Digestive Wellness: Strengthen the Immune System and Prevent Disease Through Healthy Digestion, Fourth Edition (9 page)

Authors: Elizabeth Lipski

To gain a thorough understanding of how the digestive system works, let’s take a guided tour starting at the brain and ending at the colon.

Before you even put food into your mouth, any sound, sight, odor, taste, or texture associated with food can trigger the body to prepare for the food that will arrive. If you imagine eating a piece of pizza, you can taste the tangy sauce and creamy cheese and feel the texture of the crust. Digestive juices, saliva, enzymes, and digestive hormones begin to flow in anticipation of the food to come. As a result your body “revs up” to prepare for the work of digestion, and your heart rate and blood flow can change. (See

Chapter 10

, “The Enteric Nervous System,” for more information.)

THE DIGESTIVE PROCESS

THE DIGESTIVE PROCESS

Eating

(also called ingestion or the cephalic phase) is voluntary and begins when materials are put in the mouth. This is our portal for all nutrients to enter the body and involves the mouth, teeth, tongue, and parotid and salivary glands. Food choices are related to lifestyle, personal values, and cultural customs.

Digestion

occurs in the mouth, stomach, and small intestine and requires cooperation from the liver and pancreas. Mechanically, foods are chewed in the mouth and churned in the small and large intestine to break the foods into small pieces so that they can be fully digested. Proper levels of hydrochloric acid, bile, enzymes, and intestinal bacteria are critical for full digestive capacity.

Secretion

is ongoing. Every day the walls of the digestive tract secrete about seven quarts of water, acid, buffers, and enzymes into the lumen (inside) of the digestive tract. Secretion occurs throughout the entire digestive tract. These secretions help maintain pH levels, send water into the gut to lubricate it and keep things moving, and trigger enzymes to digest foods and facilitate the digestive process. Hydration is essential for this phase of digestion to work properly.

Mixing and propulsion

are muscular functions. Whatever we eat is squeezed through the digestive system by a rhythmic muscular contraction called peristalsis. Sets of smooth muscles throughout the digestive tract contract and relax, alternately, pushing food through the esophagus to the stomach and through the intestines. (Think of a snake swallowing a mouse.) When the food has been swallowed it is acidified, liquefied, neutralized, and homogenized until it’s broken down into usable particles. From the time you swallow, this process is involuntary and can occur even if you stand on your head. (When my son, Arthur, was seven years old, he demonstrated this by eating upside-down. Yes, the food went down—or rather, up—as usual!)

Absorption

occurs when digested food molecules are taken through the epithelial cell lining of the small intestine into the bloodstream and through the portal vein to the liver, where they are filtered. From the bloodstream they pass to the cells. Until food is absorbed, it is essentially outside the body—in a tube going through it. If the gut is inflamed, as with gluten intolerance or celiac disease, there can be malabsorption, which is typified by an inability to gain weight, lack of growth in children, anemia, and diarrhea.

Assimilation

is the process by which fuel and nutrients enter the cells. Technically this isn’t part of the digestive system, but it is the ultimate goal of the digestive process.

Elimination

is the last step. In digestion we excrete wastes by having bowel movements (defecation). These wastes are comprised of indigestible food components, waste products, bacteria, cells from the mucosal lining that are being sloughed off, and food that has not been absorbed.

The main function of the mouth is chewing and liquefying food. The salivary glands, located under the tongue, produce saliva, which softens food, begins dissolving soluble components, and helps keep the mouth and teeth clean. Saliva contains amylase, an enzyme for splitting carbohydrates, and lipase, a fat-digesting enzyme. Only a small percentage of starches are digested by the amylase in your mouth, but they continue to work for about another hour until the stomach acid inactivates the enzymes. On the other hand, the lipases become activated once reaching the stomach, beginning the process of fat digestion. Saliva also has clotting factors, helps to buffer acids, allows us to swallow, and protects our teeth, oral mucosa, and esophagus. Saliva also reabsorbs nitrates from our foods, primarily green leafy vegetables and beets. These nitrates are converted into nitrites by bacteria on our tongues, concentrating this a thousand times higher than those found in plasma. When this nitrite-rich saliva gets swallowed into acidic gastric juics, it converts into nitric oxide (NO), reducing inflammation throughout the body.

Chewing also stimulates the parotid glands, behind the ears in the jaw, to release hormones that stimulate the thymus to produce T cells, which are the core of the protective immune system.

Healthy teeth and gums are critical for proper digestion. Many people eat so fast, they barely chew their food at all and then wash it down with liquids. That means the stomach receives chunks of food instead of mush. This undermines the function of the teeth, which is to increase the surface area of the food. These people often complain of indigestion or gas. In

May All Be Fed,

John Robbins describes three men who survived in a concentration camp during World War II by chewing their food very well, while their compatriots perished. Simply by chewing food thoroughly we can enhance digestion and eliminate some problems of indigestion.

The most common problems that occur in the mouth are sores on the lips or tongue—usually canker or cold sores (herpes)—and tooth and gum problems.

The esophagus is the tube that passes from the mouth to the stomach. Here peristalsis begins to push the food along the digestive tract. Well-chewed food passes through the esophagus in about six seconds, but dry food can get stuck and take minutes to pass. At the bottom of the esophagus is a little door called the cardiac or esophageal sphincter. It separates the esophagus from the stomach, keeping stomach acid and food from coming back up. It remains closed most of the time, opening when a peristaltic wave, triggered by swallowing, relaxes the sphincter. The most common

esophageal problems are heartburn (also called gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD), hiatal hernia, Barrett’s esophagus, and eosinophilic esophagitis (EE).

