jacket pocket and pulled out the last whiskey bottle. He looked at the bottle in the thin early light, and then he tossed it into the raspberry bushes.

I picked him up and headed into the trees. By the time I hit the tote road the jacket wrapped around his leg was wet against my arm and chest. My father was unconscious with his head on my shoulder. I took a deep breath and began running down the trace toward the beaver dam. I tried to avoid the single set of large tracks heading my way, as I later saw children trying not to step on sidewalk cracks in the Common.

I stopped to breathe under the cedar tree where years later I would find Henry. The river was open on both sides of the beaver dam. Upriver over the dark water and white trees the dawn sky was as red as the vivid drops of blood behind me in the tote road. Once my father and Uncle Henry and I had tracked a deer that bled in the snow for miles. A strong animal or a strong man could lose a lot of blood before giving up. Maybe I could still get up the hill to the farm in time.

As I stepped onto the dam and started across, my father stirred. He opened his eyes and looked at the red sky. “Ain't that a wonderful sight, Wild Bill?” he said in his strong, slightly rasping voice.

Laughter burst out from behind us. I whirled around and looked up at Carcajou, standing under the cedar tree and laughing. Large patches of the thick white pelt that covered his body were matted dark with blood. Part of the splintered end of the pike pole still protruded out of his left shoulder. The entire right side of his face was encrusted with blood. There were three holes in his upper chest from the bullets my father had fired into him through the windshield of the Buick. His nose was mashed flat against his face. I could see his skull shining through the missing part of the upper left side of his head. In his left hand he held the hatchet awkwardly. In the other was the whiskey bottle. Without taking his eye off us he poured the last of the whiskey down his throat, then dropped the bottle in the snow at his feet and transferred the hatchet to his good hand.

“

Bonjour, petit LaChance,

” he said pleasantly.

“Set me down, Bill.”

I was about halfway across the dam, standing in snow up to my waist. My father's leg was bleeding steadily onto the snow. Again I thought of the bleeding deer we had followed. I was transfixed by the dripping blood, the hush of the water seeping out around the edges of the dam, the horror of Carcajou, watching us with his amused keen blue eye.

I tensed my muscles to make one last run for it. Carcajou anticipated what I intended to do. He took a step and raised the hatchet.

“William!”

Carcajou lifted his head. The voice had come from the far side of the dam. I half turned, holding tightly to my father. Standing on snowshoes on a knoll just above the dam, holding René Bonhomme's musket leveled straight across my head at Carcajou, was Aunt Cordelia.

“You ain't changed much,” Carcajou said past me to Cordelia.

“No one ever does,” she said, her voice harsh and steady. “Put down that tomahawk.”

Carcajou began to laugh. He laughed like a loon, bayed like a wolf, roared and crowed and bellowed like a hundred demons. Cordelia held the musket steady. I noticed that the side hammer was cocked back.

Suddenly Carcajou was quiet. Very slowly, he brought the hatchet up behind his great ruined head. “William,” Cordelia said sharply. “William Goodman.”

Carcajou drew back his arm.

The musket snapped, not loud, and Cordelia was standing in a haze of smoke. Carcajou fell off the bank into the river. His long hair snagged on the dam, and his heavy white body began to twist from side to side in the slow tug of the current. Then before my eyes he vanished.

“William,” Cordelia said, her voice harsh on the cold morning air. “We will go home now.”

My father's weight seemed to have doubled. I didn't know how I could carry him up the hill. My arms ached as though I were holding generations of my ancestors, but when I looked down I realized that they were empty.

“Come,” Cordelia said.

The sun was rising, glinting off Rent's musket, shining on the snow, illuminating the swamp, Kingdom County, Vermont and Quebec. Downriver a loon hooted. Its long wild call floated over the water and trees and snow as I stood with empty arms on the edge of my youth in a place wheeling sunward, full of terror, full of wonder.

Â

H

OWARD

F

RANK

M

OSHER

is the author of ten books, including

Waiting for Teddy Williams, The True Account,

and

A Stranger in the Kingdom,

which, along with

Disappearances,

was corecipient of the New England Book Award for fiction. He lives in Vermont.