The stomach is the body’s blender. It chops, dices, and liquefies as it changes food into a soupy liquid called chyme, which is the beginning of the process of protein digestion. The stomach is located under the rib cage, just under the heart.

After reaching your stomach, your food may stay in the top part of your stomach for up to an hour. Here the salivary amylase continues to break down starches. Most food stays in the stomach two to four hours—less with a low-fat meal, more with a high-fat or high-fiber meal. When the stomach has finished its job, chyme (the mixture of food mash and gastric juices) has the consistency of split-pea soup. Over several hours it passes in small amounts through the pyloric valve into the duodenum, the first 12 inches of the small intestine. Chronic stress lengthens the amount of time that food stays in the stomach, while short-term stress usually shortens the emptying time. Most of us have experienced a nervous stomach, or a feeling in the pit of the stomach, or a stomach that feels like it’s filled with rocks.

Once food enters your stomach, gentle mixing waves begin chopping up your food and increasing surface area. The hormone gastrin is also produced in the stomach and stimulates the production of gastric juices. Gastric juices are comprised of enzymes, hydrochloric acid, hormones, and intrinsic factor. For example, protein molecules are composed of chains of amino acids—up to 200 amino acids strung together. The stomach produces a hormone called pepsinogen. When pepsinogen is exposed to hydrochloric acid, it turns into pepsin, which begins protein digestion, breaking the protein you eat into short chains called peptides.

Hydrochloric acid (HCl), produced by millions of parietal cells in the stomach lining, begins to break apart these protein chains. The parietal cells use huge amounts of ATP energy to concentrate acids to the low pH of about 1 that is required by the stomach. HCl also kills microbes that come in with food, protecting us against food poisoning, parasites, and bacterial infections. The hydrochloric acid in your stomach is so strong that it would burn your skin and clothing if spilled on you. Yet, the stomach is protected by a thick coating of mucus (mucopolysaccharides), which keeps the acid from burning through the stomach lining. When the mucous layer of the stomach breaks down, HCl burns a hole in the stomach lining, causing a gastric ulcer. Hydrochloric acid production is stimulated by the presence of gastrin, acetylcholine (a neurotransmitter), or histamine. The stomach also produces small amounts of lipase, enzymes that digest fat. Most foods are digested and absorbed farther down the gastrointestinal tract, but alcohol, water, and certain salts are absorbed directly

from the stomach into the bloodstream. That’s why we feel the effects of alcohol so quickly.

Intrinsic factor is made in the stomach in the parietal cells, and it binds vitamin B

12

so that it can be readily absorbed in the intestines. Without adequate amounts of intrinsic factor, we do not utilize vitamin B

12

from our food, and pernicious anemia may occur. The main symptoms are dementia, depression, nervous system problems, muscle weakness, and fatigue. This is why many people benefit from vitamin B

12

injections, under a physician’s care, or use of sublingual B

12

or even B

12

in a nasal spray. I remember one elderly woman who had normal serum B

12

levels, but she felt enormously different when B

12

shots were added to her regimen. This simple, inexpensive therapy can dramatically affect quality of life for those who need it. By the time serum B

12

levels are low, your tissues are depleted of vitamin B

12

. A newer test to detect early B

12

deficiencies is called the methylmalonic acid test (MMA). Levels of methylmalonic acid rise when our bodies cannot transform vitamin B

12

to create energy. High levels of MMA indicate early B

12

insufficiency. Recently, researchers have remarked that probably the best test for B

12

is just taking sublingual B

12

supplements or a trial of B

12

shots to see if you feel better. I have seen this to be true; when people need B

12

and take it, their energy and sense of well-being soar. People who try B

12

and have sufficiency already don’t notice a thing.

Hydrochloric acid is also produced by the parietal cells. As the parietal cells become less efficient, the production of both hydrochloric acid and intrinsic factor falls.

The most common problems associated with the stomach are upset stomach, gastric ulcers, and underproduction of hydrochloric acid.

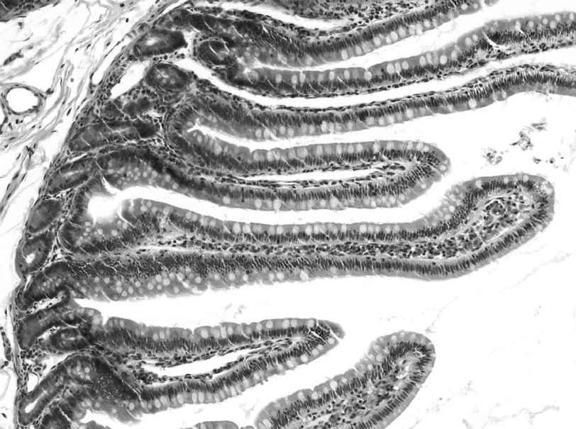

The GI mucosa, depicted in

Figure 2.2

, is the inner lining of the digestive tract. It consists of the lumen, which is the space inside the digestive tube; the epithelial layer; the lamina propria; and the muscularis mucosae, or smooth muscles. The entire mucosa is a large mucous membrane, not unlike the tissues inside of your nose. It is here that our food makes contact with us and is eventually absorbed in the intestines. It is home to trillions of bacteria and fungi and is the center of our body’s immune system. It is your body’s first line of defense against infections and other invaders.

The primary layers of the gut mucosa (also called gut-associated lymphoid tissue, or GALT) include the epithelium, the lamina propria, and the muscularis mucosae. The epithelium is comprised of a single layer of cells that come into direct contact with your food. This layer of cells is held together in tight junctions (desmosomes) that prevent leakage of molecules between the cells. (See

Chapter 4

.) This epithelial layer replaces itself every five to seven days and uses glutamine as its primary energy source. There are exocrine cells among the epithelial cells that secrete mucus and fluid as well as endocrine cells that release hormones.